By David Brule

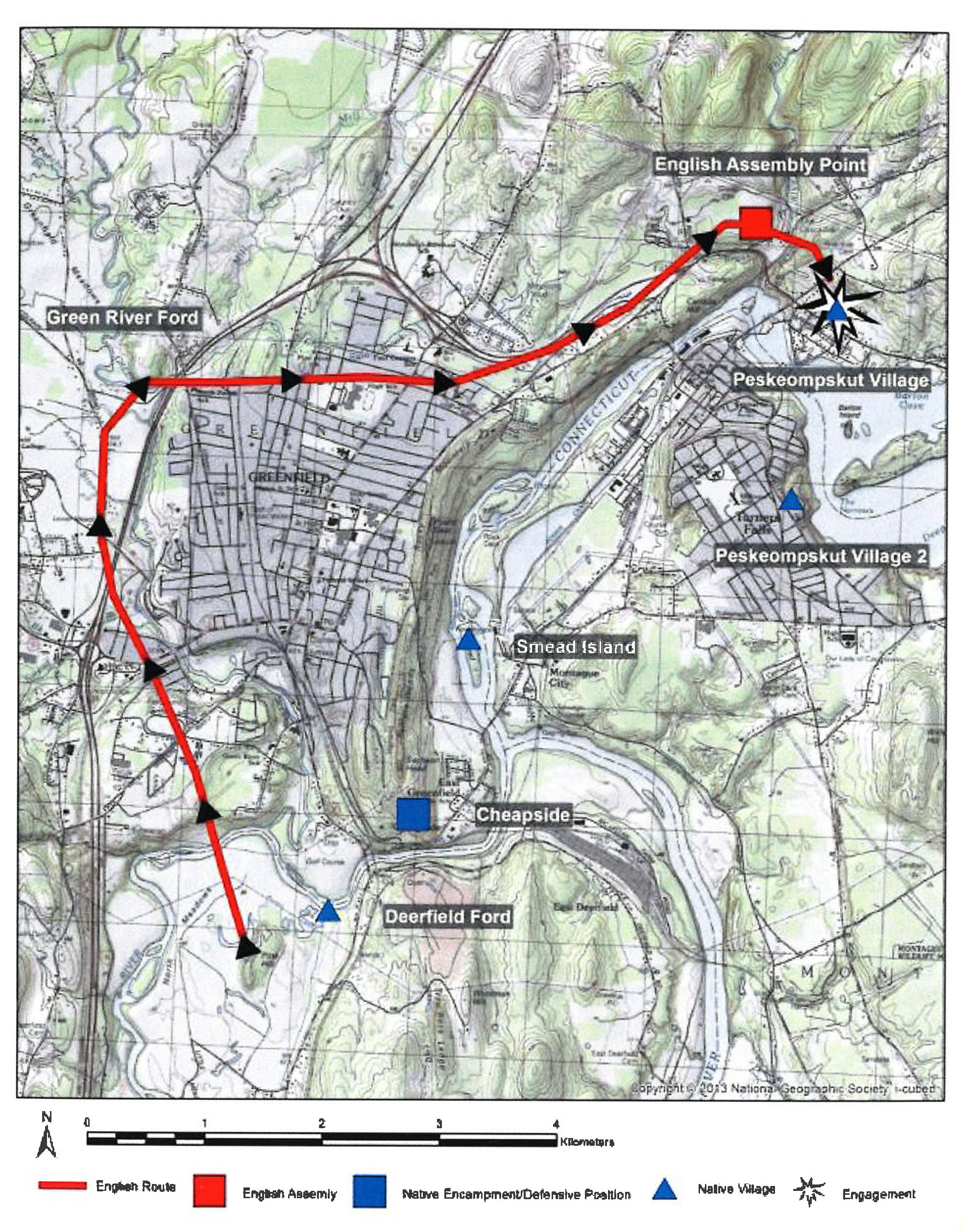

On the dark and threatening night of May 18, 1676, Captains William Turner and Samuel Holyoke set out from Hatfield and Northampton with roughly 150 men, mostly young farmers from the Connecticut River Valley.

They headed north through the burned-down town of Pocumtuck, the village now known as Deerfield. They were headed for the falls at Peskeompskut, sometimes known as Deerfield Falls. Turner, at 63, was sickly and feeble after spending 5 years in a Puritan prison for being a Baptist. He had asked to be relieved of this command. Massachusetts Bay Colony refused. He didn’t know, but likely suspected, that he was to meet his destiny the following day.

Meanwhile, a thousand or more Indigenous people from the allied nations of Pocumtuck, Nipmuck, Abenaki, Quabaug, Nashaway, Norwottock, Narrangansett , Wampanog and others had gathered at the falls. This was a traditional, 10,000-year-old fishing falls, a sanctuary where Native peoples could regroup, restore, and replenish, and in this context, decide on matters of peace or war.

King Philip’s War, often called Metacomet’s Rebellion, was set in motion on June 20, 1675, when members of the Pokanoket Wampanoag looted several homes in Swansea, likely without Metacomet’s knowledge. Shots were exchanged between Natives and settlers, and the powder keg was touched off.

The war engulfed all of New England in brutal conflict. Both sides were beaten and bloodied by the spring of 1676.

The United Colonies composed of Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth, the Connecticut colonies of Hartford and New Haven, plus Roger Williams’s settlement in Rhode Island faced a powerful coalition of Narragansett, Wampanoag, and Nipmuck, plus the Connecticut River Tribes of Pocumtuck, Norwottock, Nonotuck, and Agawam.

By war’s end, more than 52 settlements had been attacked and some burned to the ground including Deerfield, Northfield, Springfield, and Providence.

The May 18-19 expedition of Turner and his dragoons is said to have been triggered by a cattle raid involving Native soldiers from the Peskeompskut camp. The loss of more than 70 cattle enraged the settler-farmers of the Valley, and they set out on a raid of revenge. They had witnessed family and friends being killed in raids that had destroyed numerous towns mentioned above.

Settlers had pursued and driven the Natives from their own homelands along the coast and in the interior around Mt. Wachusett and beyond. They were devastated by famine, disease, the loss of traditional leadership, the burgeoning English population, and relentless attacks.

The day of May 19, 1676, was going to end badly for all sides.

Avoiding the armed camps of the Native coalition, Turner fell on the non-combatant camp at Peskeompskut, killing as many women, children, and elderly as they could in the dawn raid of May 19.

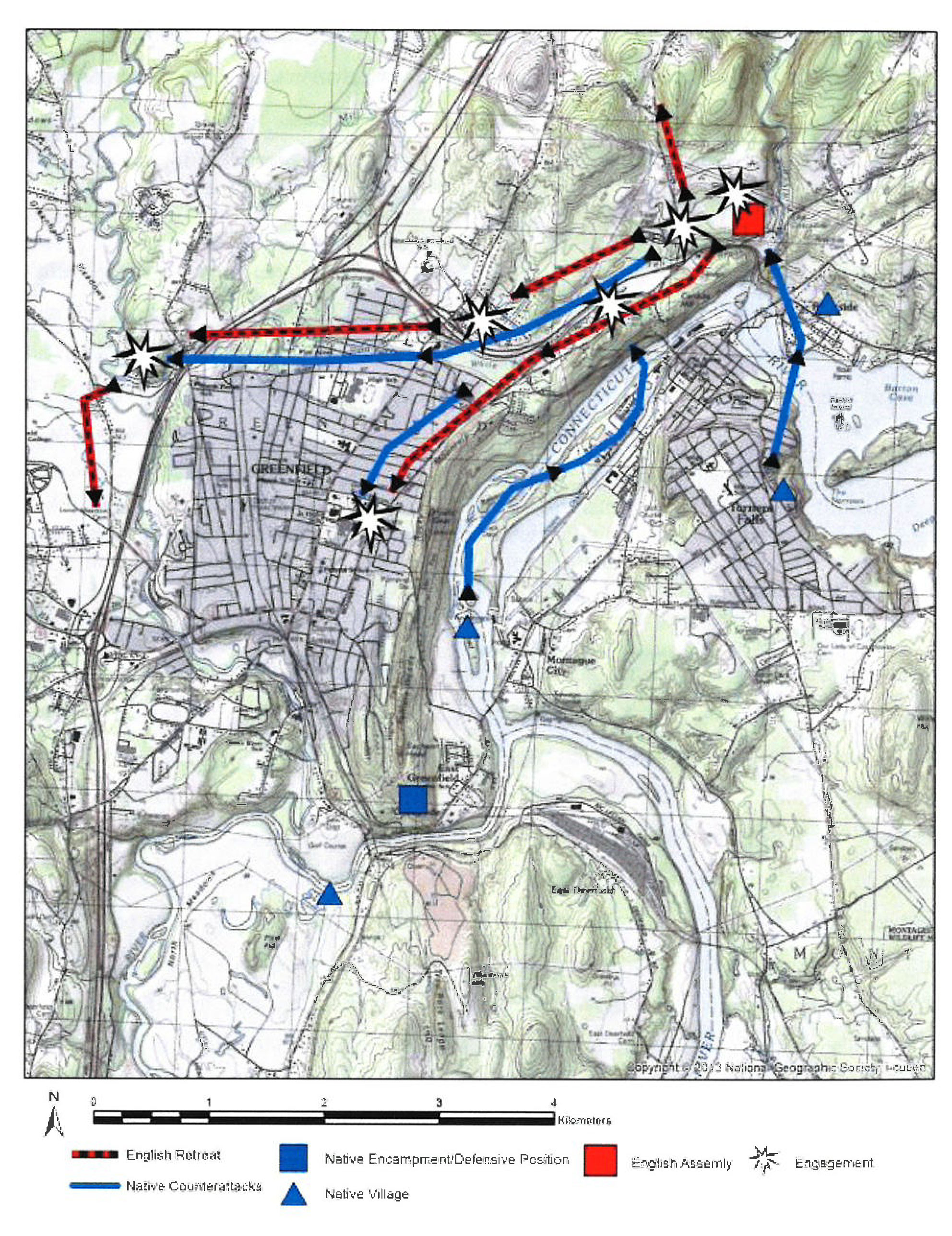

When the noise of the attack reached the Native soldiers’ camps on the south bank of the falls, the camps on the river islands, and at Wissatinnewag, they rushed to the scene and routed the English attackers who had lingered too long there, plundering and looting.

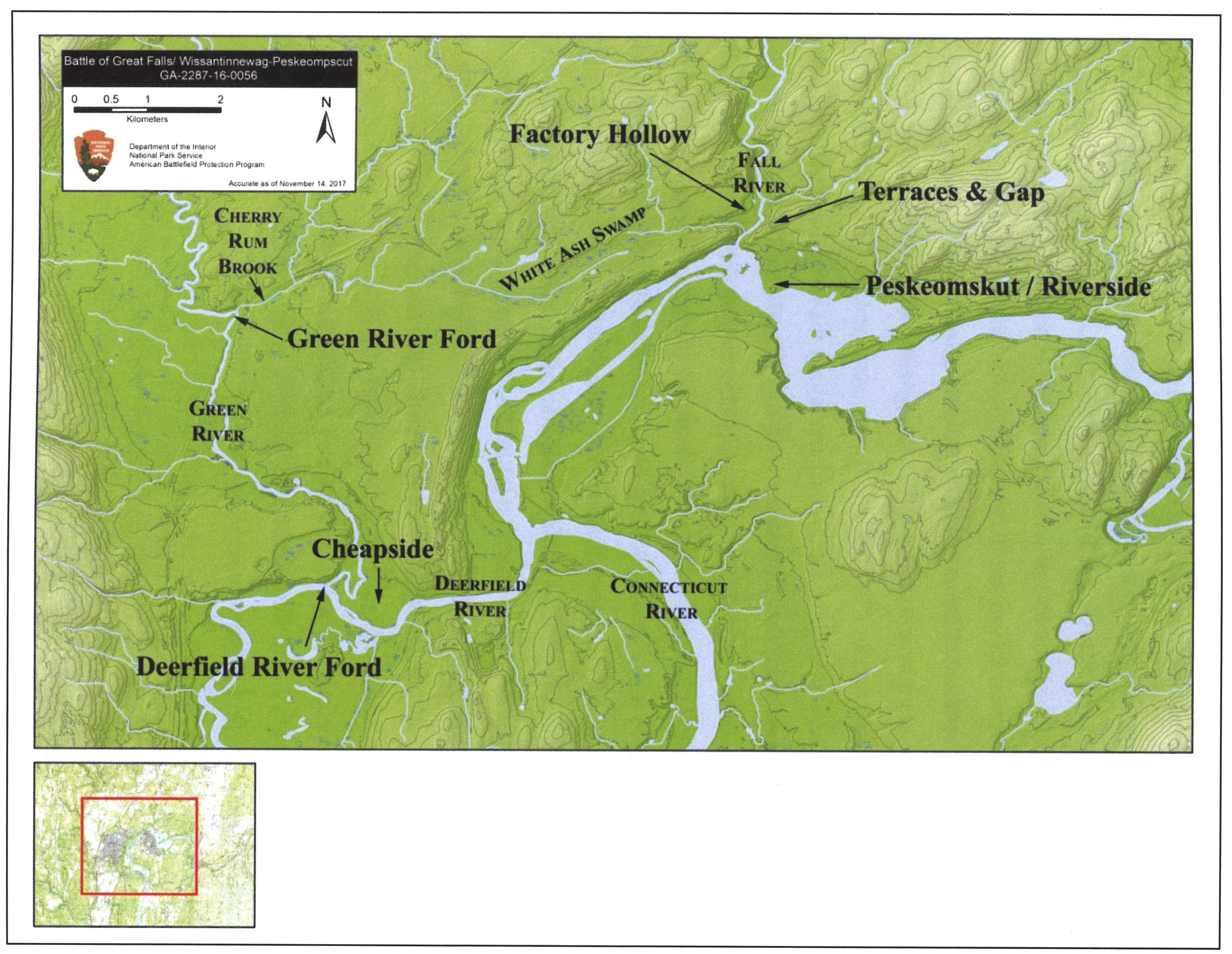

A panicked retreat ensued with the colonials fleeing back the way they came. The inter-national tribal forces, knowing the terrain, waited in ambush all along the retreat route through White Ash Swamp, along Cherry Rum Brook, to the Green River ford, down to the Deerfield River, and into the north meadows.

It was an English disaster: close to 50 men were killed in the retreat, including Captain Turner. Many more later died of wounds and battle-related trauma, including acute alcoholism and suicide.

Close to 300 Natives were killed at the falls, and many more Native soldiers were killed in their counter- attack in this demoralizing loss. The war was to end a few months later, by August, with the death of Philip, the capture and execution of most of the Native coalition leaders, and the shipment of many survivors into slavery in the West Indies.

The victors wrote the histories, but what really happened?

Funded by a National Park Service Battlefield Protection Program grant, a 2014 coalition of five Historical Commissions from the modern-day towns of Montague, Deerfield, Greenfield, Gill, and Northfield, plus Tribal Historical Preservation Officers from the Nipmuck, Abenaki, Narragansett, and Wampanoag began meeting monthly to study the tragic event. The intent was to trace the approach and retreat routes of the colonial force as well as the Native coalition strategies in hopes of teasing out the true nature of the event, using modern-day technical archaeological tools. This study has been on-going. The results have proven to provide a new, balanced perspective on the events of that day in May, 1676.

The National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program Documentation Project for the Battle of Great Falls/ Wissatinnewag-Peskeompskut is now in its 10th year into this little-known yet tragic event.

Dr. Kevin McBride and Dr. David Naumec were contracted by the Town of Montague, as grant recipient for the study. This archaeological team has developed research and field reports conducted on the seven-mile stretch of the running battle of that fateful day of May 19, 1676.

Collaborating with a team of skilled metal detectorists and using state-of-the art military terrain analysis, which of course were not available to 19th-century historians who wrote second-or third -hand accounts, we have gotten closer to a clearer interpretation of the events of that day. In addition, Tribal authorities have accompanied the archaeologists working in the field.

The growing documentation of this research involves tracing the approach and retreat routes taken by the colonials. Successfully tracking the retreat route has been a key element in piecing together the story of that day. In addition, the military terrain analysis protocols have helped identify choke points and ambush sites that earlier historians barely mention, if at all. More than 900 artifacts, mostly musketballs, have been recovered as of September 2024, and reveal some here-to-fore undocumented intense fighting.

In addition, more has been learned about Native strategies with the assistance of the four Tribal Historical Protection Officers. The names of the Native coalition leaders have been recovered and should form an important part of the new histories being written about this war.

A key component has been the recovery of the notebooks of Stephen Williams, the celebrated “Boy Captive of Old Deerfield”. Williams interviewed a number of the surviving veterans of that battle, both colonial and Indigenous combatants. The notebook is a recent acquisition of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library, and the interviews were transcribed by Deerfield’s Dr. Peter Thomas. These first-hand accounts proved quite valuable in piecing the story together.

This September, the team has documented new evidence of significant fighting at the site of the ford across the Deerfield River and into the North Meadows. The preliminary analysis suggests the area of Meridian Street and Colorado Avenue in Greenfield was the site of the heaviest fighting of the entire running 7-mile battle. More than 300 musket balls have been recovered from this one site alone.

McBride and Naumec suggest that there are indications that after the death of Captain Turner, the remainder of the English forces now under the second-in-command Captain Holyoke, may well have had to fight their way through the heavily armed Native coalition in order to get across the Deerfield River. They faced an ambush in this spot overlooking the ford while another group of Native coalition forces attacked the English from the rear.

Meridian Street would have been the site of more prolonged stationary fighting as compared to the other areas of the battlefield.

More field work is planned to try to reach some summary conclusions. Recent work in the North Meadows has indicated further fighting there until the English were in sight of the abandoned village of Deerfield itself.

The true nature of this event is being coaxed out through the evidence gathered so far, including the development of previously unexplored scenarios, not recounted by early historian George Sheldon and others.

This massacre of Native non-combatants and the ensuing counterattack by the Native coalition could well have shaped the next 100 years of strife for Deerfield and the New England settlements writ large.

This King Philip’s War certainly saw a sequel little more than 20 years later, with the devasting attack on Deerfield in 1704.

David Brule is a local author and has been a guide at Historic Deerfield since 2013.

He is project coordinator of the ongoing (2014-present) National Park Service grant-funded study of the events that took place in the central Connecticut River Valley during King Philip’s War of 1675-76 with a focus on the massacre and counter-attack at the Falls Fight of May 1676. David is also president of the Nolumbeka Project, Inc, and chairman of the Nehantic Tribal Council.