Clothing can often be a vessel for some of our most vivid memories. Garments can recall specific moments and important life events. Like the memories we cherish, saved clothing or its emblems preserves memory through tactile and visual senses. Martha Anna Abercrombie (1839-1923) of Lunenburg, Massachusetts, certainly tapped into this aspect of human nature when she assembled a swatch book of fabrics worn by her and her mother during the late 19th and early 20th centuries (fig. 1).[1] Donated to Historic Deerfield in 1969 by Martha Anna’s niece, Abercrombie’s preserved swatches record important moments ranging from a “first silk dress” to the colorful silk fabrics worn by her and other members of the family attending Harvard “class days.” Present as well are the more every day printed cottons from garments worn throughout her life. Taken as a whole, Abercrombie’s work provides important insight into fashion, memory, and daily life during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Swatch books, sometimes known as sewing diaries, are a well-documented way in which women recorded their clothing and the textiles they used.[2] Extant American examples dating from the mid to late nineteenth century, including Abercrombie’s, record clothes made by the women of the household, or in the case of more affluent individuals, by a dressmaker.[3] The recording impulse of these women shows just how valuable fabrics and clothing were, as well as the important role fashion played in their lives. More than just laborious documentation or sentimental records, these swatch books often showcase female artistic expression. Many of the pages are laid out with careful attention to color and texture, and some other sewing books contain sketches of garments[4].

Abercrombie’s work reveals that residents in Lunenburg, located in north-central Massachusetts, had access to many different kinds of textiles. The book contains assembled swatches of fabric used to create garments worn by Martha Anna, as well as those worn by her mother, Mrs. Otis Abercrombie (nee Dorothy Lovina Putnam, 1807-1886). Martha Anna assembled the book between 1890 and 1923, the year of her death. The pasted swatches are spread out among the 29-page booklet, which was assembled in hindsight as a record of past fashions, and not in real time as these fabrics were being purchased. Some pages display notations made in pencil, recording the date and/or use of the corresponding fabrics. The earliest written date for a fabric is 1850.

Of course, as a record largely after-the-fact, some errors may be present in the recording of specific details. But the collection of swatches allows us to study and engage with garments that no longer exist. These swatches give an idea of what fabrics a woman of her economic means was using to make her garments, as well as what textiles were readily available for purchase. This book also provides information on how often new clothes were made, and what sorts of occasions warranted new clothing. While much of the significance of the swatches is personal, they information they collectively yield is invaluable to scholars of material culture, connecting fashion to the larger historical narrative of the period.

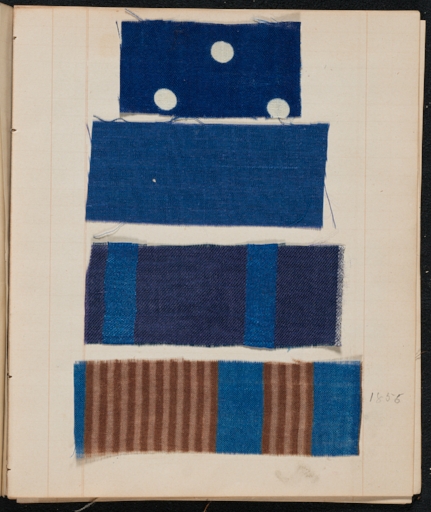

Most directly, the swatchbook chronicles fashionable colors and fabric types. A bright blue color, possibly achieved through synthetic dye, appears multiple times in the swatch book (fig. 2). Synthetic aniline dyes first appeared in the second half of the 1850s; their development allowed for much brighter and vibrantly colored textiles.[5] Early synthetic dyes were especially susceptible to fading; extant garments made from fabrics dyed in these colors (especially blue) usually exhibit muted or splotchy hues from the deterioration of both fabric and dye as a result of cumulative exposure to light and environmental pollution. Because they have been protected in the book, however, the swatches dyed with the synthetic blue retain much of their original color, acting as a valuable visual resource for imagining what these fabrics looked like when new.

Several extant, colored fashion plates from the 1860s also feature the bright blue color in dresses and accessories (fig. 3). While most fashion plates at the time were hand-colored, the presence of numerous examples with similar shades of blue suggest a popularity for novel, bright aniline dyes in fashionable dress.[6] Such a vibrant silk fabric was used for a “class day” dress, worn by Martha in 1866.

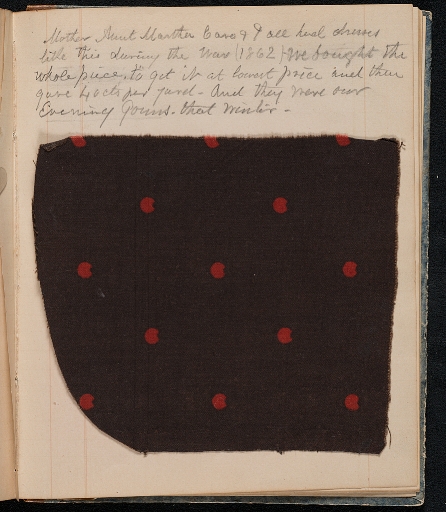

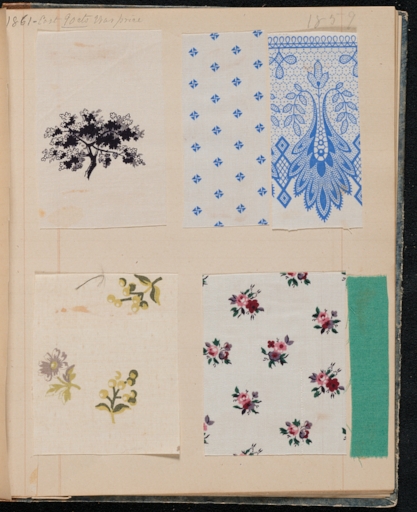

This swatch book also connects its maker to the Civil War. The swatch on page 22 features a woven black cotton (now faded to brown) decorated with red spots, was purchased for “40 cts per yard” (fig. 4). Abercrombie notes the fabric’s employment to make the evening dresses she and the women of her family wore that winter. She also remarks that the whole length of cloth was bought to get the best price, and that several women in her family had dresses made from it “during the war”. The Civil War is mentioned again (dated a year before, 1861) on the next page (fig. 5). Here is affixed a cotton fabric with a printed tree motif, bought at “9cts War Price”. Cotton would have been an unusual choice for an evening gown, with silk being preferred for its smooth texture and luster. This choice of fabric for evening wear, when compared with the recorded silk fabrics used for day dresses in earlier years, demonstrates the impact of the war on the availability of occasion-specific fabric, and highlights the changes in lifestyle and spending that became necessary in wartime, despite being geographically far removed from military action.

It is easy to see why Martha highlighted these particular textiles within the book, given the enormous presence of the Civil War in daily life and the emotional and physical scars it left on much of the American population. The notations reveal a strong memory of such a tumultuous time. The Civil War references are, coincidentally, the only two in the book where cost is noted, suggesting the economic impact the war had on her everyday life. The cotton embargo of 1861 and Union blockades of Confederate ports greatly reduced the flow of raw cotton to the manufacturing centers of Britain, raising tensions and the question of British military involvement[7]. Although meager, the two references reflect issues of global trade and manufacturing during times of crisis, and the effects on the lives of everyday people.

Clearly, Abercrombie cared about fashion. Turning again to fashion plates, we can compare the spotted cotton used for the war time evening dresses with a spotted gown from an 1860 American fashion plate (fig. 6). Similarly, a textile with a crinkled texture, found on several pages of the swatch book, resembles an illustrated textile (possibly moiréd) seen in an 1859 fashion plate (fig. 7). On a page containing fabrics from 1858 “class day” dresses, the compiler included a sample of the purple and white trim used on a green, white, and purple striped silk dress (fig. 8). A fashion plate from 1851 (fig. 9) shows a similar combination of colors, and perhaps a suggestion of how the trim was used on the gown. While there is no way of truly knowing what Martha’s garments actually looked like, the combination of the swatch book and fashion plates suggest an awareness and ability to incorporate stylish dress fabric patterns into her own wardrobe, even if they were not of the most refined textiles.

While this swatch book is by no means explicit in its description of clothing and fashion, as well as in its links to larger themes and issues, the subtle details included by the compiler can provide clues as to how her own connection to the events of history was preserved in her memory through her clothes. Through her swatches, we can see hints of the changing fashions, new technology, and the effect of large historical events such as the Civil War. This colorful record of a woman’s wardrobe is a tangible link to the past and a potent reminder of the importance and emotional power clothes held, and continue to hold, in our lives.

[1] Historic Deerfield, Gift of Mrs. Lewis Merriam (Alice Abercrombie Merriam), V.050.

[2] An important, early example is the swatch book and clothing diary of Barbara Johnson, an English woman born in 1738 who painstakingly recorded the yardage, cost and use of the fabric she purchased. See Natalie Rothstein, ed. A Lady of Fashion: Barbara Johnsons Album of Style and Fabrics (London: Thames and Hudson, 1987).

[3] For other American examples, see Susan W. Greene, Wearable Prints, 1760-1860: History, Materials, and Mechanics (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2014), 10; Karen J. Herbaugh, “Needles and Pens: The Sewing Diaries of American Women, 1890-1920,” The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings 1(2006/2007), printed 2009: 95.

[4] Ibid., 98

[5] Greene, “Wearable Prints”, 200-201.

[6] Joan L. Severa, Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion, 1840-1900 (Kent, OH: Kent State Univ. Press, 1995), 196.

[7] Sven Beckert. “Emancipation and Empire: Reconstructing the Worldwide Web of Cotton Production in the Age of the American Civil War.” The American Historical Review 109, no. 5 (2004): 1405-438. 1410