Branches of Woodworking

Labor, Learning & Livelihood

1760-1860

Introduction

What do wooden objects reveal about their makers and the tools used to create them? Woodworkers employed a variety of skills and tools to satisfy customers’ demands for everything from high-style furniture to agricultural implements. The objects in this exhibition, including an exterior gutter fragment, an ox yoke, a footwarmer, and a mantel testify to the diverse scope of work practiced by different kinds of woodworkers. As a growing population and an expanding economy increased demand, woodworkers brought to bear the knowledge and experience gained through their deft use of hand tools to achieve good design and functionality. Proper training and an entrepreneurial spirit defined successful craftsmen as they tackled all branches of the craft, from timber framing houses to joinery, cabinetmaking, turning, wheelwrighting, coopering, carpentry, and repair work.

Samuel Gaylord Jr. Entryway Vitrine

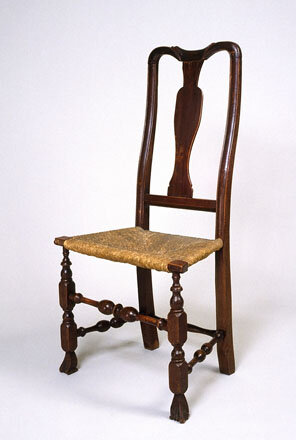

In 18th-century agrarian society, artisan trade work like woodworking supplemented the livelihoods of those who were farmers. Samuel Gaylord, Jr. (1742-1816) of Hadley, Massachusetts, exemplifies woodworkers in rural western Massachusetts during the 1700s. The objects here, including a bannister chair attributed to him, are examples of the types of products made in the Gaylord shop. Excerpts from his account book dating from 1763 to 1793 provide evidence that Gaylord, his apprentices, journeymen, and hired hands performed farm labor as well as making and repairing farm implements like the block and tackle and shovel shown here.

Who Was Samuel Gaylord, Jr.?

Born in Hadley, Massachusetts, Samuel Gaylord, Jr. (1742-1816) apprenticed with his half-brother Samuel Partridge (1730-1809), Obadiah Dickinson (1704-1788), and Moses Graves (1700-1785). In 1763, at the age of 21, he began an artisanal career that encompassed diversified work with multiple streams of income – from woodwork to selling building supplies, farmwork to generating income from assets such as livestock. With his second marriage to Penelope Williams (1745-1815) in 1770, Gaylord developed kinship ties to Hadley’s wealthiest families, which in turn helped him to expand his business as a skilled craftsman. Gaylord’s shop produced over 1,982 finished objects during the 30-year span of his account book.

*This symbol indicates entries from Samuel Gaylord Jr.’s, account book, 1763-1793, Historic Deerfield Library.

Objects:

To view an object, click on the photo. To see the object label information, hover over the picture with your mouse on a desktop computer or click the small diamond at the bottom right of the photo when viewing on a mobile device.

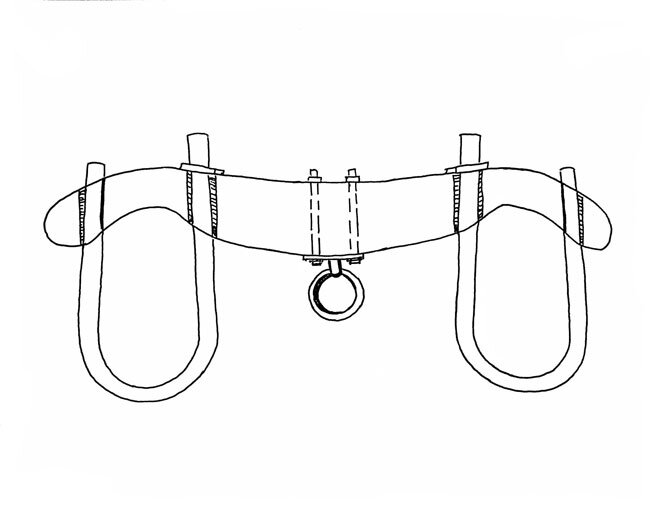

Designed for Strength & Comfort

A yoke is tailored to fit specific animals and tasks. A comfortable ox will work hard.

A: Bows are custom fit to each oxen’s neck. B: The distance between the bows depends on the task. Longer keeps the oxen further apart, enabling more maneuverability for cart pulling. Shorter keeps the animals closer together to concentrate force for heavy work like plowing and log hauling. C: The underside is rounded to remove sharp corners.

Objects:

To view an object, click on the photo. To see the object label information, hover over the picture with your mouse on a desktop computer or click the small diamond at the bottom right of the photo when viewing on a mobile device.

Center Vitrine

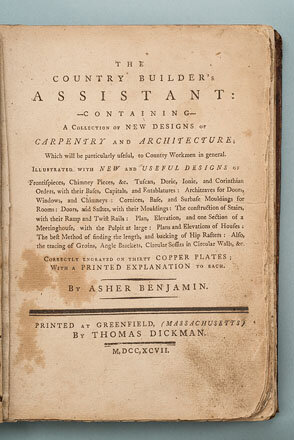

Ambitious craftsmen in company with other tradesmen sought to expand business in the decades following the American Revolution. New fashions and consumer optimism drove customer demand for functional and stylish architecture, tools, and household items. Published collections of formal designs guided architects and artisans. These pattern books spread popular taste throughout the eastern United States. Objects here illustrate how rural woodworkers created new items in response to fashions established in urban seaports.

A Child’s Cradle or an Agricultural Cradle?

Likely both. Gaylord made many different types of furniture and a wide variety of farm and household implements. His account book has many entries for cradles.

*August 29, 1770: “to a cradle £ 0:5:4” as well as two bedsteads and a tester (the horizontal framework mounted on four bedposts to support a canopy). This entry likely refers to a child’s cradle.

*While the entry for May 8, 1770: “for altering youre cradle £ 0:2:0” suggests that he made repairs to an agricultural implement. The long thin fingers on a cradle scythe, made to catch long stemmed grains during harvest, were prone to breakage.

Objects:

To view an object, click on the photo. To see the object label information, hover over the picture with your mouse on a desktop computer or click the small diamond at the bottom right of the photo when viewing on a mobile device.

Asher Benjamin

Objects:

To view an object, click on the photo. To see the object label information, hover over the picture with your mouse on a desktop computer or click the small diamond at the bottom right of the photo when viewing on a mobile device.

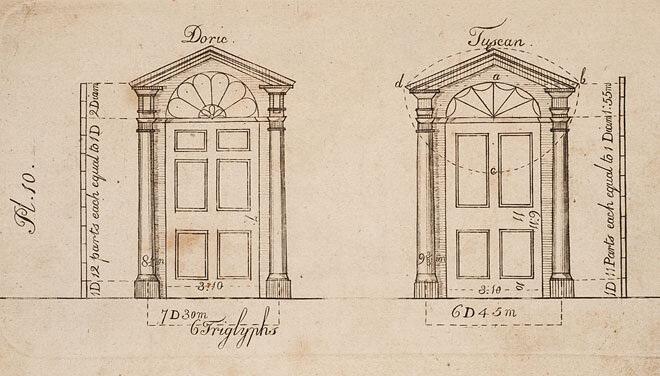

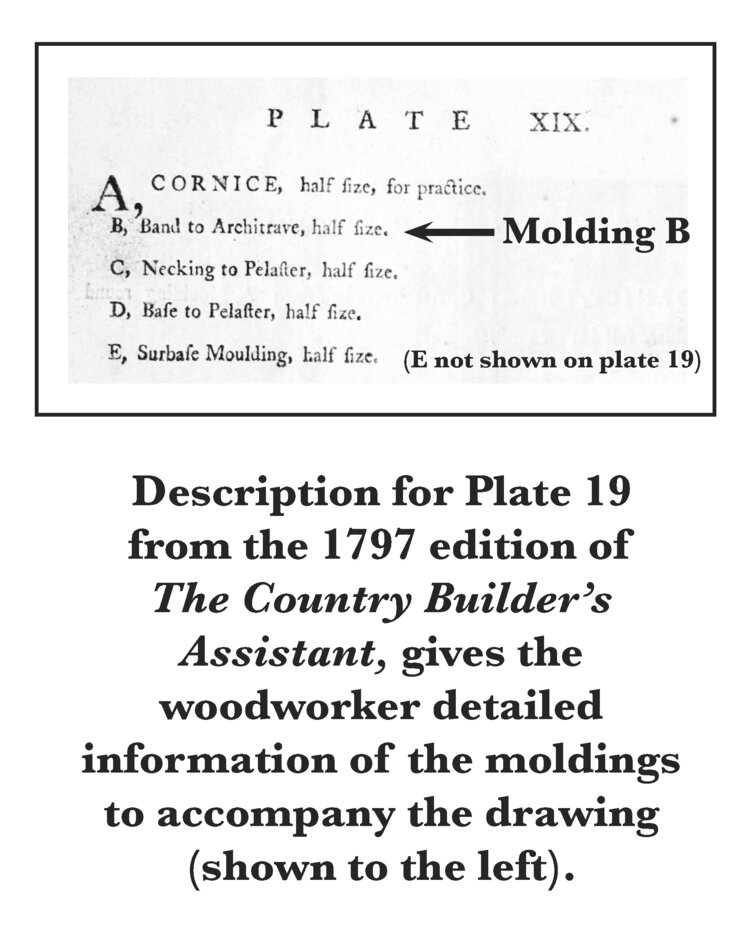

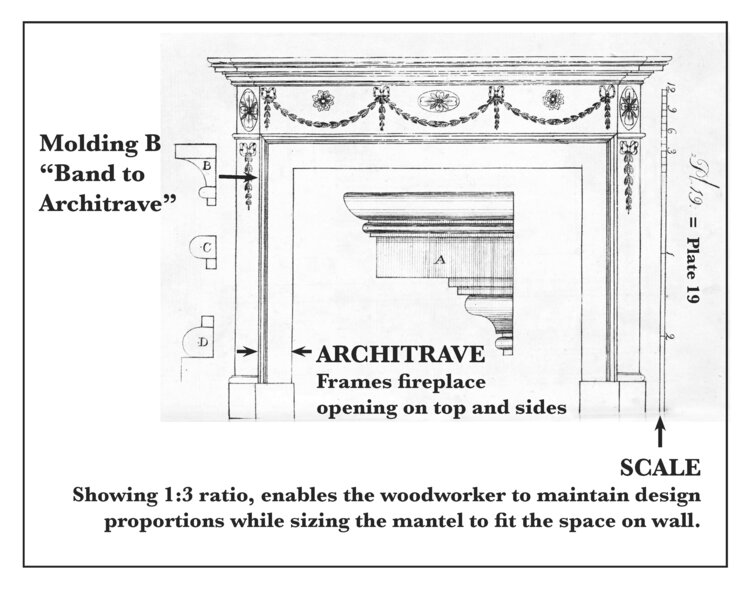

Pattern Books Were Guidelines, Not Blueprints

The mantel pattern shown here is plate 19 of the first edition of Asher Benjamin’s The Country Builder’s Assistant. Aspects of the design, the swags of bellflowers, flower medallions, and ribbons are depicted in the mantel on the wall to your right. But not all of the elements were produced according to Benjamin’s design; pattern books were guidelines, not blueprints. Look at the architrave (molded frame around the fireplace opening). Molding detail B as seen in the pattern book has: a fillet over a cove, followed by a bead then a quirk (flat), but it was produced on the mantel (shown in the illustration to its right) with: an astragal (bead) over a smaller cove and finished with a partial bead. The combination of elements in each example achieves the same flowing transition from the higher outer surfaces to the lower inner frame, while subtly expressing different aesthetics.

Mounted on Wall

To view an object, click on the photo. To see the object label information, hover over the picture with your mouse on a desktop computer or click the small diamond at the bottom right of the photo when viewing on a mobile device.

Rice Wall Vitrine

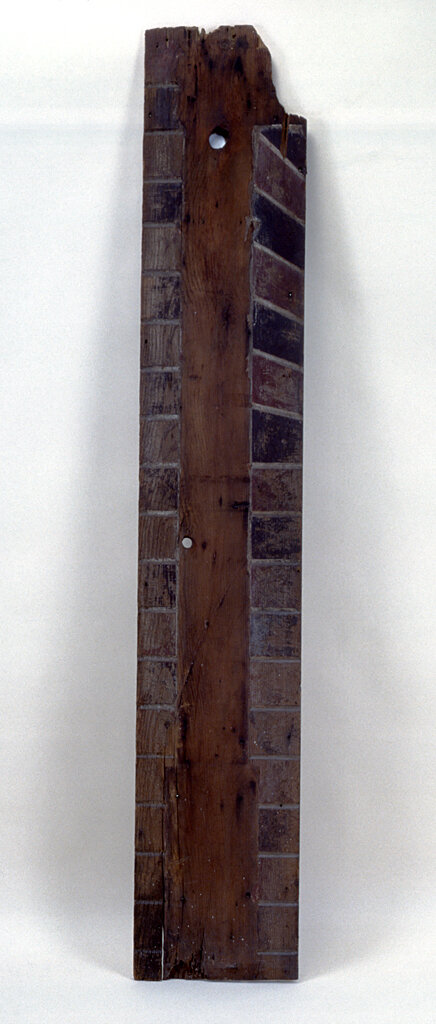

As the nation’s population grew during the 19th century, so did the demand for wooden products and the hand tools woodworkers needed to create them. Planemaking became a woodworking specialization as the trade diversified over the course of the century. The beech forests of western Massachusetts provided the main resource for planemakers like Daniel Rice (1818-1899), who with other makers of molding planes responded to changing architectural styles by creating new profiles based on neoclassical, Grecian-inspired elliptical shapes.

Who Was Daniel Rice?

Daniel Rice was born in 1818 in Hawley, Massachusetts. In 1836, at the age of 18, Rice moved to Conway, Massachusetts, where he learned carpentry and worked in the trade for 14 years. On April 15, 1850, Rice co-founded the planemaking firm, Conway Tool Company. Within a year, a fire destroyed their building, the company was re-formed as the Greenfield Tool Company in Greenfield, Massachusetts. After making planes for 12 years, Rice moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, where he worked as a master builder until 1889. These planes were part of a set used by Daniel Rice, whose tool chest and contents are owned by the museum.

Objects:

To view an object, click on the photo. To see the object label information, hover over the picture with your mouse on a desktop computer or click the small diamond at the bottom right of the photo when viewing on a mobile device.

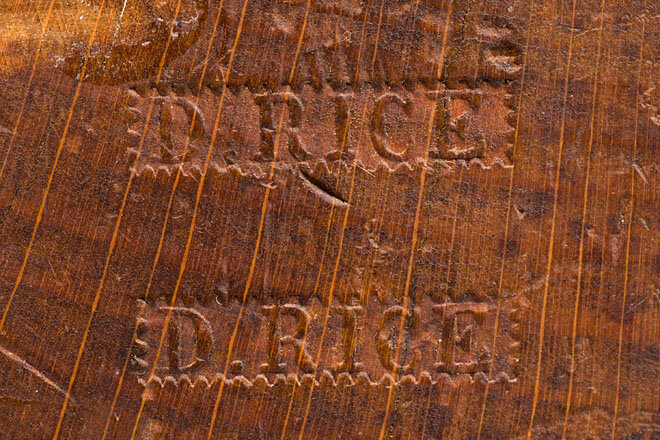

Worldwide Market

By 1850, railroad expansion enabled companies like Greenfield Tool Company (GTC) to ship their products to all parts of the United States, including ports where products were shipped overseas. This adjustable sash plane is imprinted with the GTC logo, “D. Rice,” and “For Chas & W.R. Stone, Muscatine – Iowa.” Hardware supply stores typically imprinted their name on the hand planes they sold. But how did it end up in Daniel Rice’s tool chest? On April 15, 1854, Charles and William R. Stone ran an ad for their hardware store in the Muscatine Journal. Six weeks later, a notice in the Muscatine TriWeekly Journal declared the Stones’ partnership had dissolved. The plane never shipped.

Objects:

To view an object, click on the photo. To see the object label information, hover over the picture with your mouse on a desktop computer or click the small diamond at the bottom right of the photo when viewing on a mobile device.

Deciphering the Marks on a Plane

Planemakers imprinted the company name on the toe (front) of the tool, and sizing information on the heel (back). Woodworkers who owned and used hand planes imprinted them with their first initial and last name, placement varied, and sometimes owner/users struck a tool with their name two or more times. A number on the heel of a plane indicates either the size of the element produced by the cut of the iron (blade), the thickness of the board for its intended use, or a model number.

To view an object, click on the photo. To see the object label information, hover over the picture with your mouse on a desktop computer or click the small diamond at the bottom right of the photo when viewing on a mobile device

Permanent Displays in Lobby

To view an object, click on the photo. To see the object label information, hover over the picture with your mouse on a desktop computer or click the small diamond at the bottom right of the photo when viewing on a mobile device.