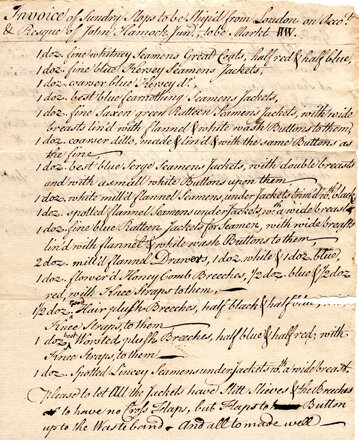

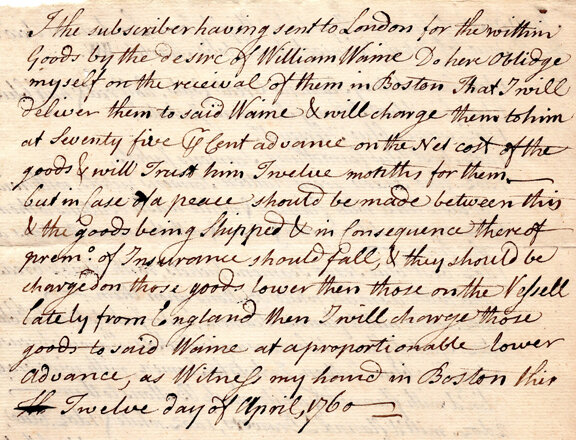

Figs. 1 and 2: “Invoice of Sundry Slops to be Ship’d from London…” 1760. Memorial Libraries, Historic Deerfield.

This fascinating document outlines a shipment of ready-made clothing sent from London to Boston merchant tailor William Waine in 1760, at the height of the Seven Years’ War. In total, it describes 176 garments, in sets of 6, 12, and 24, including greatcoats (outer overcoats), jackets, underjackets, drawers (underwear), and breeches (knee-length legwear). They would be packed in containers marked with Waine’s initials. A Boston merchant, John Hamock, outlined the inventory and the nature of the bargain: he had ordered these goods from London at Waine’s request and planned to provide them to Waine, essentially on consignment, for a year. If the war ended soon and insurance premiums fell, Hamock would pass those savings on to Waine. What can this document tell us about clothing in Boston in the middle of the 18th century?

William Waine was born in about 1724, probably in Boston, and likely apprenticed as a young man in the town. In the early years of his career, like most other tailors of the age, he worked entirely on “bespoke” or custom garments for men. Almost everyone in the early and middle years of the 18th century wore garments that were cut and sewn to their precise body shape and dimensions. Because there were many tailors – it was the most common occupation in cities – and their labor was cheap, even common workers could afford this sort of clothing. It was the material of your suit – not that it had been custom-made – that marked your level of social refinement. But this inventory reminds us that there was another path: the growing trade in ready-made garments.

As the century wore on, ambitious tradesmen in western Europe and Euro-America began to produce ready-made clothing for off-the-rack sales. New categories emerged. “Slops” meant ready-made garments, and slop sellers and slop shops focused almost entirely on these garments, selling primarily to transient sailors and other poor workers. Meanwhile, “merchant tailors” presented a slightly more refined face, continuing to make some bespoke clothing but also producing and importing ready-made garments. According to his business papers, William Waine gradually transitioned to something more like a clothing dealer – a merchant tailor – from his earlier work in the bespoke trade. His shop would have looked more like what we would expect to see today in a clothing store – albeit almost certainly with some production space – and less like the busy workshops of other tailors.

Though he did it earlier than most, Waine was not entirely unique in this transition. What sets him apart, however, is the survival of archival material that documents his work, including this invoice in as well as papers at Stanford University Libraries and the American Antiquarian Society. While many merchant tailors sprang up in American cities in the 1790s and early 1800s – men who left slightly larger paper trails – we have very few references to how the ready-made garment trade functioned in earlier years. This makes the Memorial Libraries’ invoice and Waine’s complementary accounts an unparalleled archive for understanding this trade and the people involved.

Merchant tailoring was never a particularly lucrative trade for Waine. There was almost as little profit margin in ready-made clothing as there was in bespoke clothing, and there was plenty of competition. Waine, for example, never owned any of the real estate he occupied: he rented various shops for decades. He used merchants such as John Hamock (in the case of this receipt) and John Hancock as intermediaries in his trans-Atlantic orders because he lacked the capital and the vessels needed to conduct that leg of the business.

But his business was successful enough for Waine to climb slightly higher than most of the common tailors of Boston. He maintained a family that included his wife and at least four children, and he acquired several horses. In 1763, he purchased an enslaved boy for more than 28 pounds, a young man who remained unnamed in Waine’s accounts but who might have himself learned the tailoring trade in Waine’s shop. He maintained some level of economic stability until his death in 1786, aged 82, just three months after his wife, Mary. The incident merited only a single line in Boston’s newspapers. Among the papers sitting in a box in his home – papers that were almost inexplicably well preserved by future generations – was probably the double-sided invoice from 26 years before, the one now in the Memorial Libraries.

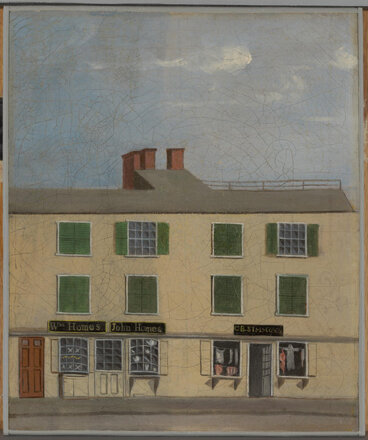

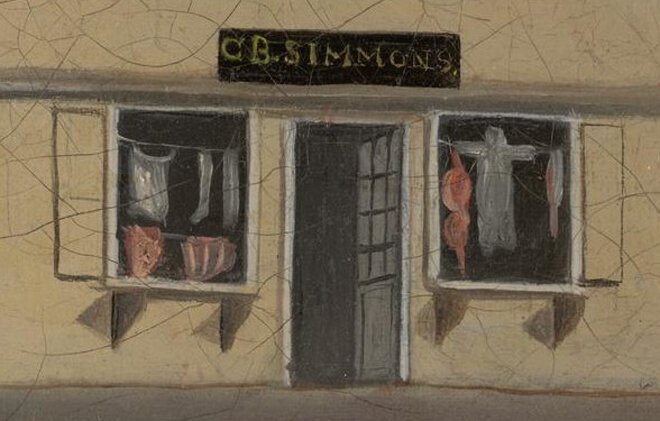

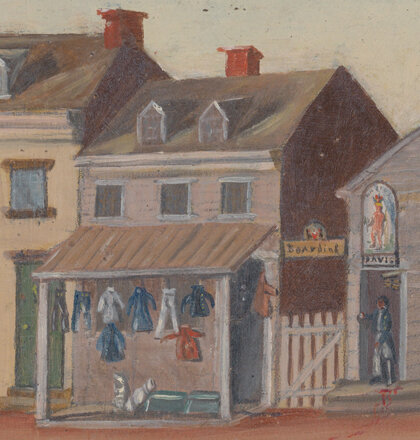

This particular 1760 invoice provides us with an exciting glimpse into the sort of garments that Hamock and Waine thought would appeal to Waine’s waterfront customers. It would be a mistake to imagine these sailors as wearing plain clothing. Sailors dressed to suit the fashions of the day but also according to styles that were sometimes distinctive to their trade. Imagine one of them walking into Waine’s shop in 1760, his pocketbook heavy with the pay he received for a wartime voyage when his labor could command high wages. Perhaps he was enticed in by garments hung up for eye-catching display, as they are in depictions of the shops of Boston slops-seller Cornelius Simmons and New York clothing dealer Jacob Abrahams from a generation later.

Figs. 4 and 5 These images shows the ready-made clothing shop of Cornelius Simmons on Ann Street, Boston, between 1816 and 1825. Unknown, “The Silversmith Shop of William Homes, Jr.,” Yale University Art Gallery.

Fig. 6 This detail from a larger image shows the ready-made clothing store of Jacob Abrahams at 360 Water Street in New York City about 1813. Detail, William P. Chappel, “The Dog Killer,” The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps, and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Viewing Hamock’s consignment, likely displayed on pegs and shelves around Waine’s shops, our sailor would have much to choose from. Of course he needed a new jacket, but what to choose? One of “best blue fearnothing,” a fabric with a thick pile that kept you warm and shed water? Or perhaps one of “fine blue Ratteen” (another thick fabric) with “wide breasts lin’d with flannel & white wash Buttons”? And for his breeches? He might wear trousers (legwear that reached down to the ankle like pants today) for some work tasks, but like most men he still favored breeches (which went down just past the knee and fit snugly and were worn over stockings that flattered the leg). And here in Waine’s shop the choices were dizzying. Would he choose blue, red, and black “plush” velvet breeches? Or was he even more daring? Perhaps his eye was drawn to the blue and red “flower’d Honey Comb Breeches,” which were made from a velvet but also featured a printed pattern. Walking out onto the streets of Boston on that day in 1760, there was a new spring in his step. As William Waine watched from inside the shop, the sailor turned the corner, and both men disappeared into history.

Tyler Rudd Putman is the Gallery Interpretation Manager at the Museum of the American Revolution and holds a PhD in the History of American Civilization from the University of Delaware. Henry Cooke is an independent researcher and historian, and the principal of Historical Costume Services in Randolph, Massachusetts. He holds a BA and MA in History from Tufts University. Henry will demonstrate his tailoring skills during Historic Deerfield’s historic trades series on Saturday, September 25, 2021.