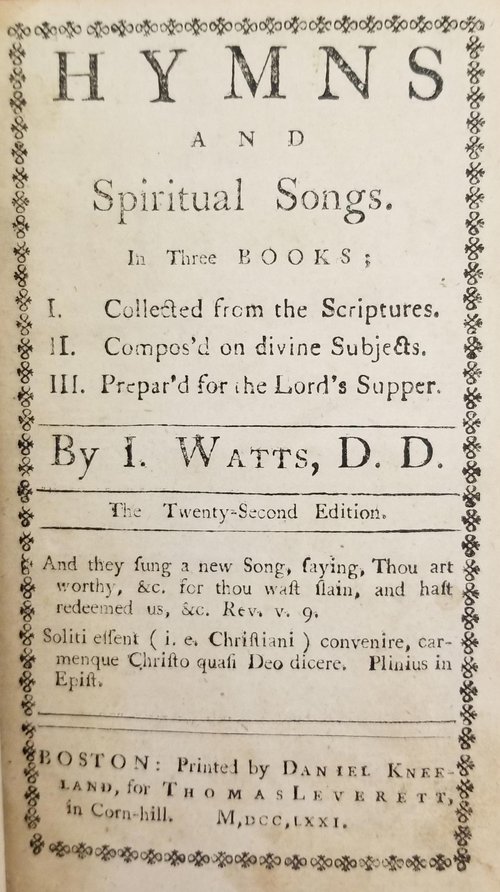

A recent library donation of rare books included the 22nd edition of “Hymns and Spiritual Songs” published in 1771. It joins six other hymnals written by Isaac Watts (1674-1748), an English Congregational minister and hymn writer (most notably “Joy to the World”), whose many hymnals were reprinted long after his death. Three in our collection boast a western Massachusetts provenance, with one owned by Ephraim Williams (1760-1835) of Deerfield, a testament to Watts’s enduring popularity and reach. However, the book’s uniqueness lies not in its nearly 300 pages of hymns or original ownership, but rather in its exterior.

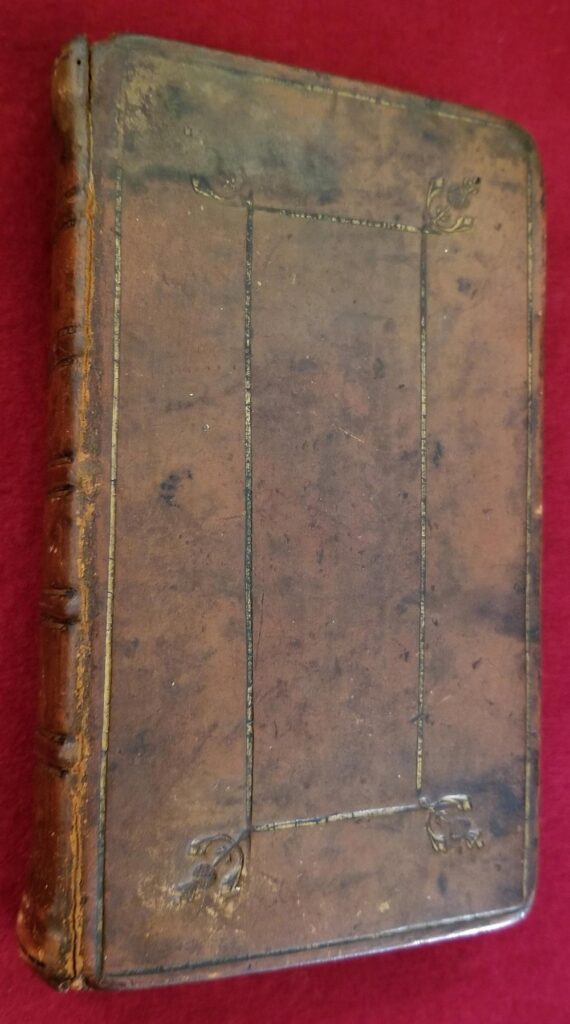

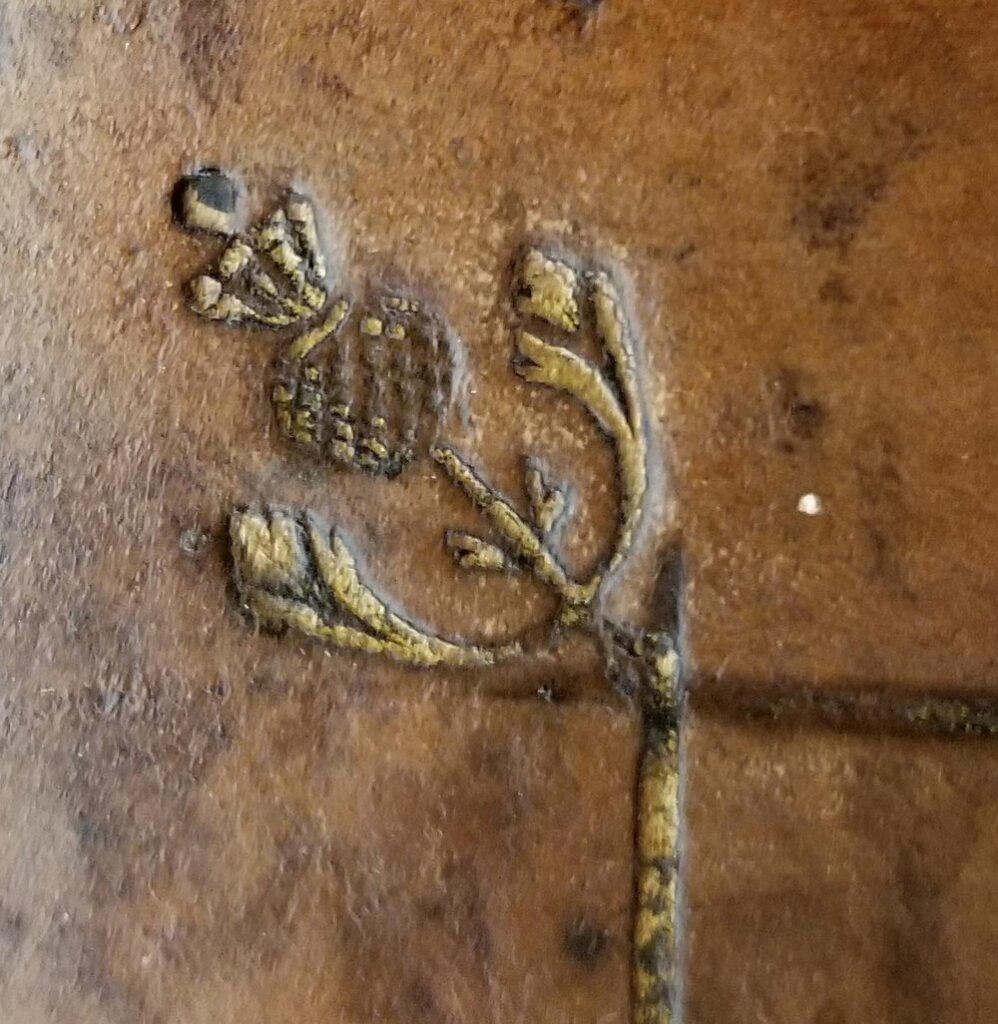

The book was bound in paneled leather, with a gilt-ruled border enclosing another gilt-ruled rectangle adorned with thistle and crown ornaments at each corner and five raised bands outlined in gilt on its spine. Although the gold has been somewhat rubbed away on its worn covers, this remarkably intact volume is a wonderful survival of a rare colonial binding. The use of gold is rather exceptional, for most contemporary colonial bindings featured blind-tooling if at all decorated, as the required expense and skill were beyond the capacity of most bookbinders. While its original owner is unknown, the book was clearly possessed by someone who valued and preserved the hymnal as a prized possession.

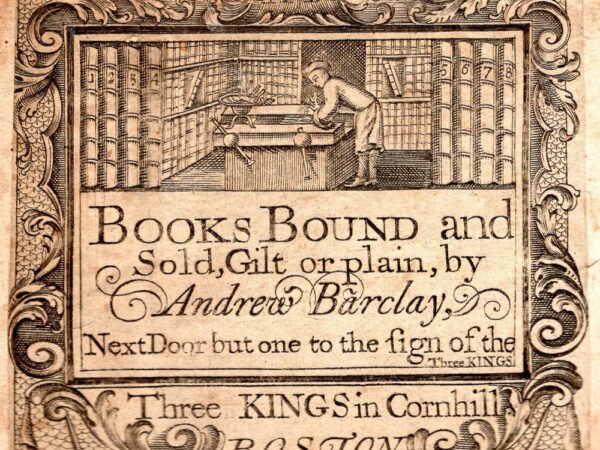

A bookbinder’s work remains largely anonymous unless an artisan stamped a name or initials onto covers or pasted a trade label inside. The thistle, the national flower of Scotland, connects this binding to one of a cohort of Scottish bookbinders who immigrated to Boston in the 1760s-1770s in search of new opportunities. An attribution has been made to Andrew Barclay, who arrived in Boston around 1760, based on stylistic similarities to a few known bindings with his trade label. This rare pictorial label depicts a bookbinder working at a press, a brazier full of gilding tools close at hand. Barclay advertised “Books Bound or Sold, Gilt or Plain,” with additional offerings of stationery supplies and books imported from London and Glasgow listed in newspaper notices. The breadth of books circulating through his shop encompassed Bibles and religious tracts, histories, reference works, primers, novels, and more. Such a combination of skills and revenue streams helped to keep many craftspeople afloat during fluctuating economic times.

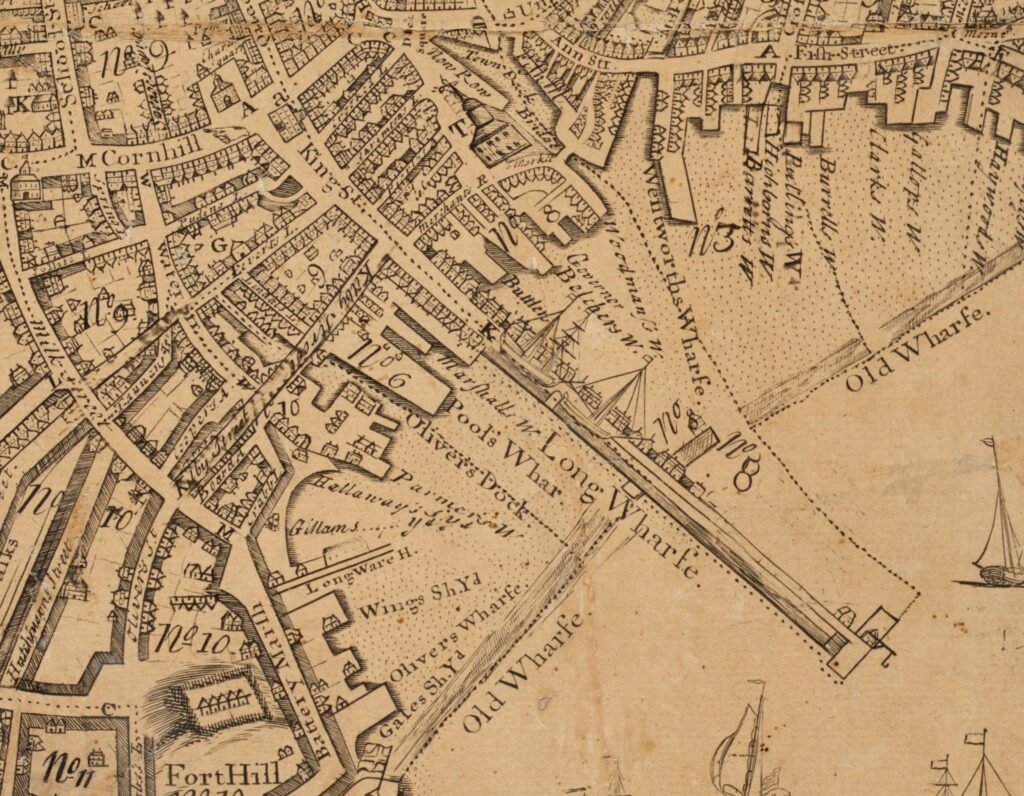

By 1770, Boston was the third largest city in the country, behind Philadelphia and New York City, with a population of over 15,000 residents. A high degree of literacy and a desire for printed material created an increased output, especially of newspapers, broadsides, and pamphlets in response to political unrest in the decades before the Revolution. Most material was either single sheets or multi-page items that needed only folding, stitching, or paper covers without a bookbinder’s expertise. The growing production caused a division of labor between printers and binders in the second half of the 18th century; earlier the two functions had been conjoined, although fluidity and versatility with skills still existed. Our volume demonstrates not only this skill separation but also the interdependence of artisans working in the printing and book trades during this time. The book was printed by Daniel Kneeland, son of printer Samuel Kneeland, for Thomas Leverett, who, like Barclay, was a bookseller, stationer, and binder. Based on newspaper ads and a greater number of imprints bearing his name, Leverett focused more on selling imported English goods and publishing books, with binding a somewhat occasional afterthought. It is unsurprising, then, that Kneeland would have handed the printed sheets off to binder Barclay to fold, gather, sew, cover, and decorate. All three men were conveniently located near each other on Cornhill, a commercial street teeming with tradespeople and merchants, one being Thomas Knight selling an even more dizzying array of imported goods than Leverett at the Sign of the Three Kings just two doors from Barclay. Cornhill was situated perpendicular to the Town House (now known as the Old State House), seat of the Massachusetts General Court at the head of King Street, a central artery flowing out of Long Wharf.

Despite finding a home in a new country, Barclay never fully assimilated and instead remained a staunch supporter of the Crown. He joined the Loyal North British Volunteers and evacuated Boston in March 1776 to eventually land in New York City where he operated a shop selling and binding books. At the end of the Revolution, he resettled in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, with other refugees and farmed on land received from the Crown to which he added more over time. Several compensation claims submitted for tools left behind and other losses in Boston were rejected. He may have bound a few books as new binding tools were itemized in his will; however, by this time he was past the peak of his career living in a more rural community with a smaller need for books. Barclay died in 1823 at the age of 86.

There remains much more to discover about colonial bookbinders – their work, their trade, and their lives. Fortunately, this volume provides another piece of the puzzle.