In an essay titled “On the Education of Youth in America,” lexicographer and textbook author Noah Webster (1758-1843) declared that every child should learn about the settlement and geography of the United States in order “to call home the minds of youth and fix them upon the interests of their own country… as well as enlarging their understanding.” Publishers heeded this advice during the period of the New Republic by issuing numerous atlases and geographies to meet the demands of an emerging American market.

One of the subscribers to Webster’s Collection of Essays was Jedidiah Morse (1761-1826), historian, clergyman, and principal founder of the Massachusetts Historical Society. While still a divinity student at Yale, Morse published the first American geography primer, Geography Made Easy (New Haven, 1784). The second edition (Boston, 1791) included the dedication: “To the Young Masters and Misses throughout the United States, the Following Easy Introduction to the Useful and Entertaining Science of Geography, Compiled particularly for their…early Improvement.” As Webster advocated, an emphasis on learning “the principles of virtue and of liberty, and an inviolable attachment to their own country,” had begun to take hold.

Some of the instruction in these principles occurred in academies which spread throughout New England and other parts of the new nation. Along with subjects such as grammar, mathematics, and languages, students could attend classes on geography and map drawing, the latter being thought particularly appropriate for female education. Deerfield Academy offered such classes taught by the highly talented Orra White (1796-1868) who worked with Edward Hitchcock during his tenure as the Academy’s Preceptor or headmaster, prior to their marriage in 1821. Most academies taught geography through an understanding of maps, perhaps influenced by Emma Willard’s teachings. Willard (1787-1870) declared maps “the written language of geography,” and persuasively argued for their use in the classroom. This often took the form of students creating a graphic representation, whether with pen, ink, and watercolors, or needle and thread, or some combination of the two. The demanding exercise of map copying could result in an object valued and saved by generations of the student’s family. While individual maps are something of a rarity, an entire atlas is an exceptional accomplishment.

Historic Deerfield has several examples of these cartographic treasures. Most recently acquired, through the generosity of the Deerfield Collectors Guild, is “A Book of Maps Executed by Emily Draper. Greenfield Mass 1822” (HD 2020.6). The daughter of Nathan and Hannah Whiting Draper, Emily (1803–1865) may have been a student, or more likely a teacher, when she created her remarkable atlas. Her older sisters, Eliza and Hannah, advertised their school for girls in Greenfield in the Franklin Herald of April 21, 1818, offering instruction in “most of the useful and ornamental branches of Education.” By 1822, nineteen-year-old Emily could have been assisting with the school; her future work as Preceptress of Deerfield Academy, and teacher at Miss Draper’s Seminary for Young Ladies, founded in Hartford, CT, by her sister, Julia, attest to her abilities as an educator. With no other documentation to draw on, we can only speculate on the exact circumstances of the atlas’s creation.

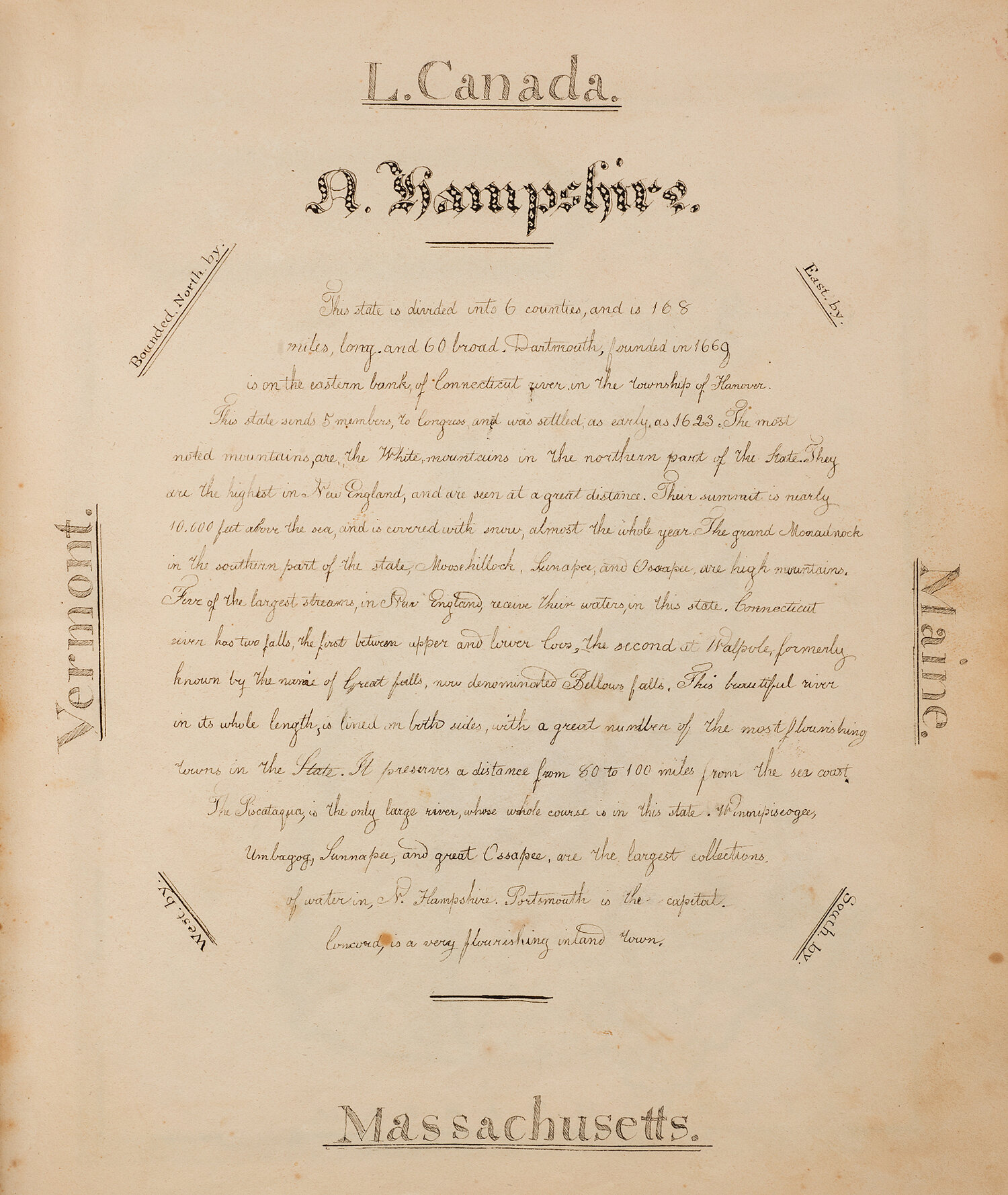

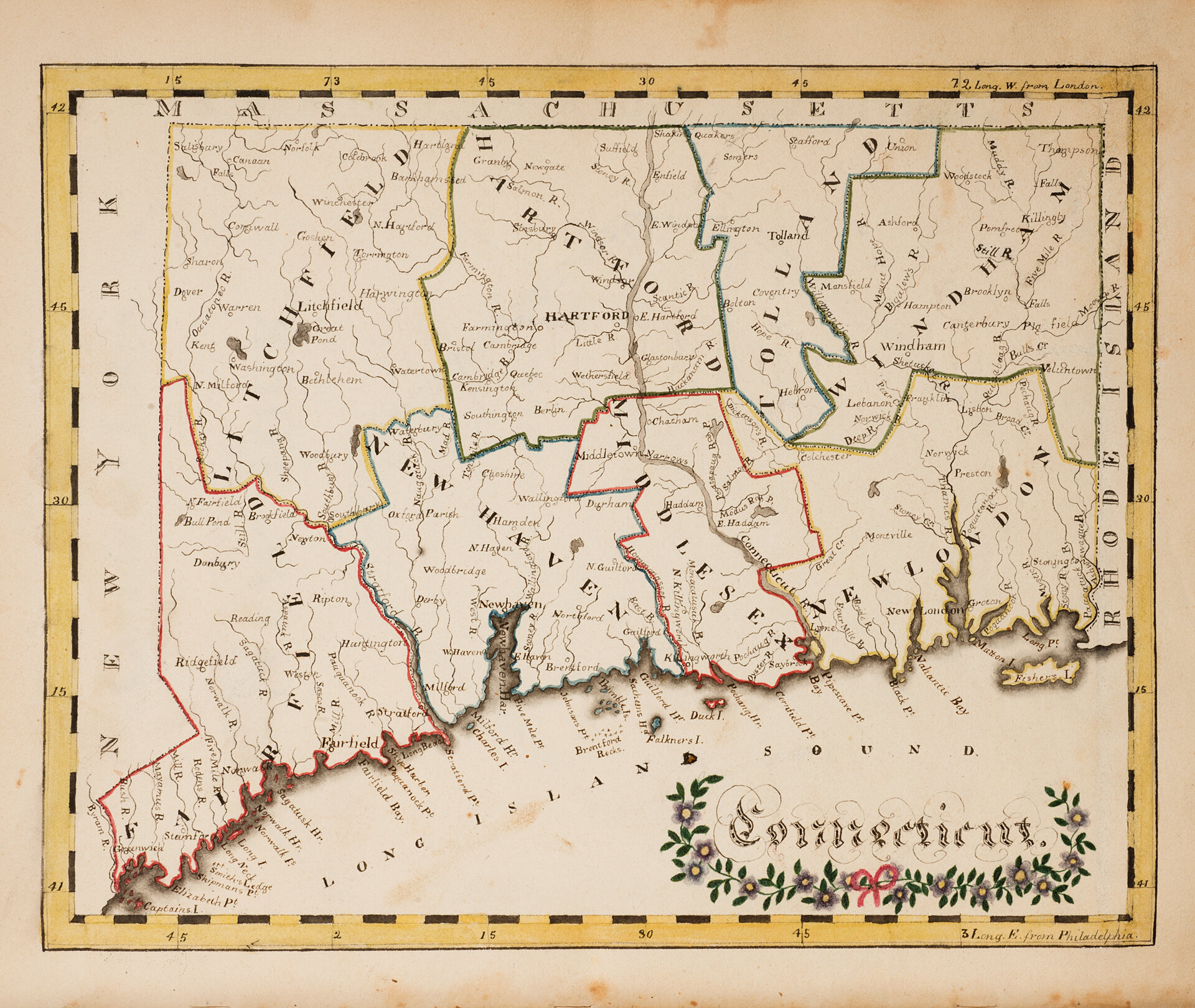

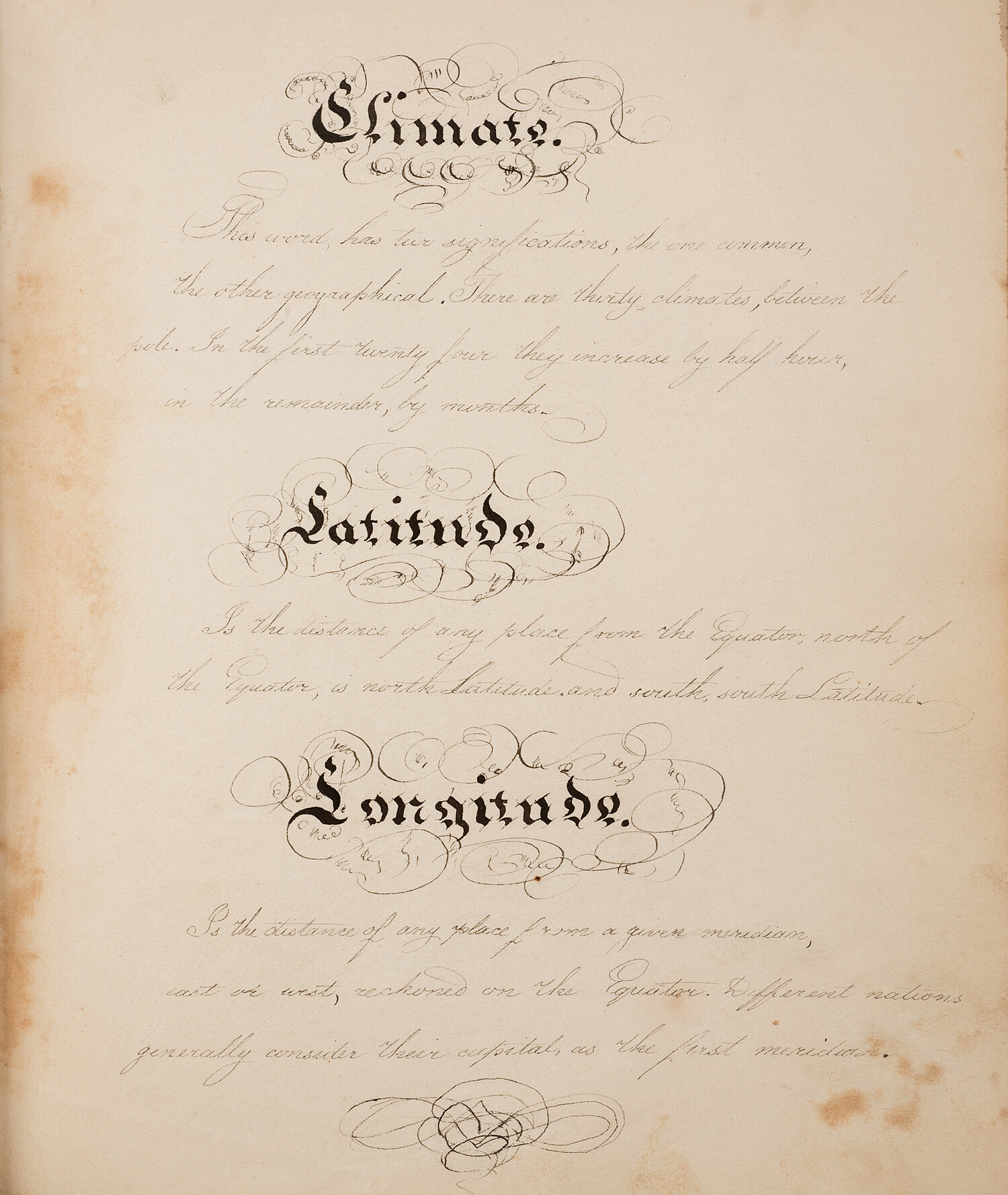

Emily Draper’s bound volume measures 8.75 x 7 inches, and consists of 56 leaves, including a calligraphic title page, 32 pages of calligraphic text and diagrams, and 19 full-page maps done in pen and ink. Many of the maps are hand colored in outline, a technique referred to as illumination. Most of her maps feature finely rendered figural or ornamental title cartouches, mostly floral and seemingly of her own design. The motifs of intertwined vines and flowers are suggestive of needlework patterns and other varieties of visual culture seen in calligraphy, furniture ornamentation, pattern books, etc. The finely rendered schematic representations of individual states with their physical descriptors are examples of artistic penmanship in the service of geographical knowledge.

Draper’s maps depict the United States, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee. In the border above and below most maps she noted degrees of longitude, measured from London or Philadelphia. American mapmakers of the early 19th century typically substituted Washington for London as the prime meridian; Draper’s map of the United States offers no longitudinal references. The young cartographer would have relied on a printed atlas of American states to guide her, several of which had been published by 1822. Clues to her source may appear in geographical variations or absences, such as Franklin (formed 1811) or Hampden (formed 1812) counties missing from her map of Massachusetts. The state diagrams or words maps indicate that she also made use of a geography text. Whichever sources she worked from, Emily Draper created a stunning example of a book of maps with the addition of meticulous calligraphic pages and beautiful non-cartographic designs.