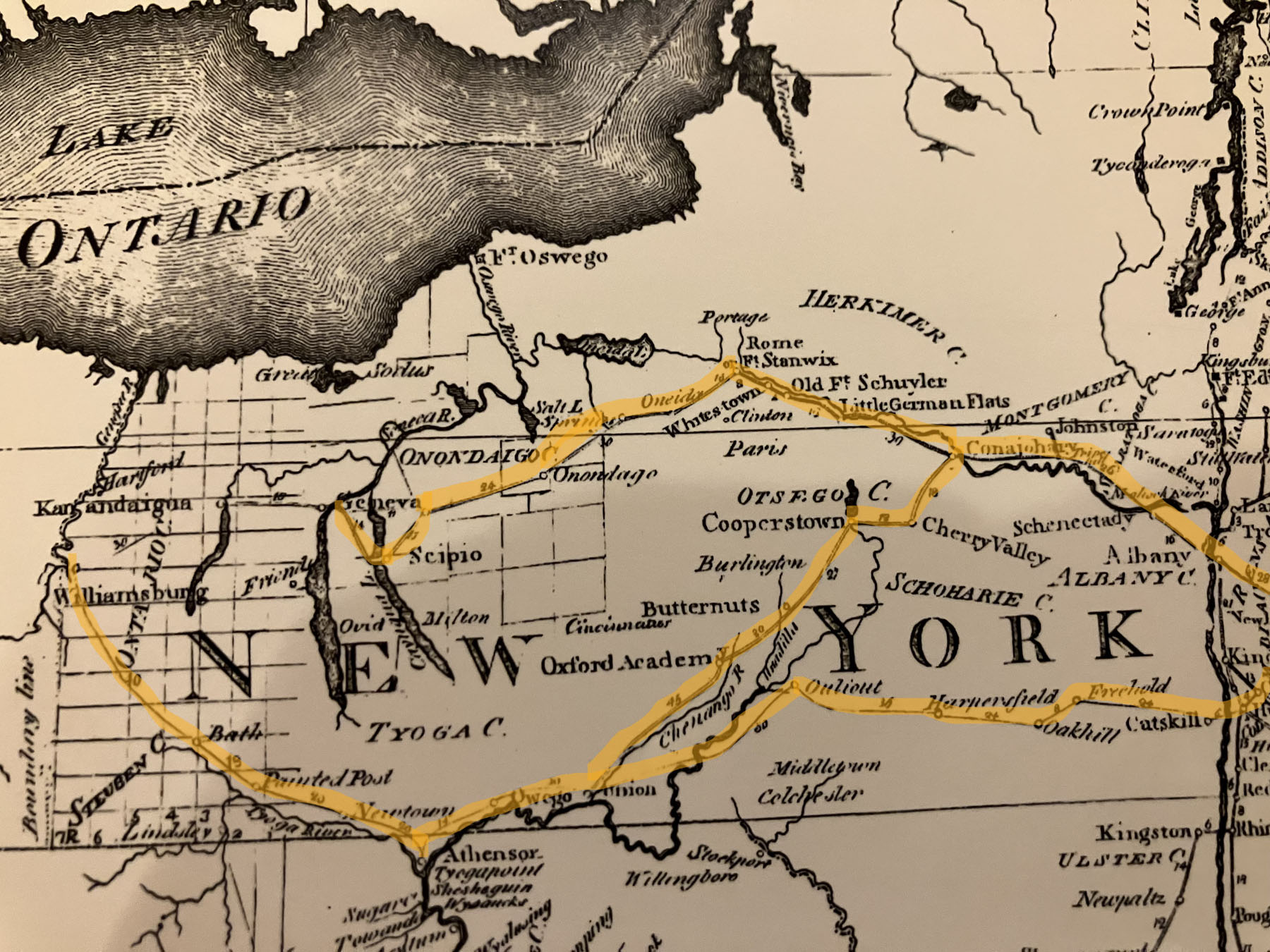

Close-up of 1796 postal route map highlighting new postal routes to western New York.

by Harry Sharbaugh, Senior Guide and Heather Harrington, Associate Librarian

In 1805, after eight years as a Deerfield tavernkeeper, Erastus Barnard, his wife Sally, and their three small children moved to Canandaigua, New York. What prompted this long-distance move and how did he gain enough confidence to do this? The answers lie in the flow of information to and from the Connecticut River Valley via personal communications and letters and newspapers through the new United States Postal System.

Canandaigua is the namesake town of one of the finger lakes of western New York. This area was the long-time home of the Seneca Nation, one of the five tribes of the Iroquois. During the Revolutionary War, the majority of the Iroquois sided with the British, with the exception of the Oneidas. The British encouraged their Native allies to attack and raid the settlers of central and western New York to aid their war efforts. As a result, the Continental Congress authorized General John Sullivan to lead an expedition through central and western New York to neutralize the threat. After the war ended, Great Britain ceded the land to the United States. The U.S. promptly opened settlement in the area often referred to as the Genesee. Some of the earliest settlers to the area were actually former soldiers of Sullivan’s Expedition.

The town of Canandaigua was part of this large area opened for settlement. Land speculators purchased large tracts and broke them into smaller parcels for resale. These included New Englanders Nathaniel Gorham and Oliver Phelps, who targeted fellow New Englanders for resale. Nuclear “city-towns” were established to attract settlers. Such towns included Canandaigua, Phelps, and Geneva. Canandaigua settlement began in 1789 and by 1800 the town was an established community with a central square, main street, seventy households, forty businesses, and a steepled church. [1]

Information about this area came to Deerfield via travelers, newspapers, and letters. In 1792 a Postal Act was passed, championed by George Washington. The Act created over thirty new postal routes with one of these new routes extending westward from Albany to Canajoharie, which was extended in 1794 to Canandaigua. A new postal route from Springfield, Massachusetts, to Hanover, New Hampshire, was also created with a post office in Greenfield, Massachusetts. Deerfield would get a post office in 1800 with Ebenezer Barnard, brother of Erastus, one of the earliest postmasters. Barnard Tavern was also the post office for at least a year and possibly more. Now regular mail was possible, instead of relying on infrequent encounters with travelers. Prior to this, there was an informal practice of privately carrying mail, which if not personally delivered, was often left at the local tavern for pick-up. This informal practice persisted well into the 1800s and overlapped with the coming of the postal system. Newspapers were also delivered to the tavern for direct reading and discussion, all overheard by Erastus Barnard, tavernkeeper. Barnard also oversaw dinner and other conversations while serving a meal or drinks. Hence, he was at the epicenter of information flow into Deerfield.

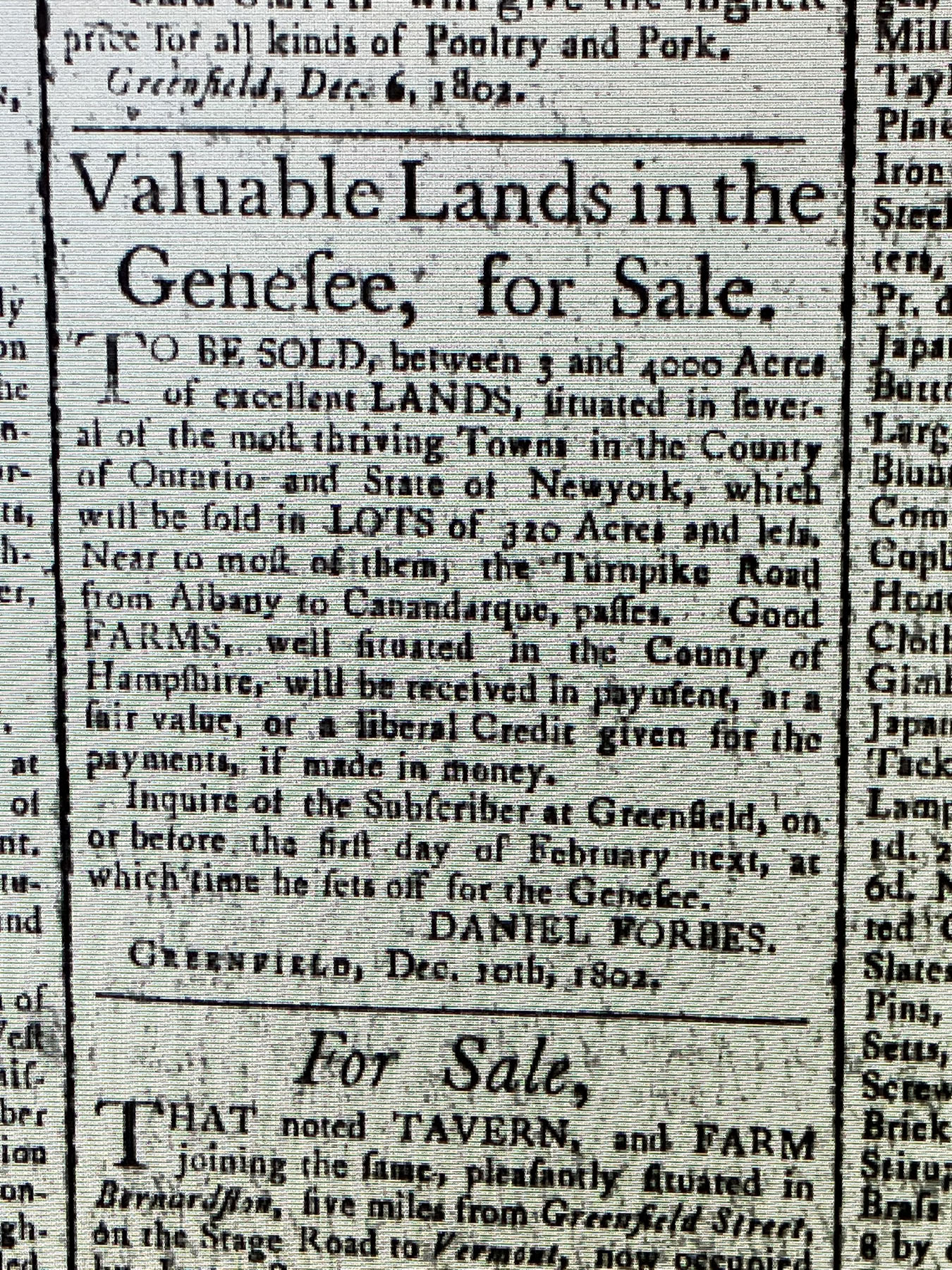

In November 1794 a treaty was signed at Canandaigua formalizing the opening of the extensive lands. This new treaty was printed in its entirety in the Greenfield Gazette in February 1795. In 1802 the paper advertised land for sale in the Genesee area.

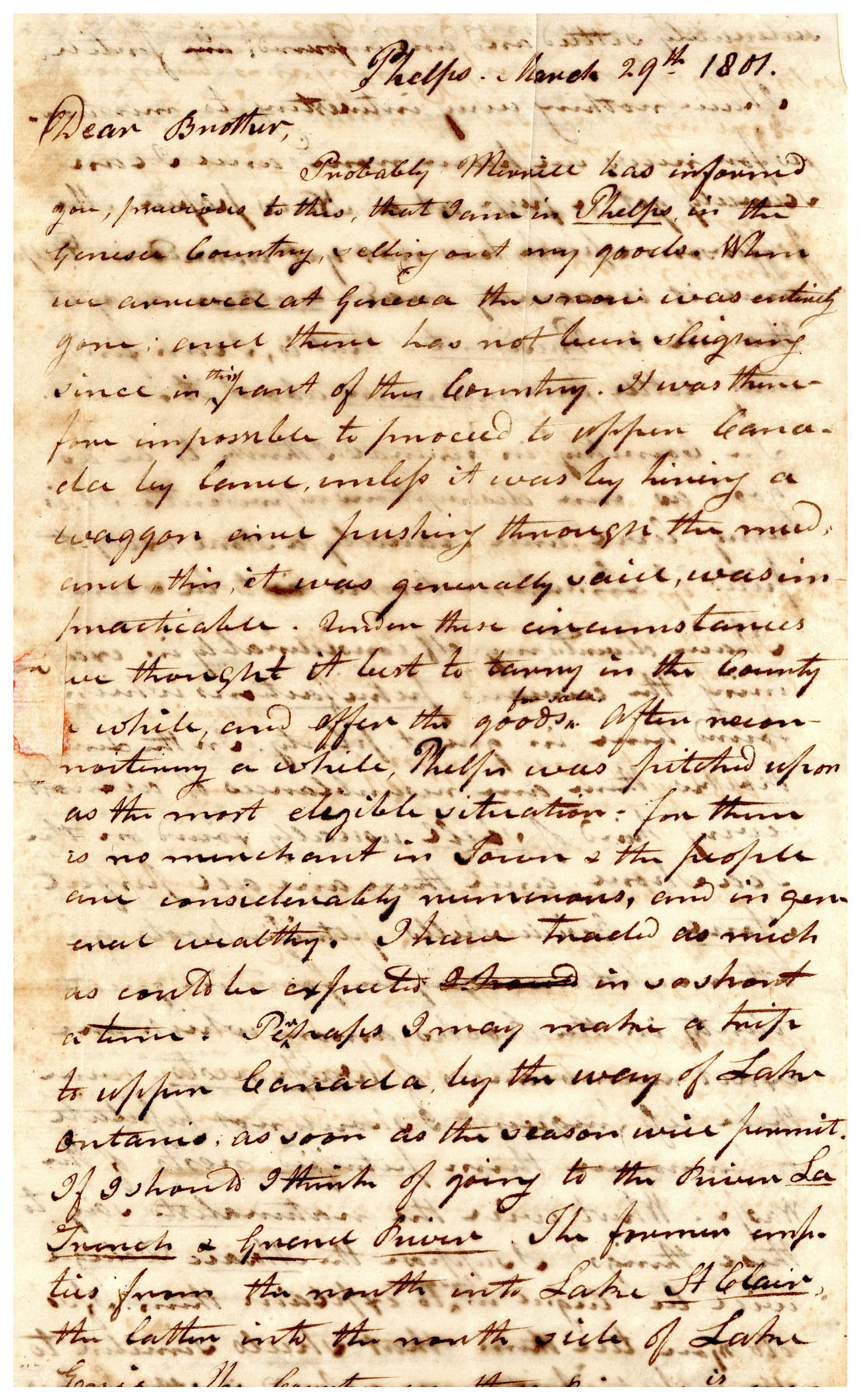

Additionally, Barnard must have been aware of other local residents who had moved to or traveled to the Genesee area. Epaphras Hoyt, a long-time Deerfield resident, went to Phelps in 1801 to begin a general store business. While there he wrote letters home to his brother Elihu and his wife Experience. He also kept a journal of his travels. In one letter to his brother he remarked, “the country in general I think to be as good as our descriptions represents. It is very level, and scarcely a stone except piles of limestone rocks, to be seen.” [2] He later pointed out that the land was great for growing wheat and other grain crops. [3] Hoyt also mentioned that others from the Connecticut River Valley settled there, including Erastus Stebbins of Conway and William Stevens of Colrain. Hoyt noted that he discovered that he was nominated for Register of Deeds while in the Genesee country from reading the Northampton paper. [4] This shows that the mail routes were essential in keeping the Genesee country in contact with the Connecticut River Valley. At just one cent per paper, newspapers were a large proportion of the mail.

Erastus Barnard would have seen the newspaper advertisements about cheap available land and would have heard about or known people who had lived there. He would likely have heard about the flat, level land from Epaphras Hoyt. He would know how easy it was to communicate back and forth with the area. The Genesee country would have sounded very appealing to a man living in increasingly cramped quarters with a very young family and a job that was basically a 24/7 occupation. He was probably tired of dealing with the problems of running a tavern and dealing with the public and thought it was a good opportunity to start over. In 1805 he took the bait and moved to New York State. With this departure, the Barnard Tavern, which had been kept by the Barnards for ten years, 1795-1805, closed forever.

Once reaching New York State the Barnard family lived in Phelps and then Farmington, a community founded by Berkshire County Quakers. After several years Erastus, Sally, and their growing family made their final move and settled in Canandaigua. There they raised a family of eight children and spent the remainder of their lives. While never to return to Deerfield, the Barnards maintained contact with family members in western Massachusetts through letter writing and reading newspapers, including the Greenfield newspaper which was available in Canandaigua shortly after 1810.

[1] Milton M. Klein, ed. The Empire State: A History of New York (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 266.

[2] Epaphras Hoyt to Elihu Hoyt, 29 March 1801. Hoyt Family Papers, Box 4, Folder 1, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial

Association Library.

[3] Sketch-book No. 8, Hoyt Family Papers, Box 2, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library.

[4] Epaphras Hoyt to Elihu Hoyt, 29 March 1801.