by J. Ritchie Garrison, Professor Emeritus of History, University of Delaware

One of the most remarkable historic features of Deerfield, Massachusetts is the survival of the common fields on the meadows surrounding the original English village. The Meadows’ fertility has served the needs of human occupants for thousands of years, although the strategies for planting and harvesting changed as English settlers occupied the raised terraces on the eastern and western sides of the Meadows. Preserving the open agricultural fields is a high priority for Historic Deerfield, the Franklin County Land Trust, and the families that still farm the area.

Geographers have drawn parallels between the Connecticut River Valley’s common fields and those in medieval England, but there were important differences. In England, Manor Lords owned the land; tenants farming that land paid rent. Deerfield families who owned the Meadows had to manage the land cooperatively. Individual settlers who held shares in the Deerfield Meadows could sell or rent their fields, but their farming practices and the land itself, restricted how they used their property.

The Meadows—south, west, and north—varied somewhat in topography and layout. Some areas were marshy or suited to wet meadows. Others were somewhat higher and ideal for tillage fields. Early surveys of the North Meadows, such as the 1837 Boutelle survey, show a high percentage of long narrow fields oriented to the northwest, but there were also rectangular lots in the lowlands near the river (Fig. 1). The long fields associated with tillage addressed the realities of animal traction and the challenges of turning plows and animals around at the end of a long furrow. Hay fields and pasture were likely to be more irregular or oblong, configurations that were useful for mixed farming based on hand tools, animal husbandry, and grains.

The first range of the Common-Field fence, constructed after 1683, began at Cheapside (now a part of Greenfield), ran south to “the Street” (present-day Old Main St.) where it turned to encompass the west side of the town’s homelots, turned again at the edge of the South Meadows, and continued south to the rear of the Wapping homelots. At that point, the fence ran west at “Boggy Meadows” to the “Bars” where the road to Hatfield was located, and thence south of Stebbins Meadow to Stillwater where it joined the Deerfield River (then known as the Pocumtuck River), a distance of about 7 miles. The river proved ineffective as a barrier to animals. Before 1692, owners added a second range of fencing to enclose the meadows on the west and north sides of the River at Wisdom and Cheapside—approximately another 7 miles. Each year, owners appointed two fence viewers to ensure the Common-Field fence was kept in good order.

Animals were a persistent problem for resource management. Deerfield’s Meadows were too valuable to set off individual lots with fencing. Similarly, cartways were quite narrow to maximize planting space. Chickens, milk cows, and working oxen were held in fenced areas of Deerfield’s homelots or nearby on hillside pastures. As contiguous hill towns developed in 1760s, Deerfield farmers sometimes sent steers to rented pastures in the uplands during prime growing seasons. In the late fall, they opened the common fields to let animals graze on leftover fodder before fattening cattle in stalls for sale in the Spring.

Sheep and pigs presented a different set of problems. Sheep were vulnerable to predators and would eat grasses to their roots unless moved at intervals. Before the American Revolution, few Deerfield families owned sheep, although the size of flocks increased during wartime shortages. Pigs were tough enough to fend for themselves browsing outside the Meadows, but, like bovines, they could break through fences to eat or trample meadow crops. Owners of livestock that invaded the Meadows were subject to fines, damages, and impoundment fees.

Deerfield’s Proprietors of the Common Fields supervised the construction and maintenance of fences around the Meadows. Wood fences were practical solutions as the Meadows are nearly stone free. Most were made of posts and rails, with the split posts rising approximately 4-5 feet above grade; the rails were split from logs of about 10 feet in length, with 4 rails per section apparently the norm. Workers drilled each post with an auger where the rail mortises were located and chopped out the sections between the auger holes; then the rail ends were tapered with an axe to allow the rails to be set into the mortises as the posts were inserted into the ground.

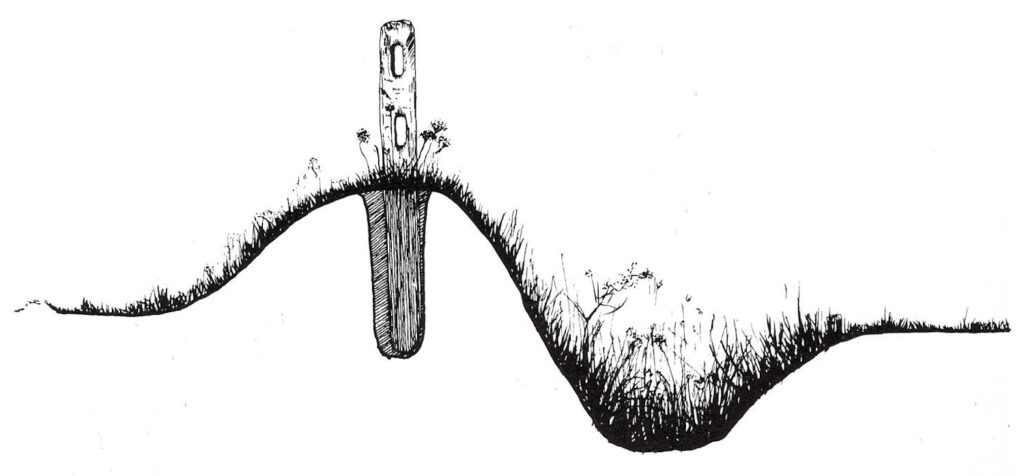

On some sections of the fence, proprietors employed ditch-and-rail fencing. Workers dug a trench, pitching dirt to one side to form a mound. Atop the mound, they set 2-rail sections of post-and-rail fencing (Fig 2). The mounds grew slippery with grasses and weeds that held the soil. If the ditch silted up, owners excavated. The combination of ditch, mound, and rails created a barrier roughly 5-6 feet high and too wide for livestock to leap over.

The common field fence had gaps where roads were located. The one at “the Bars,” referred to removable poles, set on ledgers attached to two posts on each side of the road with a small gap between them. Travelers were responsible for removing and replacing the bars when they passed through. Other gaps or cartways were closed off with gates. There was also a road through the fence that led to West Deerfield and Conway.

Fencing still separates a few of Historic Deerfield’s Museum houses from the Street, but most fencing around the Meadows and homelots disappeared as livestock numbers decreased. Today, wire fencing controls herds of dairy cows on some lots, but the Common Field Fence only survives in the form of archaeological soils stains.