March 17, 2021 marks the 245th anniversary of the end of the Siege of Boston, which lasted from April 1775 to March 1776 during the early years of the American Revolution. The siege followed on the heels of the infamous battles at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts in April 1775. After obtaining intelligence that colonial militias had stockpiled military supplies in Concord, the British—then stationed in Boston under the command of General Thomas Gage (1718-1787)—marched into the Massachusetts countryside on the night of April 18, 1775 to seize and destroy the militia supplies. On their way to Concord, they passed through Lexington, where they skirmished with a group of militiamen on the town’s green early on the morning of April 19. Later the same day, they traveled to Concord where they confronted additional militia forces at Concord’s North Bridge, but were ultimately pushed back and sent retreating to Boston. Once the British contingent returned to Boston, colonial militias set siege to the city, which lasted for almost a year. The siege ended with the evacuation of British troops from Boston on March 17, 1776. Historic Deerfield is fortunate to possess several objects associated with the siege, including three engraved powder horns.

Throughout much of the 18th century, powder horns were a common accoutrement included among the kits of colonial militiamen. Made from the hollowed-out horns of cattle, they were ideal instruments for holding gunpowder due to their light weight and ability to keep gunpowder dry. In addition to carrying gunpowder, militiamen used the horns to prime or load their muskets. To do so, the user poured gunpowder out of the narrow tip of the horn into the barrel of the musket, and then emptied additional gunpowder into the pan of the musket. When the trigger was pulled, the flint mounted on the hammer struck the steel cover of the pan, igniting its contents and then the black powder in the barrel through a small hole. Owners transformed their powder horns into artwork when they ornamented them with their names and other designs. To achieve this decoration, the maker used a sharp tool to scratch the design into the surface of the horn, and then filled in the lines with a dark substance such as lamp black.

Several powder horns in Historic Deerfield’s collection possess inscriptions that document their creation during the siege. In fact, all three horns were made in Roxbury, Massachusetts, which borders Boston to the south. The inscriptions for each of the horns are listed below, along with images of each of the horns:

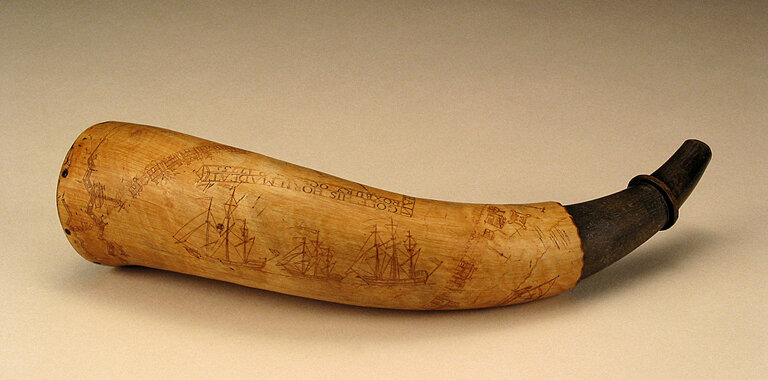

“Jonathan / Goff His Horn Made at / Roxbury Oct [illegible] AD 1775.”(Fig. 1)

“Jabez / Arnold / Oct. Ye. 1775 / Made [at] Rocks[bury] / Liberty. / His. Horne. / Liberty / Boston 1775 / Roxbury.” (Fig. 2)

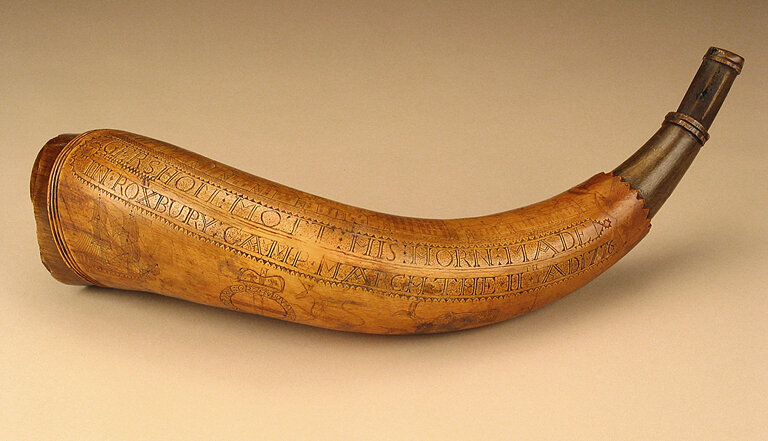

“Gearshom Mott His Horn Made / in Roxbury Camp March the 11th AD 1776 / Liberty or Death / Made in Roxbury / CP / Fort / Boston.” (Fig. 3)

Goff and Arnold both served as privates in Connecticut regiments during the early years of the war, while Mott served as a lieutenant colonel and captain in both New York regiments and Continental regiments throughout its duration. All three horns feature city views of Boston, and the Goff and Mott horns include depictions of fortifications surrounding Boston, thus providing further evidence of their creation during the period of the siege (Fig. 4). Though powder horns continued to be made by American soldiers following the siege, the frequency with which they were produced decreased following the early years of the Revolution due in part to the growing usage of cartridge boxes—leather carrying cases that held individually wrapped paper cartridges each containing gunpowder and a musket ball.