by David Bosse

To book readers, encountering a photo of the author on the cover or the jacket flap is a common occurrence. An image helps satisfy our curiosity about a newly encountered writer or reassures us about an old favorite. An author’s visage helps make some connection with prospective readers, and a photogenic author may even help sell copies of the book. Depicting a book’s author has a long history; the first printed book to include a portrait appeared in Milan, Italy in 1479. [1]

The impetus for including a likeness could come from either the author or the printer/publisher. In a poem accompanying the illustrated title page of The Anatomy of Melancholy, author Robert Burton (1577–1640) comments on the practice of portraiture and accounts for the initial use of his image in the book’s third edition (Oxford, 1628):

Now last of all to fill a place,

Presented is the Author’s face…

His mind no art can well express,

That by his writings you may guess.

It was not pride, nor yet vainglory

(Though others do it commonly),

Made him do this; if you must know,

The printer would needs have it so.

In a way, this clever explanation encapsulates the principle of physiognomy, a belief dating back to the ancient Greeks and still popular during William Salmon’s time. Adherents believed that character could be inferred from physical features—the antithesis of the inability to judge a book by its cover. [2] The presence of a frontispiece portrait put the author’s image and the book’s text (his mind) in conversation for the reader to judge.

In 2008, the Historic Deerfield Library acquired a remarkable collection of books and pamphlets on applied color and color theory from the estate of Stephen L. Wolf. Gathered over a period of more than 50 years, his extensive library contained many craft manuals that discuss receipts (i.e., recipes) and techniques. Among these, the works of William Salmon provide a window on author portraiture in books printed during the long eighteenth century.

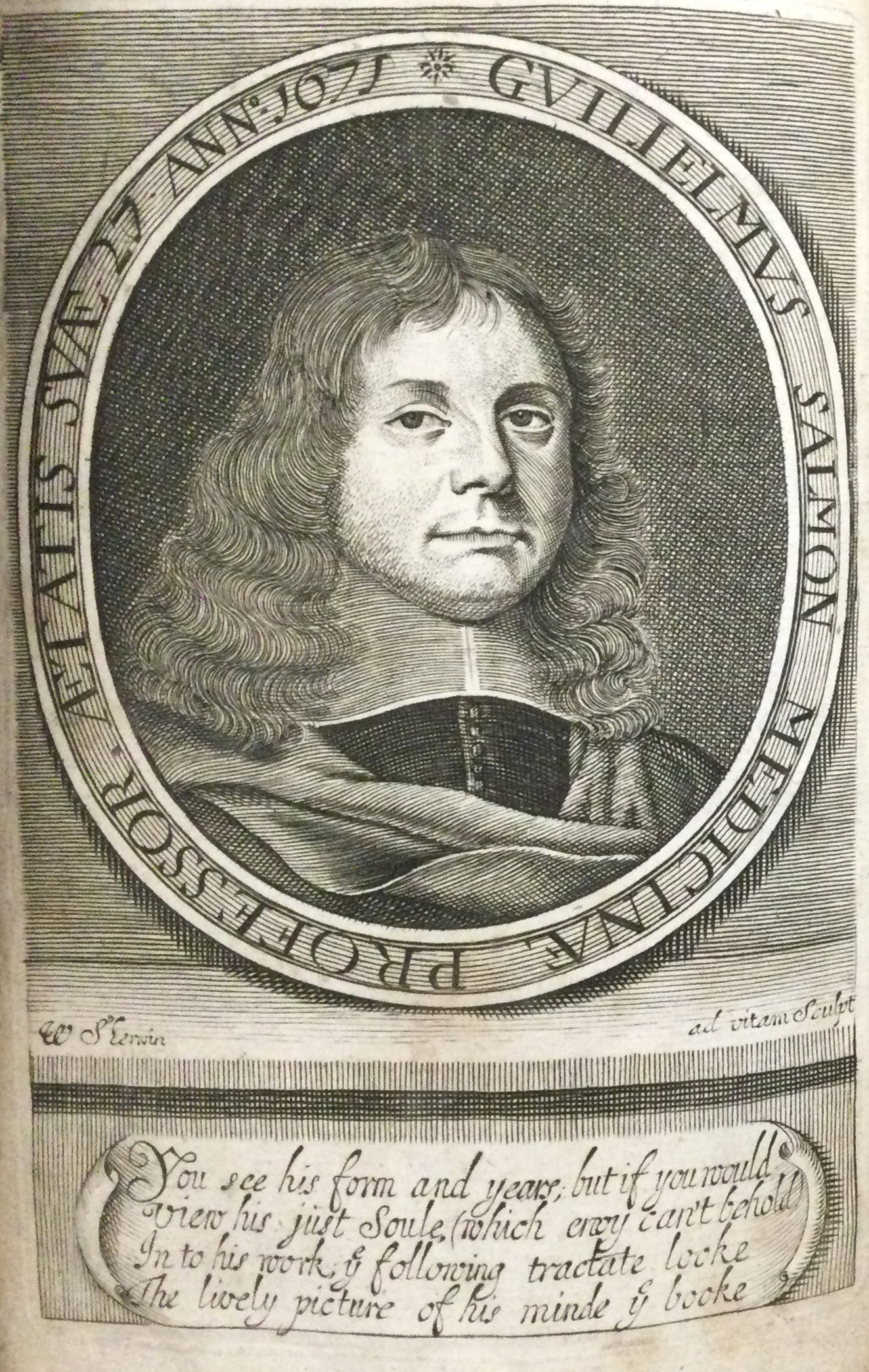

The earliest printed portrait of William Salmon (1644–1713) titled him professor of medicine . Some contemporaries and modern commentators regarded him as a quack or charlatan instead. [3] Salmon’s resume in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography claims that his training with a “mountebank,” included performing slight-of-hand tricks and learning to compound curatives and panaceas. Whatever the basis of his medical instruction, Salmon claimed extensive knowledge of “Physick” in his first book, Synopsis Medicinae, or a Compendium of Astrological, Galenical and Chymical Physick. [4] Printed in London in 1671, the Synopsis featured a frontispiece portrait of the author engraved by William Sherwin (c. 1645–1709). (Figure 1) In the portrait’s oval surround, the author is introduced: GVILIELMVS SALMON MEDICINAE PROFESSOR. AETATIS SVAE 27 ANN: 1671. [5] Below Salmon’s image a pair of couplets advise the reader that:

You see his form and years, but if you would

View his just Soule, (which envy can’t behold)

In to his work, ye following tractate looke

The lively picture of his minde ye booke

Here we are again reminded that beyond judging what the author’s features reveal, the reader need also assess the writer’s mind as expressed in “ye booke.”

This portrait of the young author with open countenance and modest dress would see use again and again in Salmon’s second and most successful book, Polygraphicae: Or, the Arts of Drawing, Engraving, Etching, Limning, Painting, Varnishing, Japaning, Gilding, &c. The book remained a steady seller for the next 30 years, going through five revisions and eight editions. At the time of the book’s final printing, the author claimed that more than 15,000 copies of Polygraphice had sold. With each new printing Salmon revised existing chapters and added new ones on alchemy, dyeing and staining, adulterating precious stones, and cosmetics.

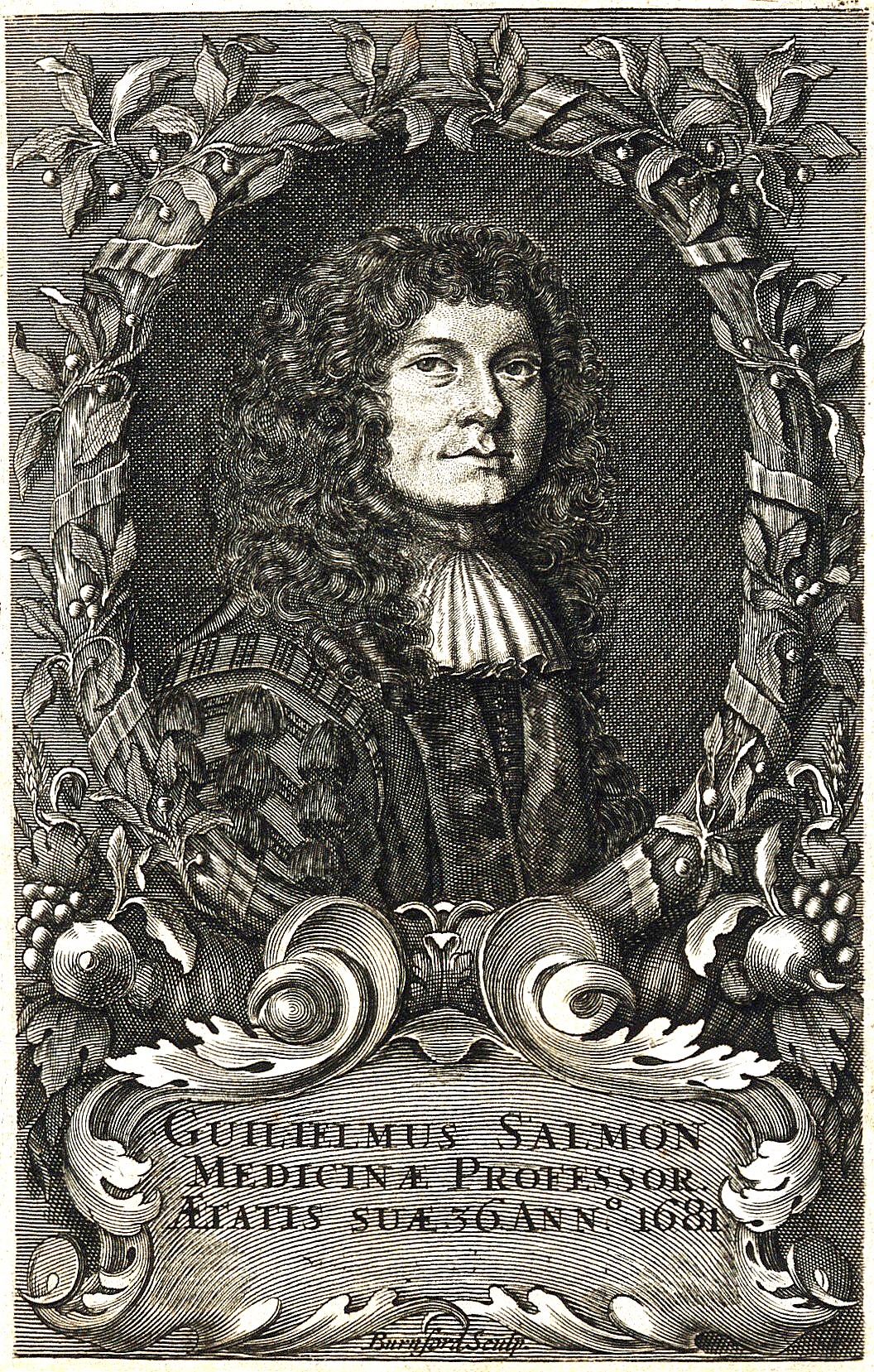

Salmon continued to churn out publications on medicine, anatomy, applied arts, pharmacology, botany, household receipts, and even five years of an almanac. Most of these publications reused material of his own creation or freely borrowed from others. Exhaustive compilation of information, condensed and simplified, formed the basis of his works, many of which included the author’s portrait. (Figure 2) We next encounter an image of an older, more affluent man, engraved by Leonhard Burnford (1645–1703), in Systema Medicinae, a Compleat System of Physick Theorical and Practical (London, 1681). A full-bottom (below the shoulders) wig and lace cravat add to his gentlemanly presence. Bernhard’s naturalistic Baroque surround of plants and fruit forms a distinct and solitary departure from the architectural elements other portraits of Salmon employ as framing.

The face that looked out at readers of the second edition of Systema Medicinae appears serious, even stern. (Figure 3) Was Salmon’s demeanor intended to project the gravity expected of one dispensing medical advice? One imagines that few readers found the portrait comforting. A few years later Frederick Hendrick van Hove (c. 1628–1698) produced a different portrait of a mature, more relaxed, Salmon, based on a 1687 portrait engraved by Robert White (1645–1703). [6] (Figure 4) Ichabod Dawks, noted by the initial “J” which at that time was often used interchangeably with a capital I, apparently commissioned the portrait for the book. His father, Thomas Dawks, Jr., owned full or partial copyright to several of Salmon’s works, including Systema Medicinae which passed to Ichabod in 1689. [7]

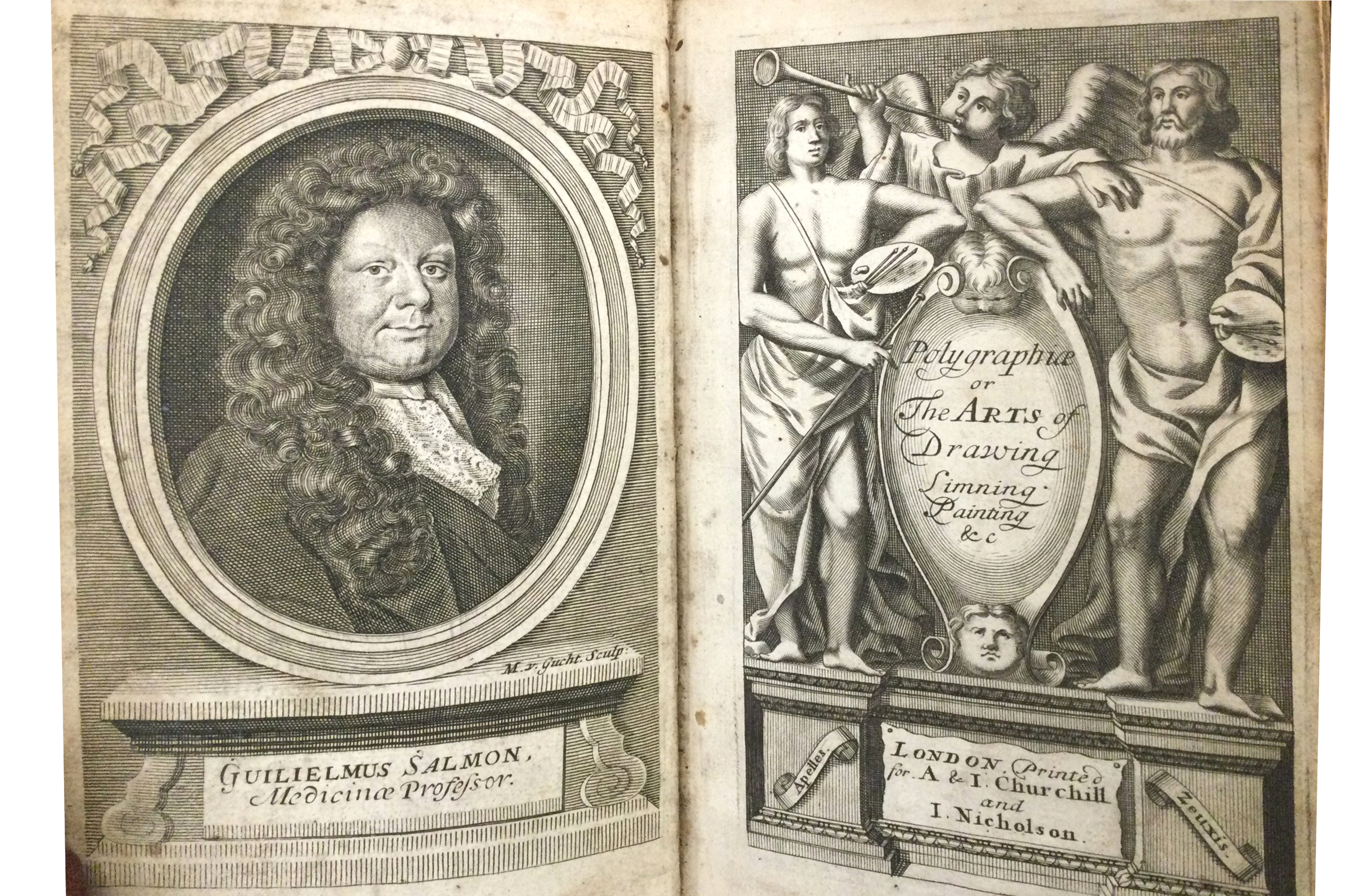

The final edition of Polygraphice appeared in 1701 with a frontispiece by Michel van Gucht. (Figure 5) As in other editions the engraved title page depicts two male figures: Zeuxis, a fifth century BCE painter, and Apelles, a fourth century BCE painter holding palettes and paint brushes. Here a hint of satisfaction plays upon the features of the older, financially secure author. Substantial sales of his books, and even his remedies advertised therein, made Salmon a considerable fortune. The various frontispiece portraits of Salmon helped shape his public persona during his passage from accused charlatan to gentleman. With the exception of William Sherwin’s engraving, each of the portraits bears a general similarity, most likely due to the influence of previous versions. For Salmon and his publishers, Robert Burton’s earlier protestation against pictorial vainglory held no merit.

Commenting on portraiture in An Essay on the Theory of Painting (London, 1715), Jonathan Richardson believed that striking a balance between pictorial truthfulness and representation of character was essential. Richardson held that a good portrait would show “whether the Person is Grave, or Gay; a Man of Business, or Wit; Plain, &c.” With no known painting of Salmon in a public collection, we are left with these small images, engraved by several different hands over a period of decades, to gauge the effectiveness of William Salmon’s iconography.

NOTES

[1] Elizabeth Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Communications and Cultural Transformations in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1979), 176.

[2] As early as 1708, the compiler of a collection of Aesop’s fables, Truth in Fiction, or Morality in Masquerade, commented that “Man is not to be judg’d by his Out-side any more than a Book by its Title-Page…” in contradiction to the earlier conviction.

[3] In her 2013 PhD. dissertation (University of York) “The Art Lover as Cultural Entrepreneur: Aspiration, Self-Fashioning and Social Mobility in William Salmon’s Polygraphice,” Caroline Good reviews the sources that question Salmon’s medical knowledge.

[4] Dr. Thomas Williams (1718-1775) of Deerfield, MA, owned a copy of Salmon’s work, notes from which are in his papers in the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library.

[5] “William Salmon Professor of Medicine. In the 27th year of his age. Year of the Lord 1671.”

[6] White’s version includes a coat of arms, but not that associated with the Salmon surname. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw90920.

[7] Keith Maslen, “Puritan Printers in London; The Dawks Family 1627-1737,” Bibliographical Society of Australia & New Zealand Bulletin Vol. 25, Nos. 1&2 (2001): 97-98; 103-4.