By Ella McDaniel, Museum Education and Interpretation Intern

As we crawl to the end of yet another record-setting summer of heat and humidity here in Massachusetts, the unbearably high temperatures bring to mind questions about the best ways to deal with summer weather. In the context of our museum, we might ask how people in late 18th-century America endured the heat. What does it mean, now and centuries ago, to “keep cool” in the summertime? Could practical concerns be more important than coolness?

For my summer project as an intern with the Historic Deerfield Museum Education department, I set out to investigate this issue. When days get steamy, many of us in the modern era have a set routine. We may turn our air conditioning units to maximum cold, go swimming, or wear the lightest amount of clothing possible while still being acceptable. However, these techniques were either impossible or inappropriate in the late 1700s. Does this mean that people suffered through their farm work under many layers of fabric?

In rural villages like Deerfield, Massachusetts, where much of the day was spent employed in agricultural work, staying out of the heat was not an option. Neither was wearing a super short gown or open-toed shoes. This was not only because of differing fashion norms of the period but also practicality. Thorns snagging on one’s stockings, for instance, is much better than having them scrape skin, and in a time before sunscreen, pinning a kerchief around the neck prevented sunburn. How well people’s clothing protected them in a working environment was often more important than feeling comfortable.

However, this does not mean that people in the 18th century paid little attention to how clothes felt on their bodies. Just like today, different fabrics accomplished different goals. While synthetic textiles did not yet exist, early Americans had good choices. Linen and wool were more affordable than cotton and silk, which were imported from Asia, and both wool and linen provided breathability and moisture wicking on a hot summer’s day. [1]

Both men’s and women’s ensembles included garments that maximized protection from the elements and kept the wearer cool. For instance, shirts and shifts were undergarments made from linen, a fabric that is washable and lightweight while also limiting sun exposure. Wool, while a surprising choice for the summertime, is water-resistant and flame-retardant, making it good for outer clothing when working in damp conditions or near a fire. [2] Early New Englanders could mix textiles to create an outfit that suited the needs of the season.

Exploring Natural Fibers with Visitors

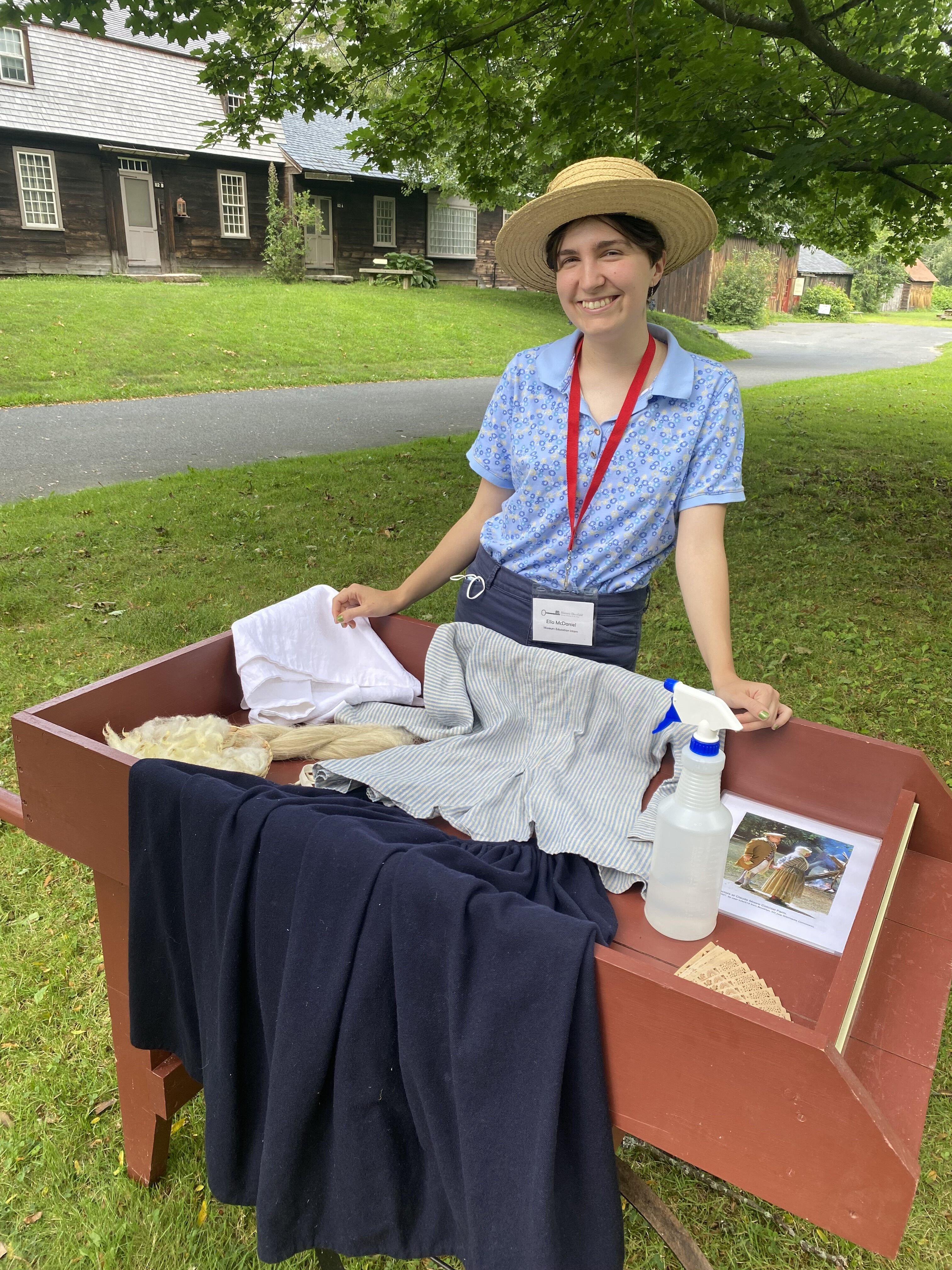

Now, it’s one thing to study these properties on the page, but for a deeper understanding of how textiles support our bodies in the summer, we need to feel them. With this in mind, I developed a Creative Encounters Cart called “Keeping Your Cool: Wool and Linen in Late 18th-Century Clothing.” Parked outside along Old Main Street in Deerfield, visitors could stop by the cart for a minute to get their hands on samples of the fibers and perform tests of the different properties. By exploring this process in a tactile way, people could better understand what wearing these garments in the summer might have felt like and why people in the late 18th century preferred certain fabrics.

The three fiber property tests I had visitors explore are insulation, moisture wicking, and breathability. The first step in the encounter involved feeling the fabrics. I asked visitors to:

The three fiber property tests I had visitors explore are insulation, moisture wicking, and breathability. The first step in the encounter involved feeling the fabrics. I asked visitors to:

Touch the woolen petticoat that’s right in front of you. Put your hand under it. Can you feel how hot and stifling the fabric is? Now try that with the linen. Still warm, but not nearly as unbearable. That is the insulating power of wool – great for the winter or a thick apron, but you might opt for a linen petticoat instead.

Afterwards, I asked visitors to consider the breathability of the fabric:

Next, let’s compare just how airy the fabrics are. We can know that wool has the ability to absorb water and release it as vapor. We can read that linen’s long, straight fibers allow for more space between skin and fabric. [3] But when we hold our hand behind a length of cloth and have a friend fan a breeze through the other side, we learn that both wool and linen are quite breathable.

Finally, the water test. This was the most fun for visitors to explore. From running their hands through the oily raw wool to seeing the water bead up on the surface of the wool fabric without seeping through, it is a full-circle scientific moment. Using a spray bottle is just fun, too.

Overall, the take-away from this encounter is that people in 18th-century rural New England were able to make decisions about their summer clothing that responded to the needs and restrictions of the season. These decisions reflected the real impacts of wool and linen on their bodies, including the heat and perspiration they would endure. As we continue to face higher temperatures and weather extremes due to climate change, we might want to lean into the inherent benefits of natural fibers. Keeping our cool as we deal with the heat is no small feat, but taking lessons from a pre-synthetic world might help us do just that.

[1] Stowell, L. 2021, June 14. Fabrics for the 18th Century and Beyond. American Duchess Blog. https://blog.americanduchess.com/2021/06/fabrics-for-the-18th-century-and-beyond.html.

[2] Oubas Knitwear. 2023, August 16. Wool Wonders: The Science Behind How Wool Keeps Us Warm and Cool. https://www.oubasknitwear.co.uk/blogs/news/wool-wonders-the-science-behind-how-wool-keeps-us-warm-and-cool.

[3] Satenstein, L. 2017, July 27. Science Says Linen Is the Coolest Summer Fabric—But Can It Look Cool? Vogue. https://www.vogue.com/article/chic-linen-shirts-for-summer.