In 1876, the Centennial World’s Fair in Philadelphia equally commemorated our country’s past and envisioned its bright future. This fused energy swept into Deerfield with the arrival of artist James Wells (“Champ”) Champney and his writer wife Elizabeth Williams (“Lizzie”) Champney that summer. It was a homecoming of sorts for Elizabeth as a descendant of the distinguished Williams family whose roots stretched back two centuries to the town’s founding. They settled in her ancestral home on The Street, with Lizzie inheriting it after her parents’ deaths in the mid-1880s. The Champneys, a couple frequently on the move, spent several years and summered for many more in this house while alternating between their New York City residence and trips abroad. Even when away from Deerfield, they remained enmeshed in the life and history of the town that served as a wellspring of inspiration for both the artist and the writer.

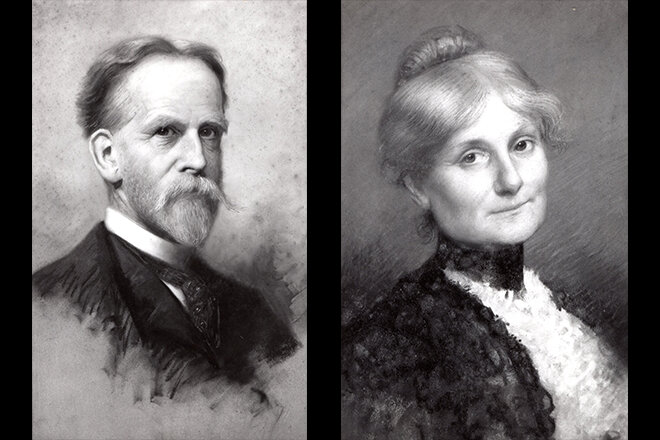

Photos of pastels of James Wells Champney and Elizabeth Williams Champney done by him. Champney Papers, Historic Deerfield Library.

Photograph of Elmstead and studio taken by the Allen Sisters after 1885. Champney Papers, Historic Deerfield Library.

Champ and Lizzie first met in the mid-1860s when he was her drawing instructor at a female seminary; he later furthered his artistic education in Europe and she studied at Vassar College. Their paths crossed again in 1873 in Kansas when Champ, a well-established artist at this time, toured the region working on illustrations for the Scribner’s Monthly series “The Great South.” Lizzie, living with her family and unhappily engaged to a farmer, jumped at the chance to elope with Champ, confessing to her brother that he was her first love in a letter breaking the rather shocking news.[1] The newlyweds soon sailed for Paris where their son was born the following year, with a daughter completing the family two years later in Deerfield.

Champ quickly built a studio on the Deerfield property after arriving to capture genre scenes of local village life and picturesque landscapes in oil, pastel, and pen and ink. The studio doubled as a space for his artistic creations and an entertaining space: “a delightful resort for his artist and literary friends. Here are hundreds of sketches of projected pictures, figures studies, or reminiscences of travels abroad…”[2] He was soon appointed Professor of Fine Arts at nearby Smith College and taught summer art classes en plein air. Despite a perpetually busy schedule, he threw himself into community life by lecturing on a variety of subjects to benefit the village library, the Town Pump Fund, and other charities. He illustrated his lectures, or “chalk talks,” with blackboard drawings, sketching them with “astonishing rapidity…a source of wonder and admiration alike”[3] for the audience. He became a lifetime member of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association (PVMA), the local historical society, in 1879 and served several times on its Council.

Painting of woman and child, probably Elizabeth Williams Champney and daughter, in the south yard of the Champney House in Deerfield, by James Wells Champney, 1879. HD 63.352.

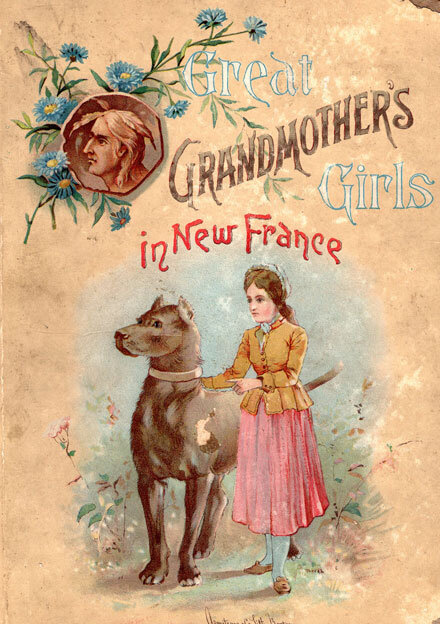

Lizzie’s achievements have unfortunately been overshadowed by her husband, yet she was no slouch once her career took off, racking up an impressive number of articles for such popular magazines as Scribner’s, Century Magazine, Harper’s, and St. Nicholas and over 50 books, all while raising two children and managing a household. She had always dreamed of becoming a writer; perhaps her literary Williams ancestors endured in her DNA although her works were travel writings, juvenile literature, and fiction rather than sermons and theological tomes. The couple collaborated on many works, he with providing illustrations for her articles and books, including the young adult series “Three Vassar Girls” that debuted in 1883. The first book proved so popular that ten more followed, each highlighting a new country or region in Europe and North and South America that the Champneys had visited. This series solidified her reputation with Lizzie herself noting, “her husband’s work provided bread and butter for the maintenance of the family, but the Vassar Girls series provided the jam.”[4] Along with her husband, she embraced her community and her heritage with involvement in the PVMA, writing essays and poems based on local historical events for its annual meetings and in books such as “Great-Grandmother’s Girls in New France,” a novel based on her ancestor Eunice Williams’ capture by Native Americans in 1704.

Elizabeth Williams Champney, Great-Grandmother’s Girls in New France: The History of Little Eunice Williams (Boston: Estes & Lauriat, 1887). Historic Deerfield Library.

Their idyllic life came to an abrupt end in 1903 with Champ’s death in an elevator accident at New York City’s Camera Club. Lizzie then mostly rented the house until selling it in 1913; she later moved to the west coast to live with her son and died in 1922. A memorial service was held in Deerfield for the Champney family in 1930, a year after their son passed, the daughter having predeceased both of them in 1906. All four Champneys are buried in Deerfield, a testament to the place that they loved and cherished.

Ed. Note: Historic Deerfield purchased the Champney home in November 2018 for the future use of the museum’s Summer Fellowship Program. The house is currently undergoing renovations, and Historic Deerfield’s Director of Historic Preservation, Eric Gradoia, has been exploring the house in a series of YouTube videos.

Learn more about the Champneys in this talk with Historic Deerfield Librarian Jeanne Solensky.