by Lea Stephenson, Luce Foundation Curatorial Fellow in American Paintings & Works on Paper

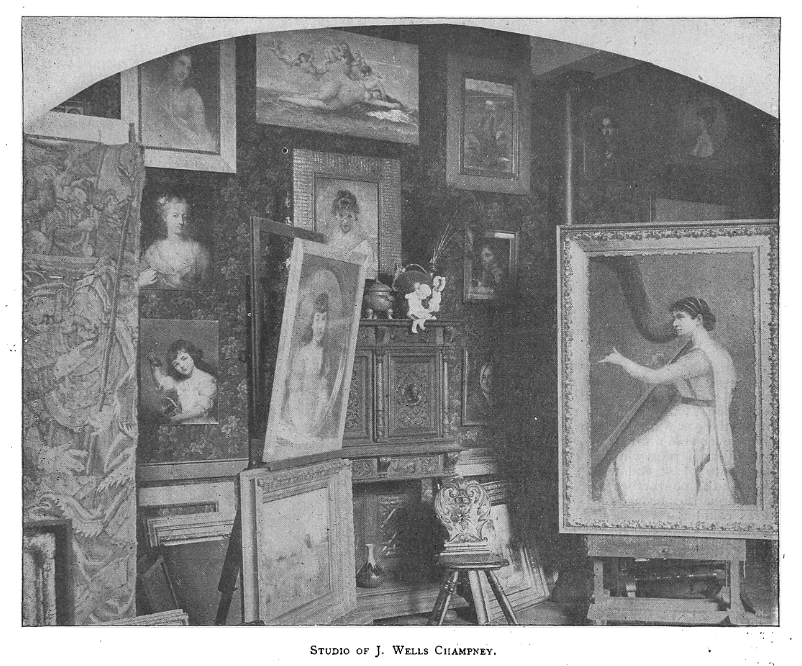

Imagine you are invited to a Saturday reception at the artist James Wells Champney’s New York studio. A sensorial atmosphere would greet you upon entering the apartment. Patterned textiles hang from the corners, against an array of rugs and textures on the floor. Canvases cover every available corner of the space—portraits of prominent New Yorkers alongside paintings of models in classical garb. An assemblage of decorative art lines the walls, whether objects tucked behind gilt frame mirrors or placed behind plaster busts on the mantel. The room showcases a medley of materials and forms.

Known today as one of Deerfield’s most important resident 19th-century artists, Champney split his time between the New England town and New York City. In 1879, he opened a studio in New York, first at 337 Fourth Avenue and then later moving to 96 Fifth Avenue (near Union Square). While Deerfield served as a space to engage with 18th-century material culture and the colonial past, New York offered Champney greater exhibition opportunities. When working in the city, he immersed himself in numerous art clubs, societies, and associations.

In his New York studio, Champney assembled an array of decorative art and props from different periods and cultures to create an “artful” interior.[1] Within this suite of rooms, he created a “Turkish corner,” a popular style in late 19th-century American interiors. These corners, and additional objects seen in Champney’s studio, drew upon Orientalism, a Western fascination with the “exotic” and the allure of the Middle East for European and Euro-American artists, often portraying the “East” as one of fantasy and decadence. Champney sectioned off this cozy corner with a curtain and canopy and included a lounge area with a couch covered by a rug, colorful cushions, an overhanging “mosque” lamp, and a carved “Moorish”-style chair. According to journalists, this room also included carved teakwood screens from India and latticed Cairo windows. Several paintings were installed on the walls, including portraits by Champney and a painting of Shakespeare’s Ophelia. Portfolios were propped against chairs, as if Champney had just consulted his reference material. Canvases leaned on easels to showcase the artist’s work to potential clients. Installed for its visual impact, this fusion of foreign and North American objects was intended by the artist to reflect his cosmopolitan taste. These interiors stimulated and dazzled the senses with the variety of textures, surfaces, and visual effects.

By the late 19th century, studios intrigued American audiences with their mystique of artistic creation and their opulent display of objects. This interest in studios coincided with the rising professionalism of fine art in the United States, made possible by new exhibition venues, museums, and art schools. An 1895 article on American artist studios described how audiences could catch a glimpse of “the studio life, of the atmosphere of art in which the painters live, and of their particular leanings and tastes, as shown by their surroundings.”[2] These interiors included both fine and decorative arts to create an aesthetic space that referenced the individual artist while also serving as a showroom. Elizabeth Williams Champney, a prolific author of fiction and Champney’s wife, wrote about the show studio and its eclectic collections “with rare bric a brac and artful effects of interior decoration.”[3] Interiors would often be filled with sumptuous textiles, decorative art, paintings, plaster sculpture, and foreign objects alongside the artist’s in-progress work. This calculated arrangement of collections became a form of interior decoration associated with American artists in urban environments.[4] Studios were a space to peer into the intimate lives of notable artists.

Like his contemporary William Merritt Chase, Champney organized aesthetically pleasing interiors that included his own artwork and drew upon various cultures and time periods. A “Moorish” chair appears frequently in photographs of the studio. Featuring distinct arabesque and sinuous floral decoration, the chair’s 19th-century style of decoration was based on the arts and architecture of Muslim inhabitants of north-west Africa and southern Spain. The elaborate style was connected to the fascination with Orientalism and exoticism, and also tied into colonialism and exploitation by Westerners. Champney likely acquired this chair in New York to augment the eclectic nature of his studio and complement his “Turkish corner.” Similar chairs designed by the American artist Lockwood de Forest were produced at the Ahmedabad Wood Carving Company in western India. Champney’s studio chair appears mass-produced, given the stamped numbers on the wood and machine-cut details.

This Fifth Avenue studio also featured a carved oak cabinet. In the mid to late 19th century, American interior decorators blended various historic styles. The cabinet was designed in the popular Renaissance Revival style, which involved ornate carvings reminiscent of objects from the 16th century. This example incorporated elaborate foliage, classical columns, pediments, and carved heads. Champney owned several Renaissance Revival furniture pieces, including a chair in Historic Deerfield’s collection, suggesting his interest in romanticizing history and European models.

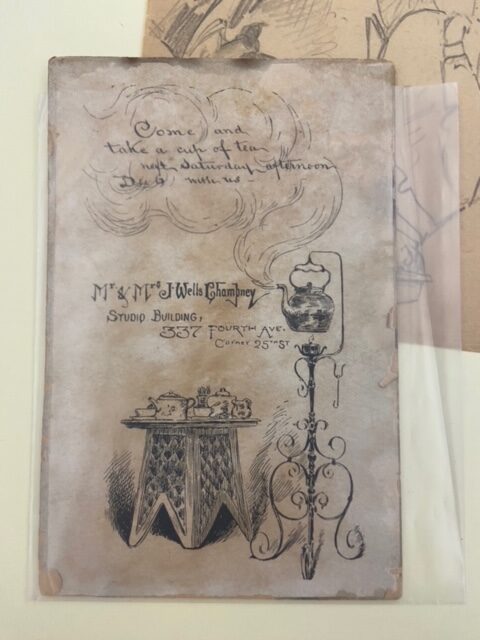

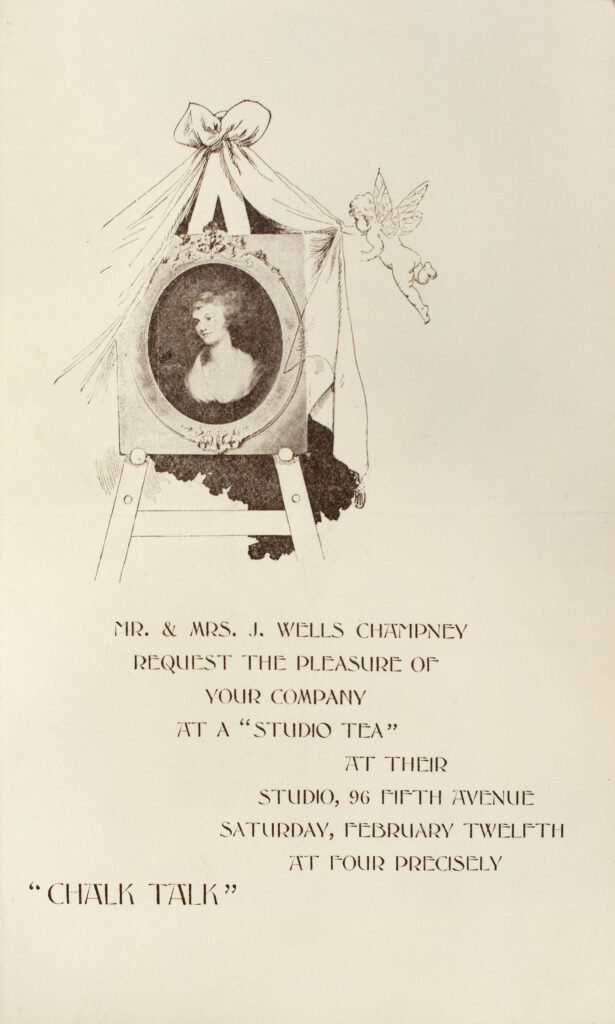

The New York studio and apartment of the Champneys served as a space for gatherings and social functions. James and Elizabeth Champney often hosted Saturday afternoon receptions at the studio. For a reception in his first Fourth Avenue New York studio, Champney designed an invitation with an alluring depiction of a Middle Eastern tabouret table and a steeping kettle. The rising smoke emphasizes the sinuous scrolls of the iron stand and fumes. Late 19th-century artists often relied upon receptions to lure prospective buyers. Studios were not solely rooms to be used for working, but also sites to showcase artistic production. Photographs of Champney’s New York space reveal his careful placement of pastels and oil paintings on easels as a way of utilizing the studio as an advertising room.

Why would Champney continually photograph his studio? We can think of our own tendency to record spaces and interiors. After decorating an interior, we often pride ourselves on the arrangement of objects that instill a space with a personal, aesthetic vision. Several copies of the studio photographs suggest that Champney wanted to document and preserve his artful arrangements–the ways in which he installed a series of canvases or layered materials alongside souvenirs from a trip abroad. While we cannot attend his Saturday receptions, the material culture left from the studio still carries the aura and mystique of the spaces Champney inhabited.

In Pursuit of the Picturesque: The Art of James Wells Champney is on view in the Flynt Center of Early New England Life until February 23, 2025.

[1] Isabel L. Taube, “William Merritt Chase’s Cosmopolitan Eclecticism,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 15, no. 3 (Autumn 2016), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2016.15.3.6.

[2] W.A. Cooper, “Artists In Their Studios,” Godey’s Magazine 130 (March 1895): 291.

[3] Elizabeth Champney also had her own writing space close to the studio. Lizzie W. Champney, “The Summer Haunts of American Artists,” Century Illustrated Magazine 30 (October 1885): 846.

[4] Sarah Burns, Inventing the Modern Artist: Art & Culture in Gilded Age America (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996), 50.