Created by Museum Education and Interpretation Department staff members Faith Deering and Claire Carlson

Welcome to the 15th installment of Maker Mondays. During July and August, we will be posting these activities twice a month. Check your social media feed or look for an email from us on Monday, August 3, for the next fun activity that you can do at home, inspired by history and the Historic Deerfield collections, using common household items.

Download a printable version of this activity (PDF).

This Monday we’re encouraging you to create your own paper powder horn. We will show you some examples from The William H. Guthman Collection of American Powder Horns at Historic Deerfield, offer a brief description of how a powder horn is made, and then guide you in making your own paper powder horn.

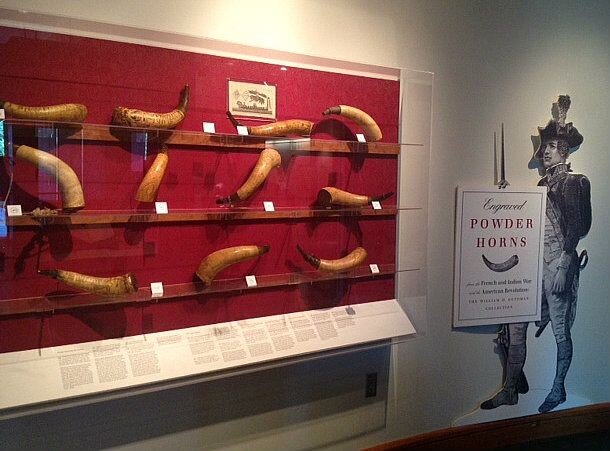

A selection of some of the powder horns from The William H. Guthman collection on display in the Flynt Center of Early New England Life.

A powder horn is a powerful and poignant piece of folk art. Holding the black powder needed to fire a musket, the powder horn was a personal piece of equipment, worn close to the body, and adorned with hand-carved images and personalized with the wearer’s name. The William H. Guthman Collection of American Powder Horns includes 75 horns, most of them dating to the French and Indian War (1754-1763) and the American Revolution.

A highlight of the collection is the horn owned by Israel Putnam of Revolutionary War fame who is thought to be the one who declared “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes” at the Battle of Bunker Hill. His powder horn dates to the French and Indian War and identified him as a captain and includes a “plan of the Stations/ From Albony to/ Lake George/ The River, The Road.” And it is also inscribed “Capt. Israel Putnam’s Horn made at/ Fort wm, Henry Novr, the 10th AD: 1756”. Powder horns such as these serve as unique objects because they can include the date, name, place and personal information of individual soldiers and events. Phil Zea (2008: see bibliography below) writes, “They are simultaneously rare documents of history and expressions of emotions while arguably, on the aesthetic side, one of the few indigenous art forms of colonial America.”

Israel Putnam’s Powder Horn. Side One. HD 2005.20.9

Israel Putnam’s Powder Horn, Side Two. HD 2005.20.9

Another important aspect of the Guthman Collection of Powder Horns is that it is a comprehensive set of engraved powder horns spanning the years between 1747 and 1781. In this collection, we can see the beginnings of this art form and how it developed over the decades of the various colonial wars. Some of the powder horns were signed by the carvers themselves and some of them would have been made by the individual owners. The Guthman Collection has powder horns that were carved by master carvers such as Jacob Gay, Samuel Lounsbury, and John Bush. Some of the horns carved by Gay are marked “J.G.,” while others are attributed to carvers based on distinctive stylistic elements.

One of the most beautiful powder horns in the collection is attributed to John Bush, a master carver who influenced later carvers such as Samuel Lounsbury, Nathaniel Selkrieg, “JW,” and “Memento Mori.” The little we know about John Bush is that he was a free Black man from Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, who worked for only a few years before his capture on August 9, 1757. Bush’s connection to Deerfield is the beautiful powder horn that he carved for William Williams Jr. which is characterized by highly stylized capital letters, graceful scrolls, and borders and decorations of feather-like shells and flowers. This powder horn dates to 1755 when Williams was a Surgeon’s Mate during the 1755 Lake George campaign under his uncle, Dr. Thomas Williams of Deerfield.

William Williams Jr. Powder Horn attributed to the carver John Bush. Side One. HD 2005.20.6

William Wiliams Jr. Powder Horn, Side Two. Note the whimsical decorations on this side. HD 2005.20.6

Close-Up Detail of the William Williams Jr Powder Horn. Note the graceful letter “W” and the swirls on the left side of the letters “I and L.” HD 2005.20.6

Other powder horns in the Guthman Collection show the artistry, skill, and sense of humor of both the carvers and the wearers. Below are some fun examples:

This detail from William Paterson’s powder horn made in 1759 shows a ship sailing among a school of fish, and beautiful border work with dots, diamonds and scrolls. HD 2005.20.37

This horn by Jacob Gay represents his best work and is doubly important for depicting an historical scene, the Boston Massacre, a rarity on powder horns. The scene is adapted from an engraving of the Boston Massacre (HD 0864) produced by both Paul Revere (1734-1818) and Henry Pelham (1749-1806) in 1770; the scene is reversed, and the men depicted assume the satiric theatrics of most of Gay’s creatures. This horn was made in 1772 for Hamilton Davidson. HD 2005.20.44

This beautifully carved powderhorn depicts Fort William Henry done in a 3″ square plan that shows a large British flag flying from a tall staff. The detailed plan even includes the staircases visible through the windows of the barracks. It is the powder horn of Thomas Smith Diamond and was made in 1756. HD 2005.20.10

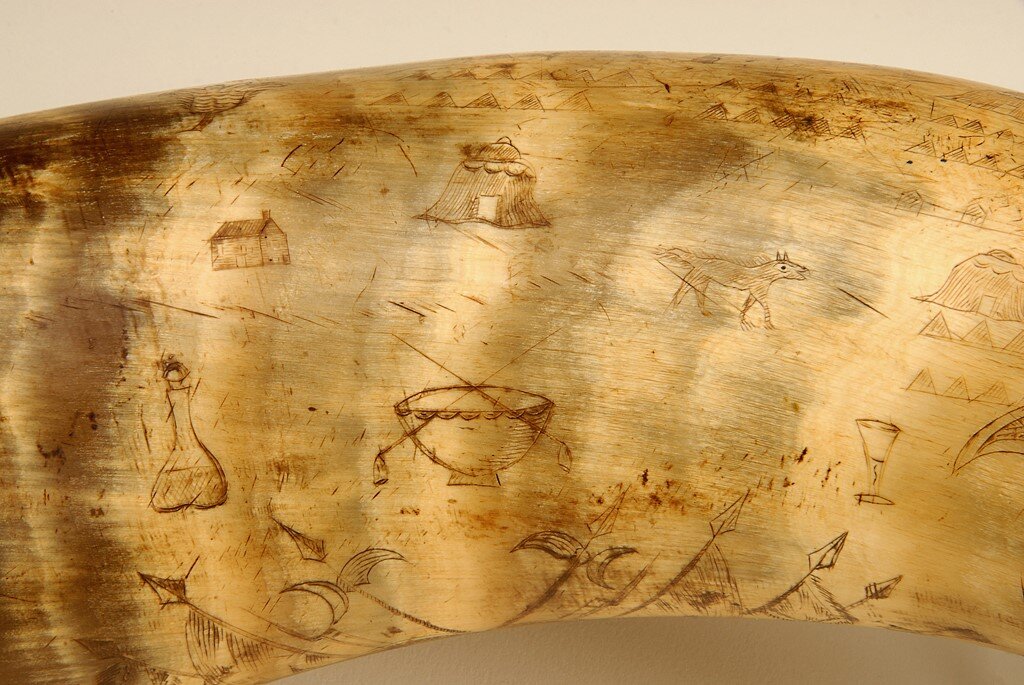

This powder horn has images of daily life sprinkled across the back side: tobacco pipes, a punch bowl, a tent, wine bottle, drinking glass and a dog are shown among other doodles in this whimsical example. HD 2005.20.20

What is a powder horn?

We have shown you some wonderful examples of carved powder horns from the Guthman Collection But, really, what is a powder horn? It is a container used for storing gunpowder. They were made (powder horns are still being made today by crafts people who have studied this historic trade) from hollowed out cattle horns. Gun powder must be kept dry; and the horn of a cow makes a perfect durable, waterproof container. The curved shape of the horn created a natural funnel for pouring gunpowder into a rifle.

In a time when cattle were common on the frontier, it was easy to obtain a horn from a slaughtered cow or ox. Animal horn is a natural bone-like material called keratin. Your fingernails are keratin, smooth and hard just like horn. n order to begin the process of making it into a container, the horn must be cleaned and hollowed. Once the interior was clean and dry, the outer surface was scraped, polished and trimmed on both ends. A hole was bored into the pointed tip to connect it with the inner cavity. Next, a wooden plug was whittled to fit the wide end of the horn and tacked permanently into place with small nails. The horn was filled with gunpowder through the drilled hole at the narrow end, which was also plugged with a wooden cap. The final step was to attach a leather cord to each end of the horn, thus making it possible for the powder horn to be slung over a shoulder for easy access.

Historic Deerfield Guide, Peter King, shows Education Program Coordinator Claire Carlson the tools used in creating a carved powder horn.

Powder horns did keep gunpowder dry and readily available for use. In addition to serving as a perfect storage container, the smooth rounded surface of the horn was seen as an excellent place to carve. The design was carved into the horn using a small knife and then ink or soot was rubbed into the design to darken the images. Some soldiers would personalize their own powder horns by etching their name, date of carving, location of carving, as well as maps, etchings of forts, coats of arms, animals and people. Some carvings were purely whimsical while others contained battle information and memories of war campaigns. Many powder horns were elaborately decorated by men who became experts and recognized as professional carvers. So unique was their carving that the powder horns they worked on can still be recognized and attributed to these masters as discussed above.

Most powder horns were being made and carved between 1746 to 1780, during the years of the French and Indian War and later, the American Revolution, along the frontier of northern New England, upper New York State, the eastern Great Lakes and Canada.

Engraved powder horns offer a wealth of information about the realities of war and everyday life in Colonial America. They are important for the great historical information they offer as well as being significant as an indigenous art form. As Zea noted, “…very few artifacts whose purpose is dominantly functional become simultaneously a kind of personal scrapbook on something as primas and poignant in society as the ironies of war. Rather than capturing time in a bottle powder horns capture what mattered most to a soldier at a personal level and at a given time and place.”

Make a Paper Powder Horn

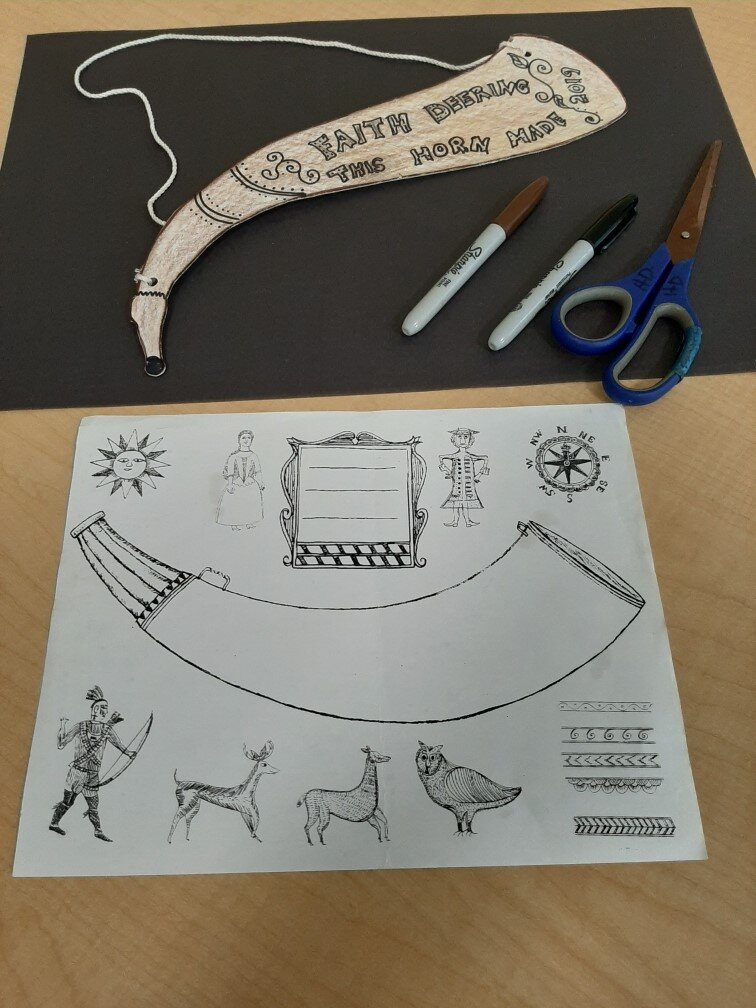

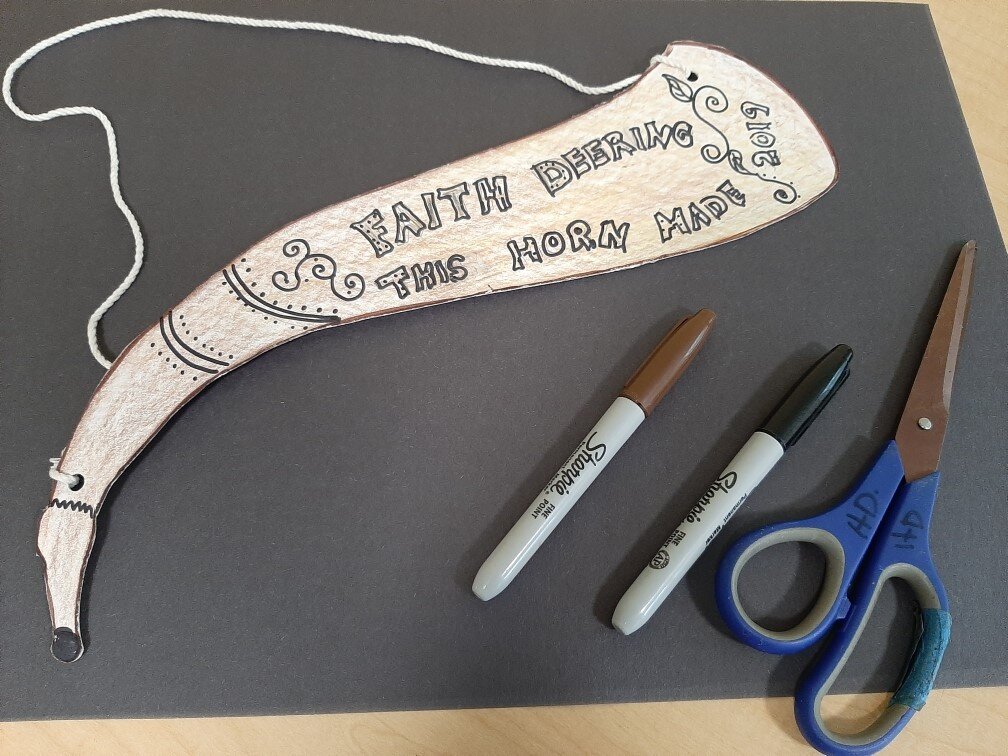

Now that you have learned about the history of powder horns, and seen some beautiful examples from Historic Deerfield’s collection you can try your hand at making a paper powder horn. Although it won’t keep your powder dry, it will give you a chance to be creative and personalize your own piece of American folk art. We have provided a horn-shaped template for you to decorate and cut out. Click on this link for a PDF of the template for you to print at home.

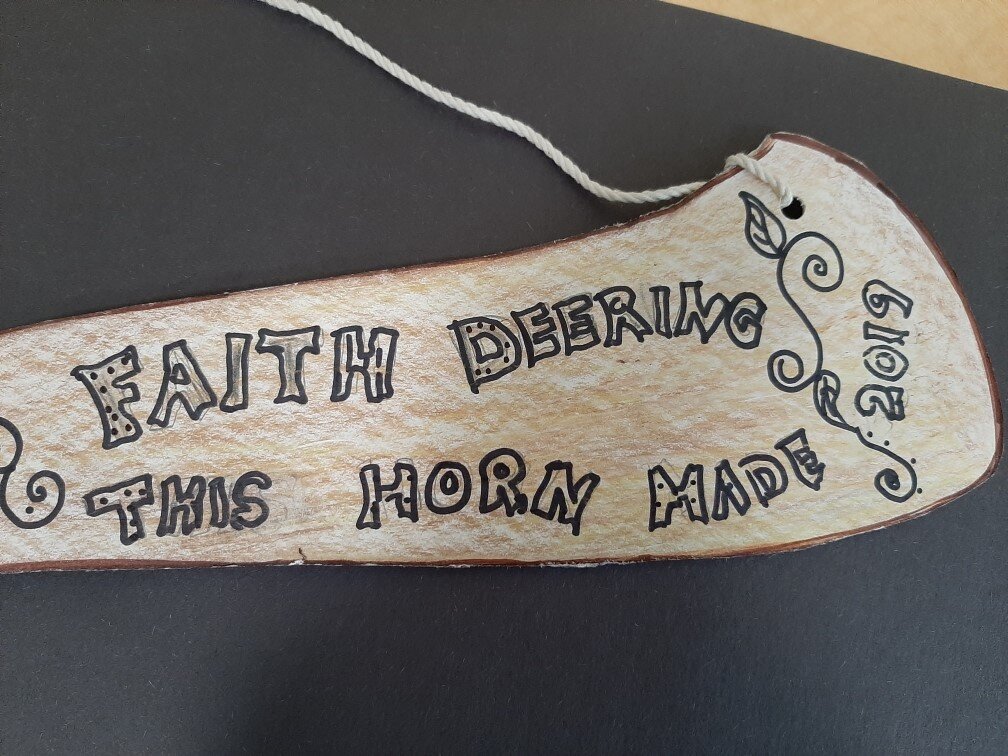

We suggest planning your design and drawing it with a pencil, then tracing over it with a fine-point black marker. You can use this as a model, or trace your own onto a piece of card stock or manilla file folder. When we offered powder horns as an activity in the History Workshop, visitors could choose to make a larger, more durable version from cardstock. You can see our sample that has been strung with a cord so it could be carried over the shoulder.

As you think about the way you will engrave (decorate) your powder horn, keep in mind the very personal aspects of the powder horns in the images we have shown you. Most important would be the name (or initials) of the owner and the engraver. Next, would be the date of engraving and, often, the location where it was made. Rhymes, mottos, maps, landmarks and significant events were carved into the horn. Some images engraved on the horn were whimsical, flowery and very decorative. Very popular were human figures, animals, and flowers, images that reminded the carver of home. Have fun and imagine yourself carving on real horn, creating a beautiful, functional object— the horn that would keep your gunpowder dry!

Resources:

To search the collections database for more information about the powder horns please use this link: http://museums.fivecolleges.edu/info.php?s=HD+2005.20&type=all&museum=hd&t=objects

Interested in learning more about powder horns? Explore these resources:

https://www.shrewsburyhistoricalsociety.org/engraving

https://www.historic-deerfield.org/powder-horns

Click the link below for a PDF of the article: Revealing the Culture of Conflict: Engraved Powder Horns from the French and Indian War, written by Historic Deerfield President Philip Zea: Revealing the Culture of Conflict.pdf

Guthman, William H. Drums A’beating, Trumpets Sounding: Artistically Carved Powder Horns in the Provincial Manner, 1746-1781 (Hartford: The Connecticut Historical Society, 1993).

Lee Larkin at Work. A photo essay in: Historic Deerfield Magazine, Volume 9, Number 1. 2008. Special issue focused on the French and Indian War.

We would love to see a photo of your finished powder horn. Send it to us at historicdeerfield@historic-deerfield.org. In return we will mail you a beautiful Deerfield powder horn postcard. Include your mailing address if you would like to receive this special card.

This Maker Mondays blog is dedicated to the memory of Peter King, a member of the guiding staff who passed away in December 2019. He loved to share his love of history and powder horns with our visitors. Here he is showing his work to a young visitor in 2012.