A Significant Collection of Books on American Arts

Collecting and connoisseurship often begin at home, and sometimes result in profound significance and generosity. Long-time friend of Historic Deerfield, Stephen L. Wolf of New York City, grew up in and later operated a family paint business that was founded in 1869.

Instead of turning to other interests in his spare time, Wolf built the premier, private library on the topics of paint, varnish, and color theory dating from the sixteenth century onward resulting in around 1,500 titles. When Wolf passed away in June 2008, he made his long-promised bequest of the library to Historic Deerfield. His generosity, joined by that of his wife Mary and son Matthew, assures in perpetuity the public relevance of his library—and places Historic Deerfield’s reference and rare book collection in this field at the pinnacle of research interest.

Highlights of the collection include: A Tracte Containing the Artes of Curious Paintinge, Carvinge & Buildinge by Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo and Richard Haydocke, A Treatise of Japaning & Varnishing by John Stalker and George Parker, and Grammar of Ornament by Owen Jones. Many of the these books were published during the latter half of the nineteenth century. They join other important titles with a focused interest on New England, such as Conversations on Chemistry by Mrs. Marcet (Jane Haldimand) and J. L. Comstock and A New Collection of Genuine Receipts by Rufus Porter.

The Wolf Collection is available to researchers with an interest in fine art, interior decoration, carriage painting, japanning, color theory, wall treatments, dyeing, enameling, glazing, theatrical set design, art restoration, varnishes, gilding, and the manufacturing of paint. It is housed in the Joseph Peter Spang III Special Collections Room in the Memorial Libraries.

INTRODUCTION

Paint, and the color it provides, is one of the most lasting and influential human developments in art. Centuries after their creation, cave paintings offer us a glimpse into the earliest production of art on earth, as well as the ingenuity that led to the creation of the earliest paints. Peoples all over the world have felt the urge to record their lives, beautify their living spaces, and worship their Gods—and this draw has brought them to the medium of paint.

The constant presence of vibrant color goes largely unnoticed. Pigment is no longer the scarce and highly valuable substance that it once was. Paint has become widely available, something that one experiences constantly. From the shade on their bedroom walls, to the stains and varnishes coating their wooden furniture, to the automobile paint encasing their car and perhaps the nail polish on their hands, paint is an important, if unthought of, part of the modern American’s day. Though they might be taken for granted, the pigments, varnishes, and glazes that surround us have a long and fascinating history.

One of the most knowledgeable men on the subject was Stephen L. Wolf (1917-2008). He dedicated his life to paint, both personally and professionally. Wolf owned and operated S. Wolf’s & Sons, a family business opened in 1869. One of the oldest of its kind in New York City, S. Wolf’s & Sons was a commercial paint and wallcoverings store; supplying the paint for the 1962 repainting of the Empire State Building remains one of its most notable achievements. The store no longer exists today; in 1987 it merged with another independent paint store.

Stephen L. Wolf was incredibly knowledgeable about all things related to paint, as is noted in several articles written about him during his lifetime and after. His expertise was supported by the collection of books and ephemera that he gathered over his lifetime. In 2008 upon his death, Wolf left the contents of his collection on the subject to the Henry N. Flynt Library of Historic Deerfield. His assemblage draws together around 1,500 titles on the subject of paint and varnish, and their respective histories. From pamphlets, to paint chips, to some of the most influential texts ever written on the art of painting, the impressive collection offers an intriguing look into the changes to paint, and more broadly decorating, over the past several centuries. The selections highlighted in this exhibit are only a small portion of the impressive collection that Wolf put together over the course of many years.

History of Color

Paint is intrinsically connected to color, and color theory. Consequently, many of the works in the Stephen L. Wolf Collection focus on color, either as direct instruction into color theory or indirectly as a skill needed for decorating. The range of topics in the collection often emphasize the importance of harmonious color choices, whether in sign painting, scene painting, or decorating.

Color has not always been understood the way that it is today. The Wolf Collection contains many of the premier treatises on color from scientists studying how color works or the chemistry of pigments. Isaac Newton, the famous 17th century scientist, most often known for his work with calculus and gravity, is a crucial figure in our modern understanding of color theory. Until Newton’s experiments in the 1660s, the prevailing ideas about color came from Aristotle in the 4th century BCE. Aristotle posited that all colors were made up of lightness or darkness and the four elements – air, earth, fire, and water. With Newton, color experienced a revolution. Newton’s experiments changed the way that colors were thought of, understood, and perceived.

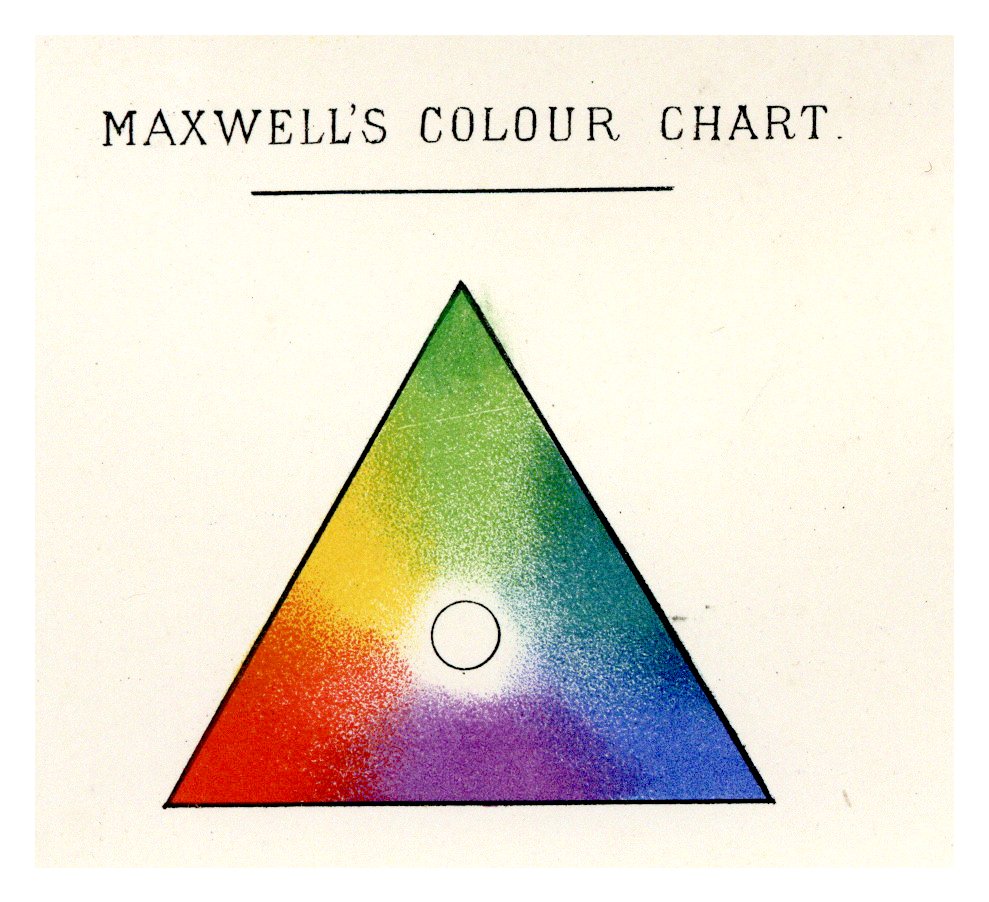

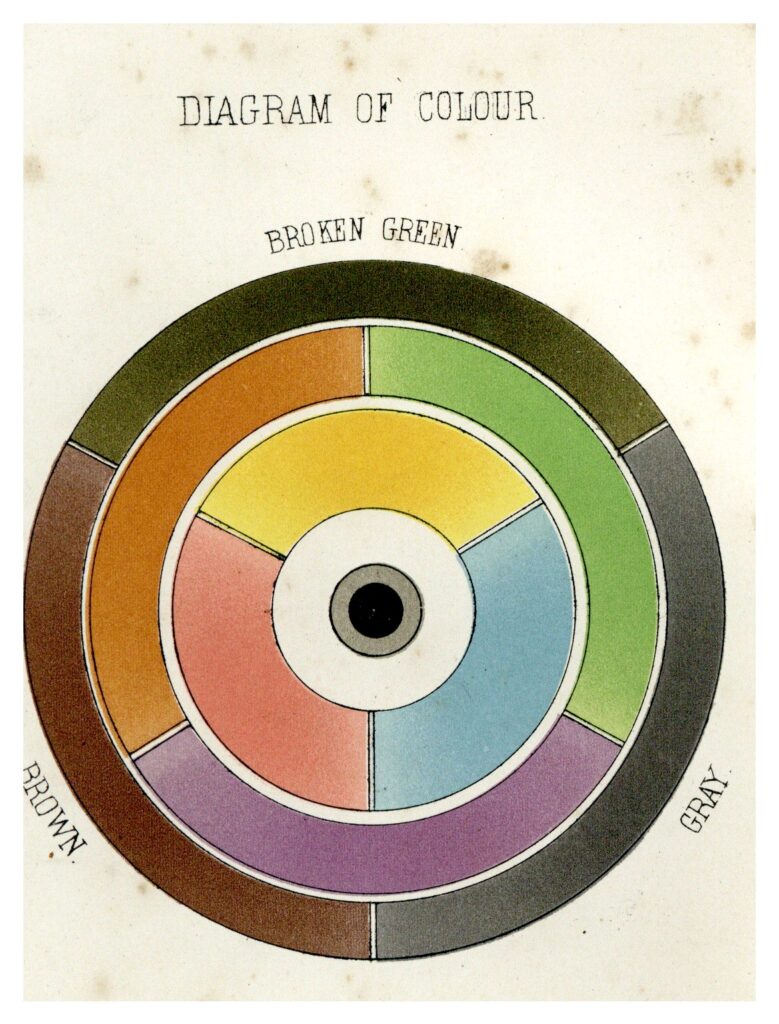

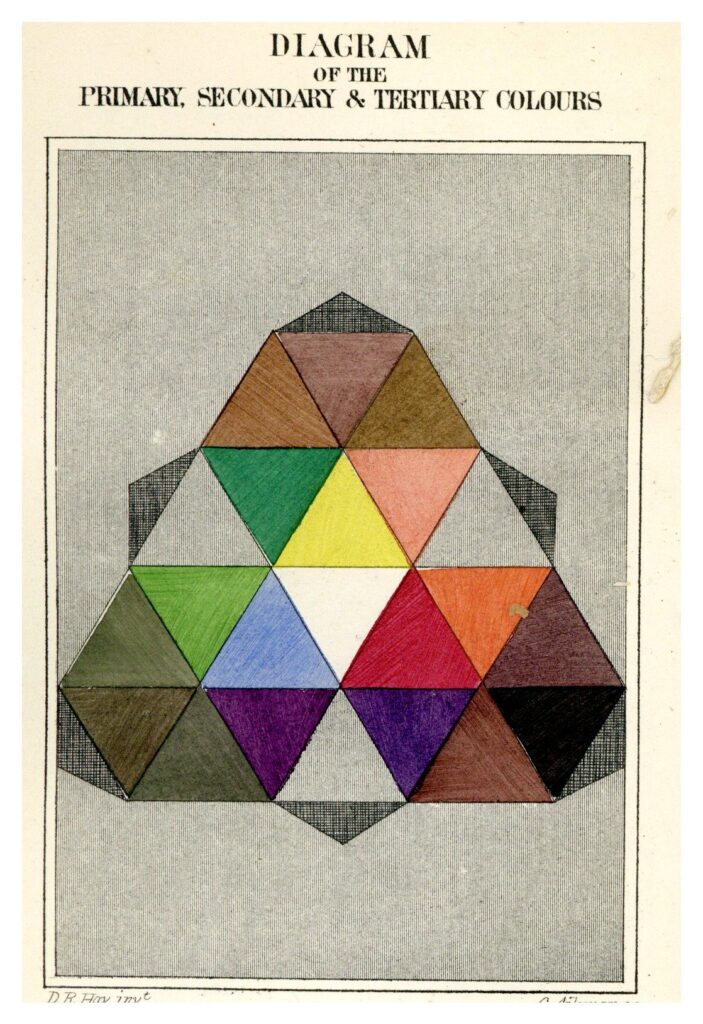

Newton’s famous experiments with glass prisms led to the discovery that white light is a spectrum of colors. [1] He published his new findings and theory about color in 1704 in the work titled Opticks; the Wolf Collection contains a second edition published in 1718. Newton organized his new understanding into the modern color wheel. But at the time that Newton proposed the color wheel, made by wrapping the spectrum of colors he had found onto itself, other members of the scientific community were creating their own representations. In the Wolf Collection there are a number of alternative depictions of how the shades related to one another.

Creation of Paint

The color wheel is the first thing taught in most elementary school art classrooms. The understanding of mixing colors is demonstrated with tiny palettes and enthusiasm. But the effortlessness of this activity has not always been available to all school-aged children, and still isn’t in some places. The modern consumer is most familiar with ready-made, individually packaged paint tubes available at their local craft store or gallons pre-mixed at hardware stores. But in the history of paint, this ease is a relatively new phenomenon.

For most of history artists or painters had to grind pigments in order to mix their own paints. The earliest paints were created from pigments derived from natural materials, and later synthetically derived pigments came into use. Pigments are then bound together into paint with different materials, resulting in varying properties. Tempera paints are made with egg white as the binding agent for the pigment; they provide a matte finish. Oil paints use an oil derived from organic material as the pigment binder. The most common oil used was linseed oil, derived from pressing flax seeds, but other nut oils, such as walnut, also were in use. Oil paints do not dry as fast, and they can be thinned by turpentine. The contemporarily popular acrylic paint, not invented until the 1950s, will not be featured in this exhibition.

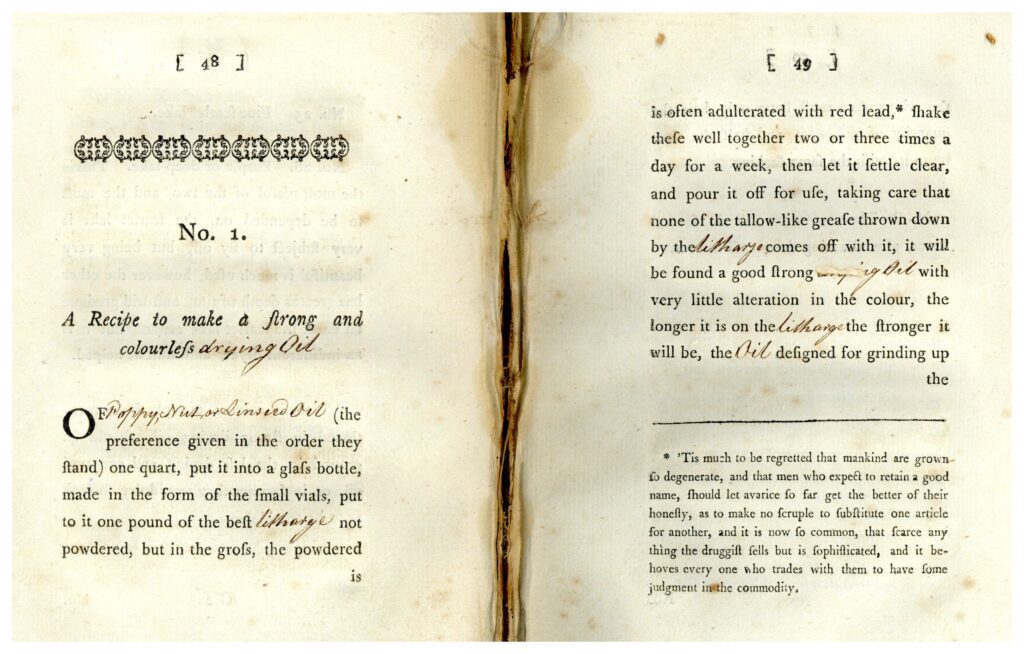

One of the most common similarities among the titles in the Wolf Collection is the inclusion of instructions on the creation of different paints. Whether targeted towards artists, chemists, or tradesmen, many books offer “receipts” (i.e., recipes) for paints, polishes, or varnishes. Since paint had to be handmade from raw ingredients, the author often provides an explanation of important pigments including their qualities and manufacturing, sometimes the writer even will impart tips on how to identify counterfeits. One such book is An Essay on the Mechanics of Oil Colours by William Williams (1787) which allows the reader to customize the recipes to their own specific needs by leaving blank spaces for them to write in their own ingredients.

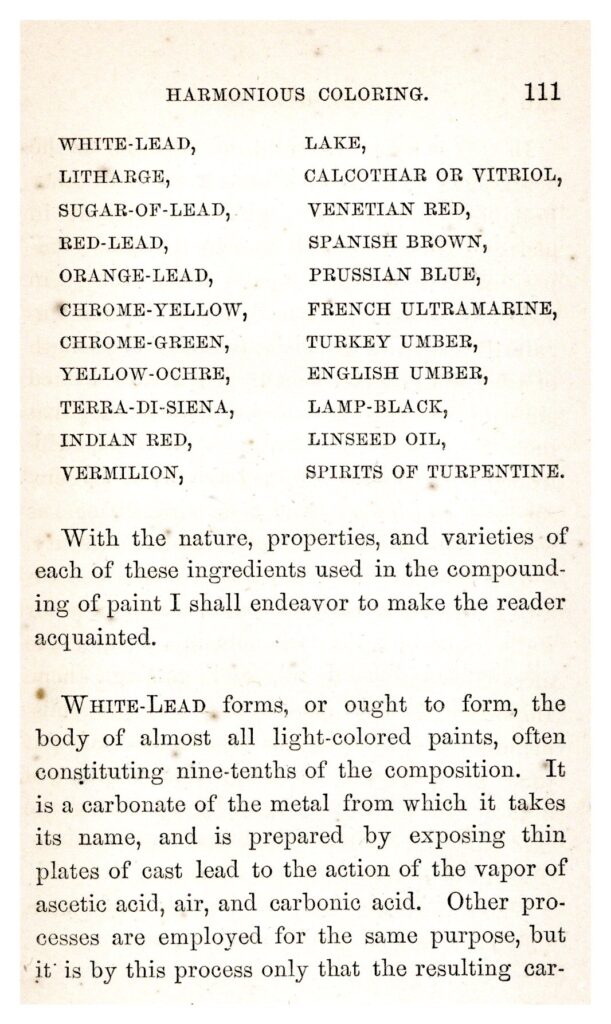

Before the spread of synthetic pigments, forgers tried to take advantage of a market where many pigments were extremely rare and valuable, some being even more expensive than gold. [2] Certain colors, such as blue and purple, were especially precious as they are not often produced in nature. Before the invention of chemical processes to create paint, ultramarine was considered the best blue in the world. Derived from lapis lazuli, originally found in only one mine in Afghanistan, its scarcity made it expensive. Another rare color, Tyrian purple, required several thousand snails to make just one gram. On the other hand, warm earth tones are the easiest to produce from materials found commonly in the natural world. The Laws of Harmonious Coloring by D. R. Hay, published in 1836, is a treatise on the importance of color harmony to all industries, with a specific focus on manufacturing and interior decorating. In it, Hay devotes a long section to explain the properties of the most popular pigment and components of paint. This type of description can be found in most of the early books on painting in the Wolf Collection.

The ways that we make paint have changed drastically over the past few centuries, especially in the ingredients used. One of the largest shifts has been the discontinuing of the use of lead, which almost every book surveyed in the collection made reference to its importance as an ingredient. But since the publication of many of the texts, the adverse health effects of heavy metals have become widespread knowledge. Some of the texts also make reference to the vibrant green produced by highly toxic arsenic.

One of the earlier books in the collection that features paint recipes is The Art of Painting in Oyl by John Smith, published 1705. Smith’s writing focuses on the skill surrounding oil painting, including the “preparing, mixing, and working of Oyl Colours.” The ability to create one’s own paints was a necessary skill for all artists in the early 18th century. [3]

A century later, the importance of mixing one’s own paints had not waned. The 1840 handbook The Painter’s Gilder’s, and Varnisher’s Manual extends the reach of its subject, to include instructions on creating varnishes. Interestingly, along with technical matters, the manual also focuses on the common medical side effects of the profession and gives suggestions on how to treat them. The volume also includes extensive descriptions of the tools and materials used by professionals.

Artistic Ventures

Prior to the 20th century an artist had to know how to produce the proper shades and textures necessary to create their works. Yet today’s appreciators of art do not think about the body of knowledge necessary to make great art. Different paints and their varying qualities contribute to how a finished product looks—artists knew this and adjusted their materials accordingly. These skills didn’t come naturally; instead, they had to be learned through trial and error, an apprenticeship, or book learning. There are many printed works targeting artists that offer an education in the materials, color theory, and techniques necessary for producing a creation. The Wolf Collection contains many of the manuals and treatises on painting that would have been referenced by artists from several different periods.

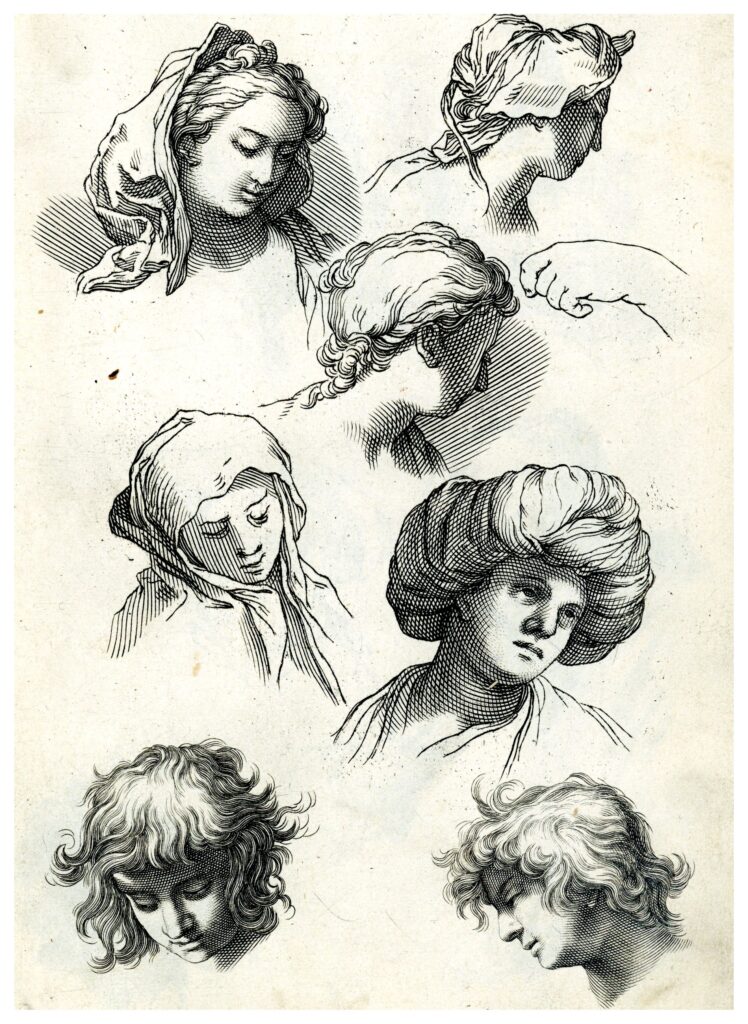

One of the earliest of these books of instructions in the Wolf Collection is Ars Pictoria, written by Alexander Browne and published in 1675. Browne explores the facets of drawing, painting, etching, and description (limning). His instruction is focused mainly on the body, thought to be the pinnacle of an artist’s representation, its proportions, and its movements. This early volume is full of detailed illustrations, concluding with several engravings of sketches for the reader to reference.

A century later in 1756, The Practice of Painting by Thomas Bardwell was published. Differing from Browne, Bardwell focuses on the different layers of a painting, giving detailed instructions for the colors and technique needed for each coat. This volume also focuses on perspective, background painting, and drapery, each a component that contributes to the attractiveness of the final product. Bardwell based his book on intensive study of the work of the old masters; he hoped to replicate their skills and techniques through copying, motivated by the belief that their techniques had been lost to time without being written down.

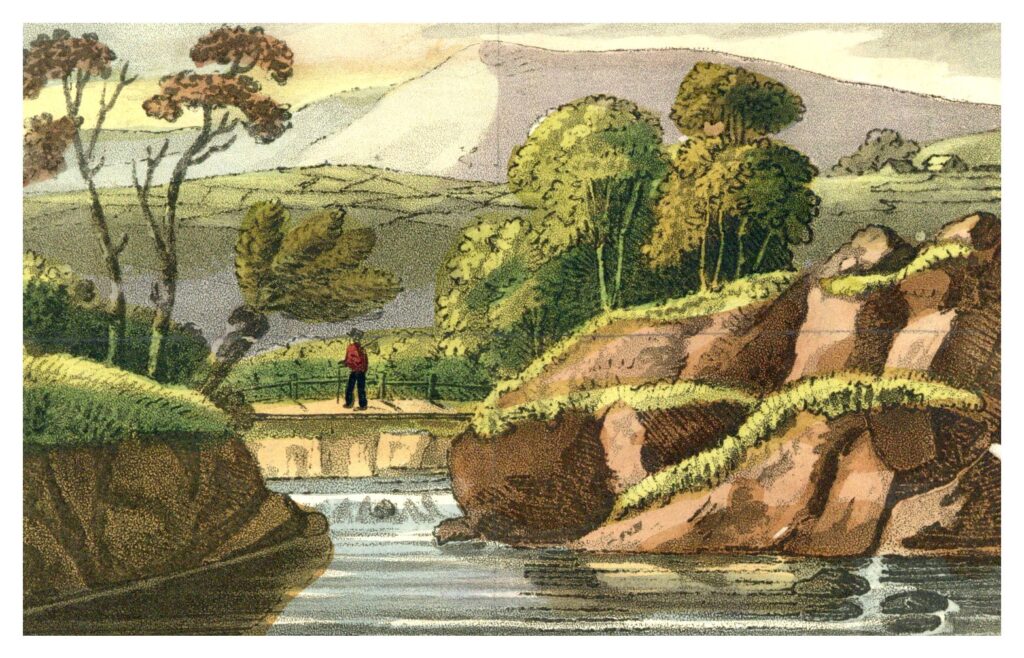

In 1821, John Bulkley authored A Treatise on Landscape Painting in Oil. As time went on, manuals such as these became more specific and focused on a specific type of painting or subject. At the time of Bulkley’s writing there was a movement toward specialization and in this volume Bulkley demonstrates the important things to know about lighting in scene painting. His writing is organized around plates that demonstrate landscape scenes each at a different time of day: morning, noon, evening, twilight, and night.

Similarly, the 1839 On Painting in Oil and Water Colours by T. H. Fielding is a perfect example of this type of focused publication. Fielding provides a guide to painting watercolors and portraits. He includes instructions about which colors to use for each part of the painting. He also includes other necessary details for aspiring artists, such as the materials used in painting and a brief understanding of how paints are produced.

Another specified title from 1844 is The Miniature Painter’s Manual by Nathaniel Whittock. This little volume focuses on the art of miniature painting, giving the reader advice on how to paint on materials, from cardboard to ivory, as well as more typical ones such as canvas and paper. Whittock also takes a holistic approach and addresses all aspects of the painting, from the figure to the background. This book was published on the eve of the popularity of photography, which had been introduced a few years earlier in 1839, [4] an art that would come to replace the practice of miniature painting.

What is a Lithograph?

Many books in the Wolf Collection, and several selected for this exhibit, feature prominent colored lithographs. This technique was the premier way of printing color images for several decades before the advent of more advanced processes. Prior to the lithograph technique, color in printed books had to be hand-drawn onto black and white engravings, a process that took time and didn’t produce uniform copies. The lithograph technique was invented in 1798 by Aloys Senefelder. The process involves using a different printing surface (most often a slab of limestone) for each color. The artist draws directly on the stone with a greasy substance, like a wax pencil, and afterwards the surface is treated so that ink will only attach to the desired spaces. [5] The process creates a unique way of printing, because it captures each stroke of the artist’s pencil. A lithograph is a beautiful product that looks like it’s been drawn by hand. But the precise nature of having to run each sheet through the press several times meant that there was great time and expense that went into each plate. The unique colored results produced through the lithographic process meant that it was common for publishers to advertise how many each volume had.

Interior Decorating

The interior of houses and buildings can be a place to demonstrate one’s personal taste and style. It is also a place that requires maintenance. The work of interior decorators varied, and the Wolf Collection addresses many facets in several manuals. The decorator used any array of tools to form the desired interior effect for their home or client.

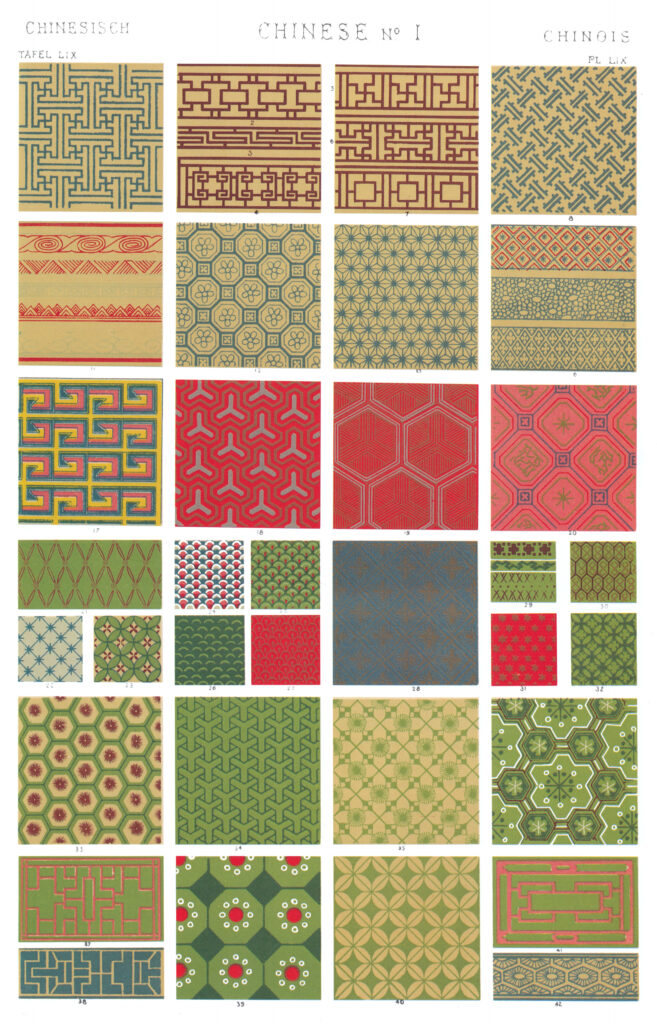

The Grammar of Ornament by Owen Jones (1856) became an extremely famous and influential text. The book is best known for its 112 full-color plates depicting famous styles and designs from around the world. Chapters include plates highlighting different design/ornament styles from cultures around the world. Each lithograph draws in the viewer and captures their attention with the detailed intricacy and vibrant color. Flipping through The Grammar of Ornament feels almost like stepping into the regions that it depicts, with Jones bringing to life on paper the designs of Egypt, India, Greece, as well as many others.

A standout in this category is the 1878 The Paper Hanger, Painter, Grainer and Decorator’s Assistant attributed only to “A Decorator.” Decorating is a theme that shows up in several books, and though painting is an important part of their job, this publication also includes information on how to hang pictures satisfactorily and examples of lettering styles. This volume specifically devotes much space to wallpaper (referred to as paper hangings) and stenciling. Developments in production allowed for an explosion of wallpapers onto the market. As new ways to decorate one’s home developed, new publications sprang up to provide expertise.

The American Grainers’ Hand-Book from 1872, published by John W. Masury & Son, a Brooklyn based paint company, is an instruction manual for creating realistic wood grains out of paint. It includes 14 different full-page colorful examples of popular woodgrains that the manual instructs the reader to create. Masury & Son give detailed explanations and engravings of the types of brushes and tools used to create the faux grains.

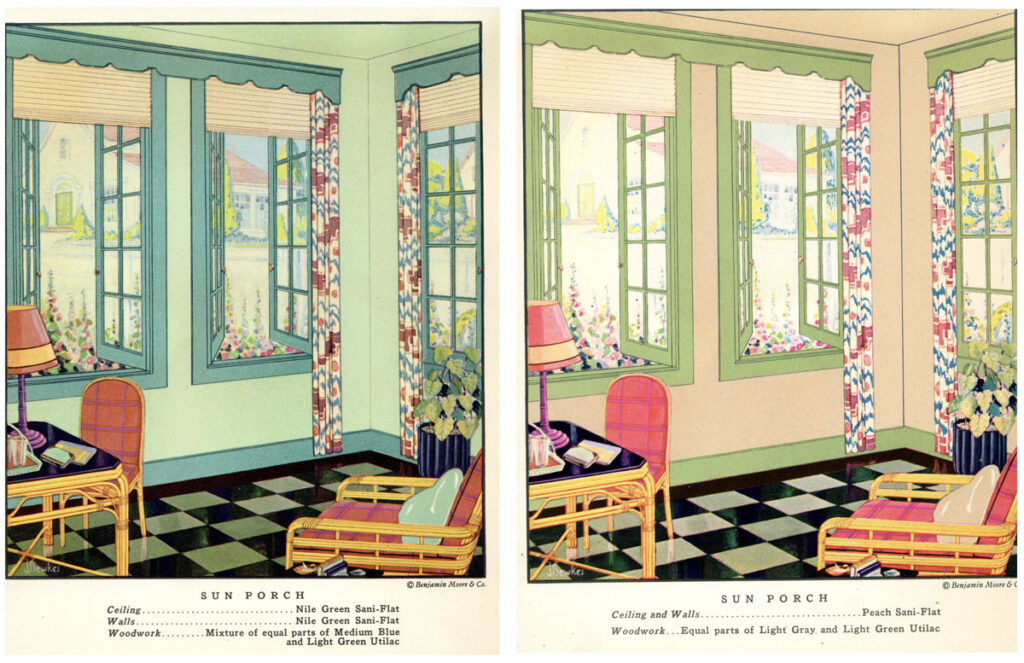

Some of the volumes after 1900 in the Stephen L. Wolf Collection focus on the new ability for American consumers of all classes to customize their houses. The brilliantly colored paint catalogs from the early 20th century showcase a unique look into the idealized American home. The catalogs function as ads for the suitability of their own paints and supplies in the creation of a trendy and modern house.

Andrew Millar’s 1909 text, Scumbling and Colour Glazing, focuses on some of the techniques known to create a more high-end look. These techniques were not used exclusively on interior painting, as they could also be applied to fine art or coach painting. Millar’s instructional text addressed wishing to learn the practices of scumbling or glazing. He goes through techniques, materials, and best practices. Millar’s book is filled to the brim with paint swatches showing examples of glazing and scumbling; they are especially interesting to observe the change to the swatches over a century from fading and discoloration.

Many of these home decorating catalogs specifically focus on the harmony of colors, a holdover from the late 19th century. The catalogs often show the same room decorated different ways. In the still popular brand Benjamin Moore & Co.’s 1930 viewbook, Practical Suggestions for Interior and Exterior Decoration, colored plates are set side by side, each advertising a different way of styling rooms in the home, from the kitchen to the bedroom. This ingenious style of advertising conjured up images of the most idyllic home, then skillfully provided everything you needed to make it yours.

Exterior Decorating

Just as in interior decorating, exterior paint has many important functions, but is most noted for its aesthetic appeal. The exterior color of a building can be a strong indication of wealth, status, or function. Paint and other wood treatments can help to prevent weathering of buildings, and increase the longevity of the structure.

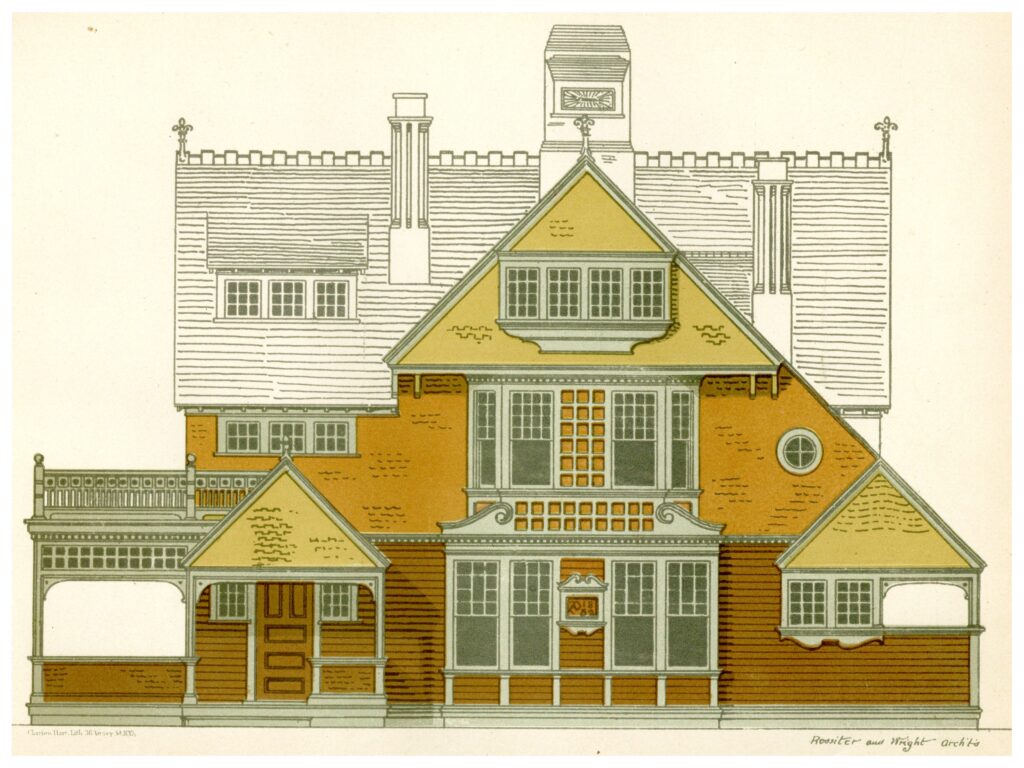

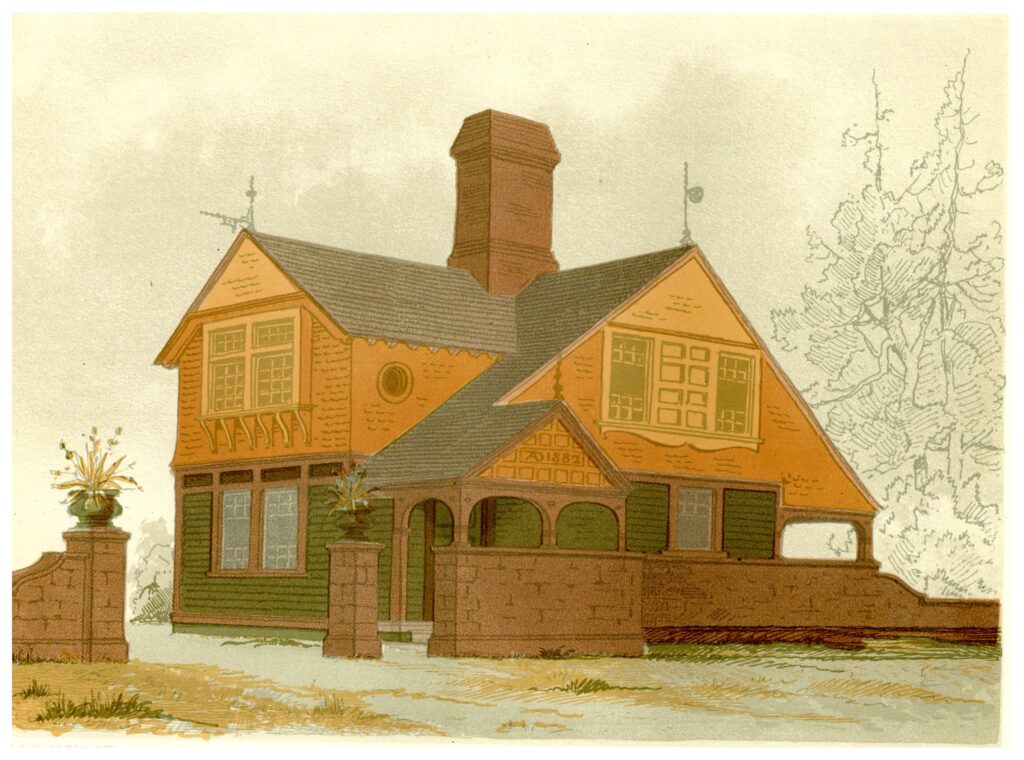

One of the most beautiful books in the Wolf Collection is E. K. Rossiter and F. A. Wright’s Modern House Painting compiled in 1882. This volume discusses the best colors and techniques for house painting, and is famous for its 20 beautifully colored lithographs. Each full-page illustration shows different styles of houses painted in various ways. Along with each is a description of why the colors suit the style of the house in question. Though Rossiter and Wright focus mainly on the exterior of contemporary houses, there are a few plates dedicated to interior color design and the importance of color harmony is yet again highlighted. Modern House Painting manages to capture the ideals of a stately well-maintained American house in the late 19th century.

Exterior painting requires a variety of paints and brushes. The Catalogue and Priced List of Materials… of C.T. Raynolds & Co. is an fascinating look into the 1892 world of exterior painting. The catalog covers all the things that an artist or professional painter could want. Though it starts with a focus on paint tubes, there is a large section devoted to brushes used by workmen including many images of the different brush types. The large brushes can be used for paint or varnish, on a variety of surfaces from wooden exterior faces to roofs.

Transportation

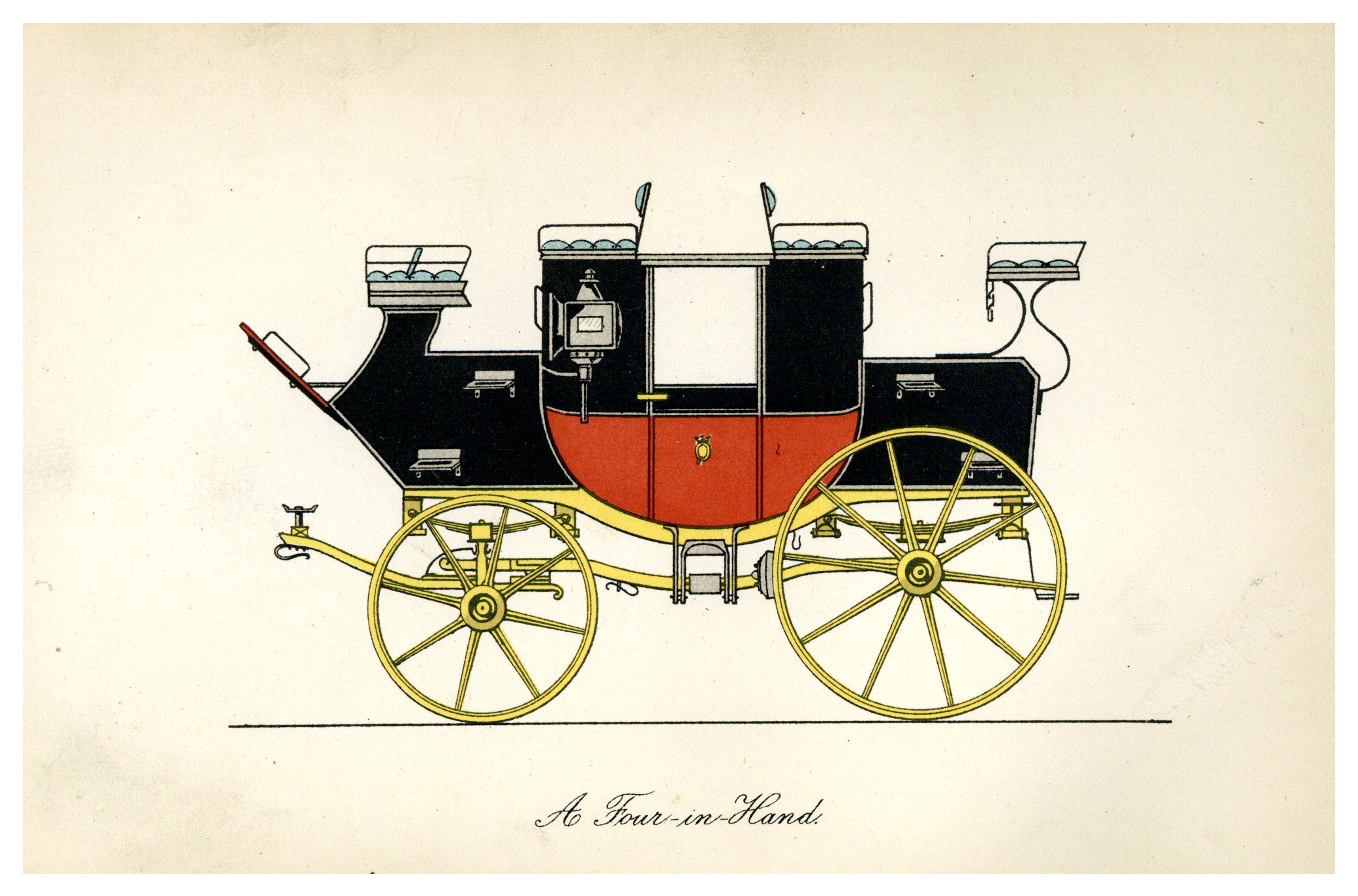

Paint has become a staple of modern travel. The roots of today’s flashy car colors are found in past train and carriage painting. Transportation vehicles have long since been a symbol of elite status; though a Lamborghini might not have the intricate painting of an 18th-century coach, its value is well known to onlookers.

The painting of transportation vehicles stems from the important role that paint plays in the longevity of the vehicle. From modern cars to historic carriages, the treatments that are added to the body hold both aesthetic but also intensely practical applications. Varnishes and other treatments protect the wood or metal from the elements. The techniques applied to vehicles have the effect of making them durable and protected from the many situations that they will face in their travels. Paint used on vehicles needs to withstand beating sun, pouring rain, high speeds, and freezing temperatures.

Before the full metal bodies of automobiles and train cars, carriages were the main form of wheeled transportation, and painting them was an extensive art. There are several books in the Wolf Collection devoted to the trade, but one of the finest among them is The Complete Carriage and Wagon Painter by Fritz Schriber, circa 1895. In this guide Schriber covers painting not only carriages and wagons, but also sleighs, offering a glimpse into the now obsolete art. It includes examples of different design features and instructions on several lettering styles.

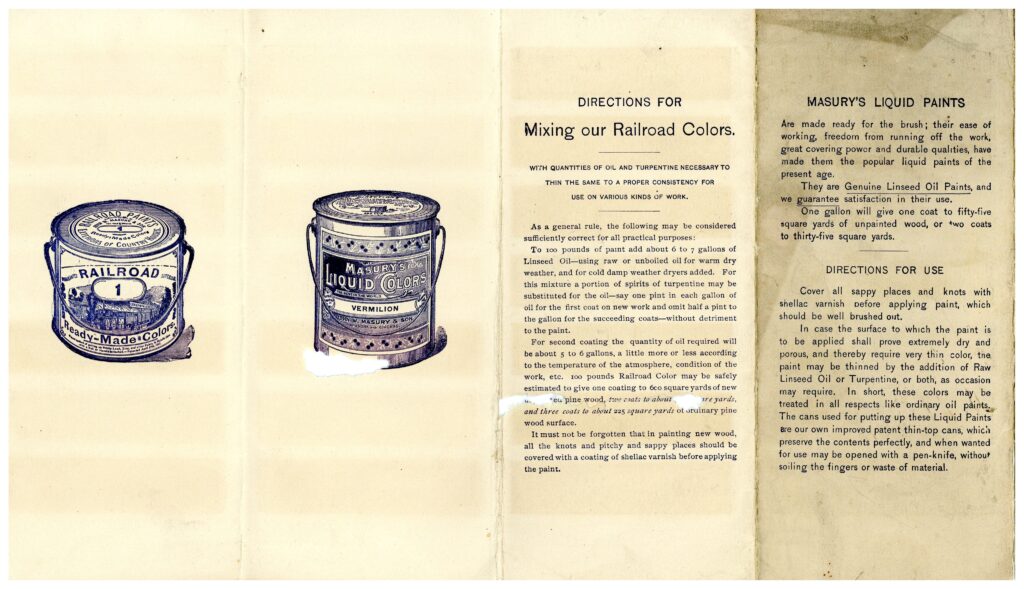

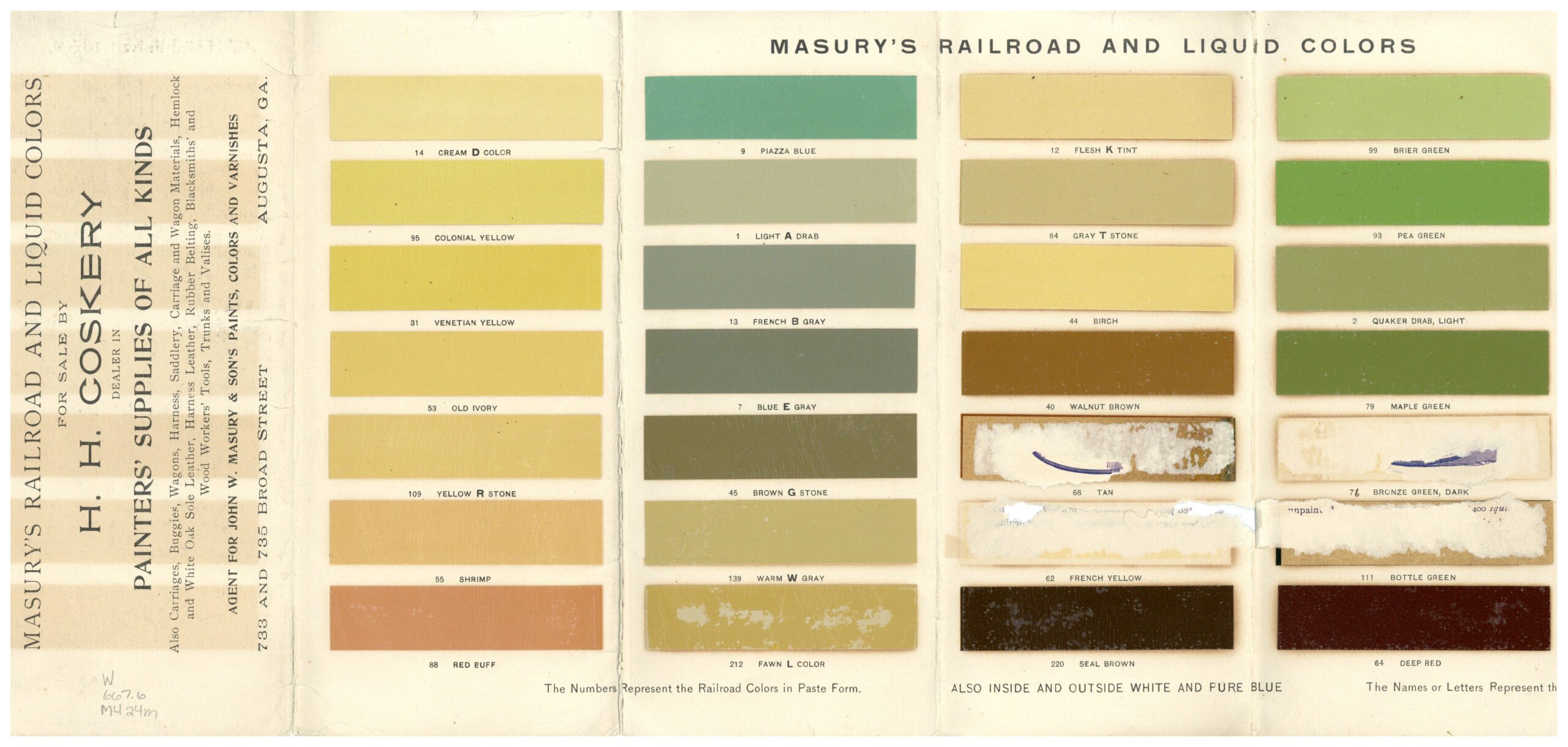

Paint companies expanded their customer base with the introduction of trains into the American consciousness. Trains, like all other mechanisms for conveying people and things, required specially produced paints. Masury’s Ready Made Colors, distributed by the company of John W. Masury & Son, is a pamphlet dedicated to promoting their paints advertised for just that purpose. In this 19th-century booklet, 35 different color swatches of Masury’s Railroad and Liquid Colors are on display. Additional advertisement text promotes the superiority of Masury paint at its unrivaled cost. Though it is described as liquid paint, meaning that it comes in cans, the pamphlet still includes a section explaining how to prepare and mix the paint for proper use.

John W. Masury & Son [6]

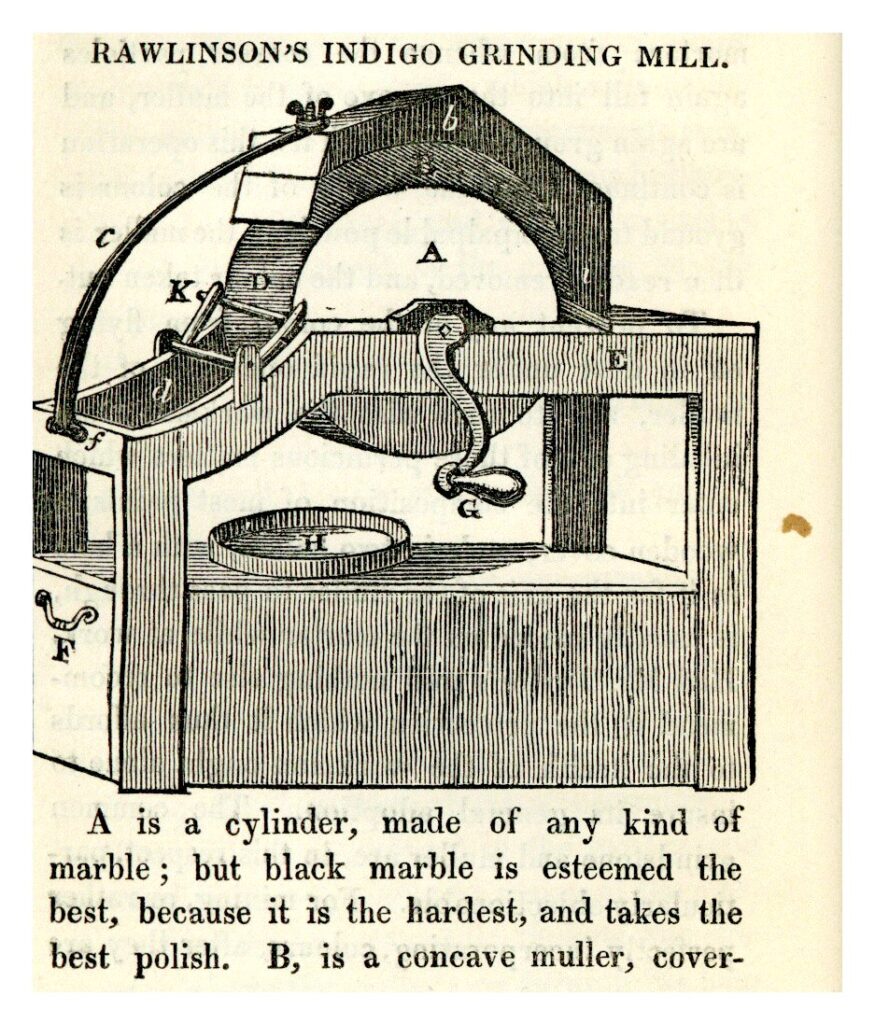

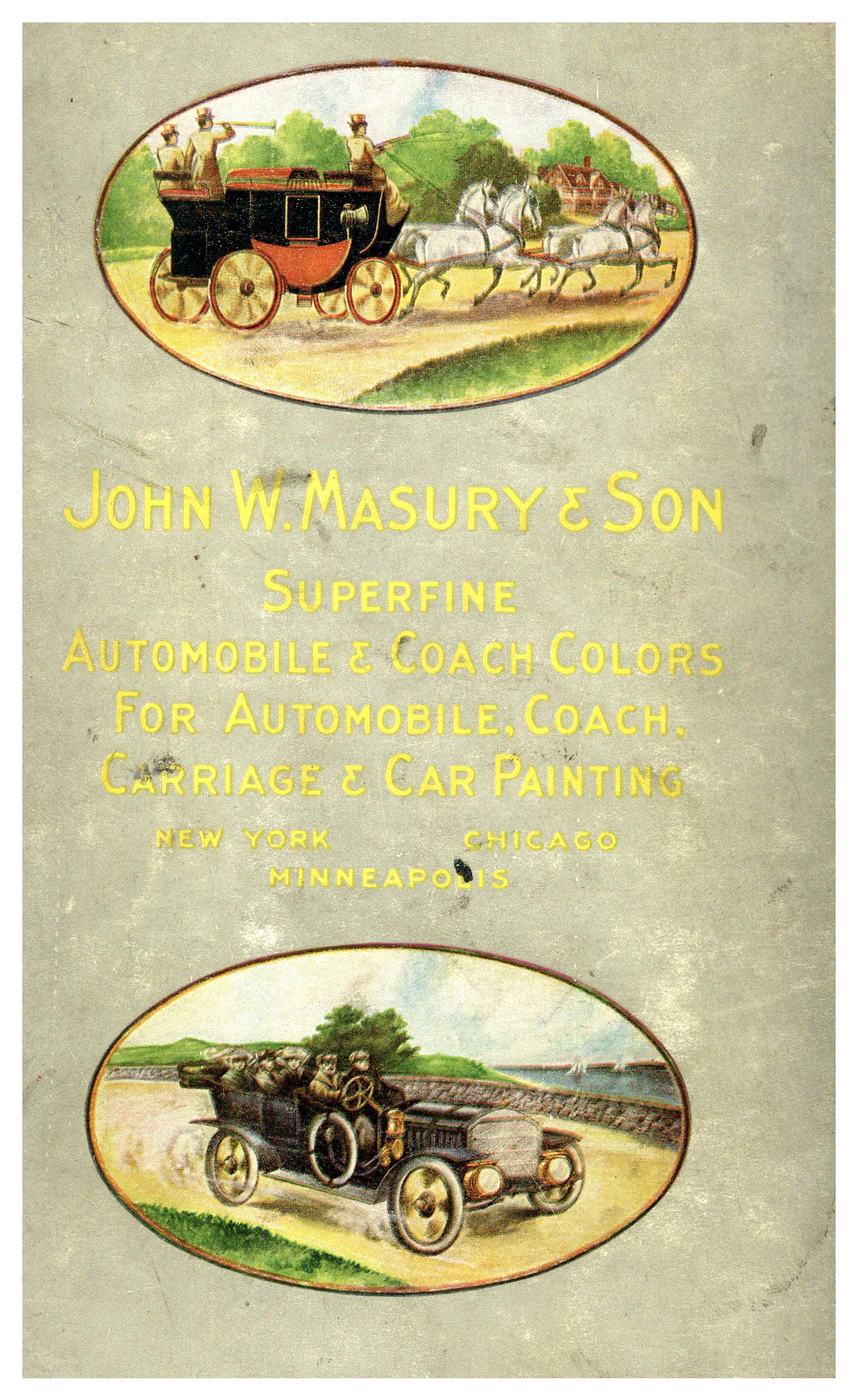

The Wolf Collection contains several items distributed by the Masury & Son company, originally located in Brooklyn, NY. Today the Henry N. Flynt Library holds a number of paint catalogs, manuals, and advertising materials from the several decades that the business was in operation. John W. Masury built a paint empire. At his start in the mid-19th century when the creation of paint was still a laborious process, Masury pushed for the factory production of paint, a move that worked well and earned him immense wealth. Originally the company started as a collaboration, but by 1870 he was the sole owner, changing the name to “John W. Masury” and five years later he renamed it “John W. Masury & Son.” In addition to his revolutionary industrialization of the paint-making process with a mechanism for grinding paints, he is best known for the creation of the resealable metal paint can lid. Eventually manufacturing moved to Baltimore in the 1940s, and later the company was sold to the Valspar Paint Corporation in 1979 when the Masury line was discontinued.

The increase in mechanization at the start of the 20th century did not dissuade the popularity of horse-drawn vehicles. In 1906, M. C. Hillick wrote Practical Carriage and Wagon Painting, which covers everything from the necessary equipment in the shop of a painter, to the best colors to use and how to mix them. There are also instructions to create the most popular decorations, with depictions of what they are supposed to look like and the brushes needed to achieve them. But interestingly, Hillick acknowledges the changing world around him by providing in the final chapter a short guide to automobile painting.

In the early 20th century coaches and cars shared the road, though the latter would quickly come to dominate the pavement; contemporary paint companies catered to both forms of transportation. From this period comes John W. Masury & Son’s advertising booklet, Superfine Automobile & Coach Colors, bound in a colorful cardboard cover with depictions of subjects driving both cars and carriages. Inside the delightful covers is a selection of Masury paint samples, with each page protected by a sheet of tissue paper. There are instructions for use and lists of color names at the beginning of the book. This is an unusual piece of history to survive as it is not a traditional book, but rather a selection of paint swatches that wouldn’t usually find its way into a typical library. In this way the Stephen L. Wolf Collection is unique in its contents.

Advertising

Most of the books and ephemera in the Wolf Collection act not only as educational texts, but also as advertisements. Many volumes include lists of other books by the publisher that are available for purchase. Several texts written by companies as sale booklets often add advertising specific to their own products. Notably there are many books that simply include full-page ads for products related to their subject, most often paints and brushes, in the back of the book. Ads like these are a useful look into what the then-contemporary consumer was viewing, as well as the popular products and their costs.

A portion of books in the Wolf Collection are dedicated to sign painting, a skill most commonly associated with advertising pursuits. The job requires the ability to produce beautiful uniform lettering in several styles. In the collection are several examples of alphabets that a tradesman could learn, as well as beginner instruction manuals on the art, explaining how to draw each letterform precisely and consistently. In 1940, E. C. Matthews revised his earlier version of the work How to Paint Signs and Show Cards. In this printing he draws together new improvements, such as advances in glass painting and silk screening. This introductory text is filled with directions on the best way to go about learning to be a sign painter. In addition to advice it is full of examples of the entire process, from alphabets to layouts to final products.

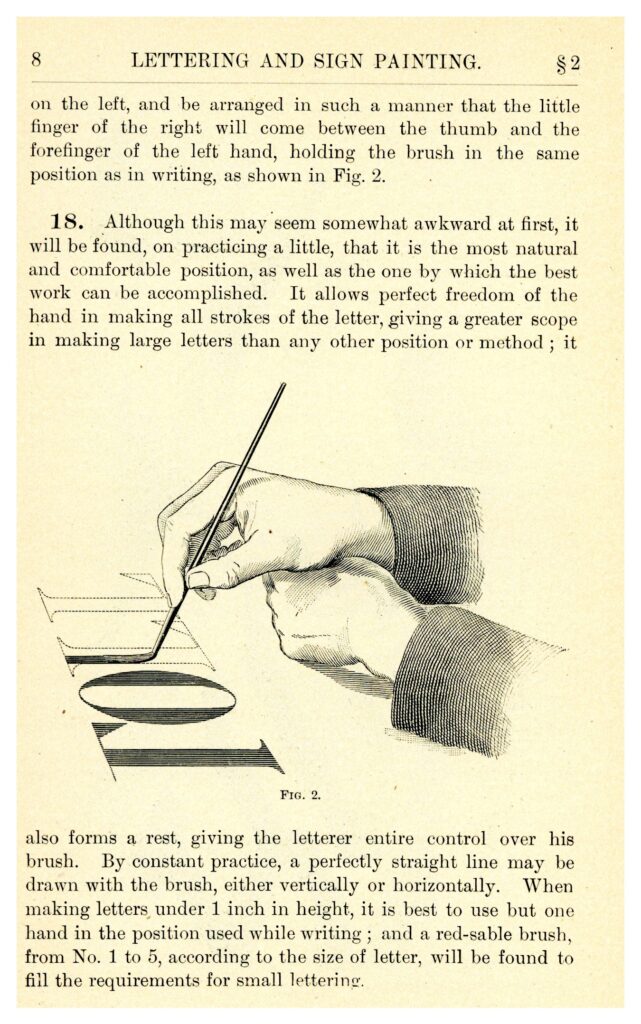

A noteworthy educational text from the turn of the century is Elements of Lettering and Sign Painting published by International Correspondence Schools as a part of a correspondence-based course. The first half of the book focuses on lettering; the second part of the volume aims to use the skills acquired in the first section and to apply them specifically to sign painting. Each part of the study is broken down into smaller sections and defined; for example, when describing sign painting, the course includes illustrations that depict where the hand should be positioned in order to produce the desired effect. One element that the course gives special attention to is the practice of stenciling, shown with detailed step-by-step illustrations.

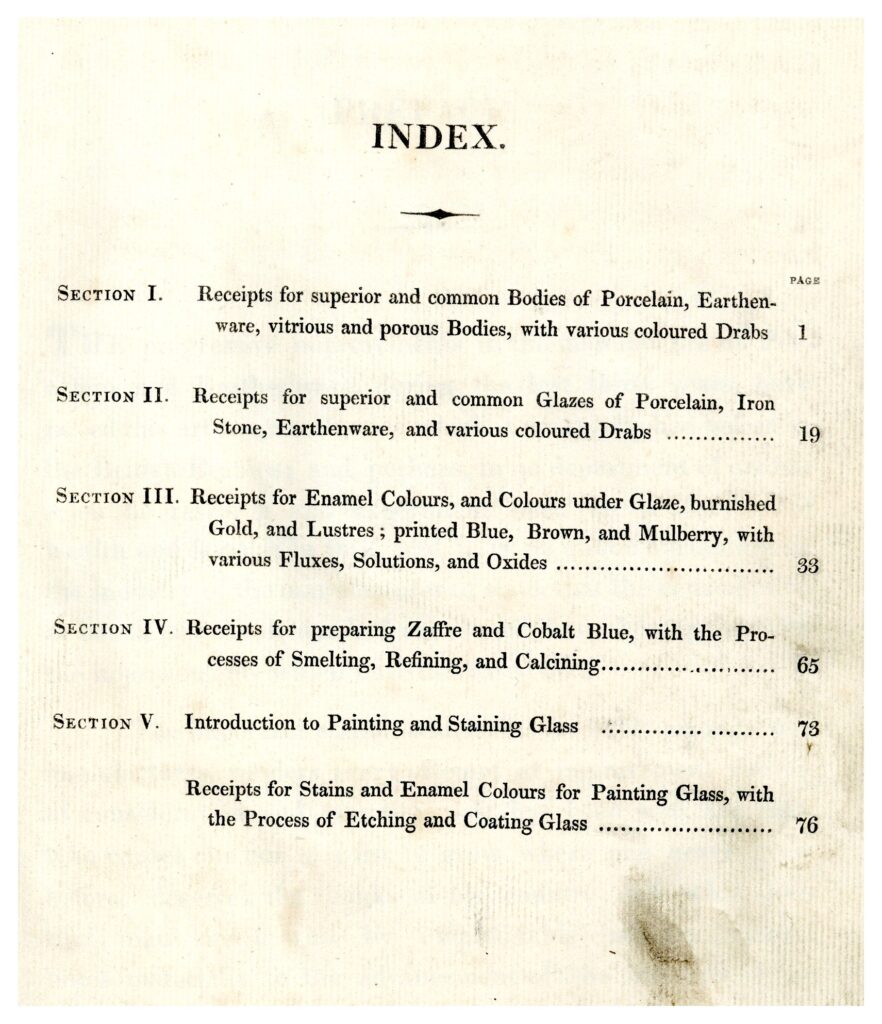

In addition to signs, painted glass formed another popular effect in advertising. The tricky and precise art became popular alongside the rise in production of affordable glass; the technique was otherwise known as enameling. The 1824 Potting, Enameling, and Glass Staining, written by an unnamed author, focuses on unusual painted surfaces like ceramic and glass. Like other books in the Wolf Collection it is full of instructions for the creation of different colors, stains, and glazes, but many recipes require the item to be fired at some point. The Wolf Collection’s copy is full of the evidence of its former owners; it seems that at one point one was used as a practice surface for penmanship. Though the blue marbled cover has faded it provides a glimpse into the stylistic and economic choices of the person who had it bound.

Written by Claire Sullivan, Smith College – 2023 Memorial Libraries Summer Intern

[1] In order to learn more about Newton’s experiments and processes with color, visit the Cambridge University Library’s YouTube channel for a lecture on the his education and investigations, entitled The Origins of Colour.

[2] Though pigment collections were once a common part of all artists’ studios, premixed paints have become the standard. The Harvard Art Museum in Cambridge holds one of the premier collections of pigments (more than 2,700 different varieties).

[3] The University of Delaware produced a wonderful video that shows how artists would have produced the oil paints that they used.

[4] At its start, what we know as photography today was known as “daguerreotype,” named for its inventor Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. The process was the result of years of work, but he eventually achieved success in capturing the temporary images shown by a camera obscura.

[5] For those interested, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s article detailing the process of lithography includes explanations of the materials used and wonderful short clips of each part of the process.

[6] This summary was compiled with reference to The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, The NYTimes Archive, and Patrick Mcheffey.