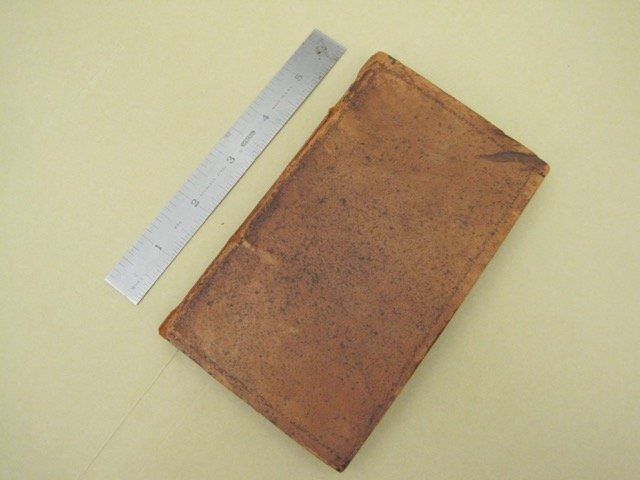

Over the past decade, scaleboard bindings have attracted the interest of the book history community. Named because the book covers were made of thin pieces of wood that had been shaved, planed or scaled down to just several millimeters in thickness, this binding style was popular almost exclusively in New England from the early 18th through the early 19th centuries.

Seven years ago, I wrote a post for this blog on an initial survey I conducted of scaleboard bindings in the Historic Deerfield Library collection [1]. It included details of eight different scaleboard bindings—a number which, with further investigation, has since doubled. The books were similar in all respects—place and date of publication, size, content and structure—to the several hundred documented scaleboard bindings in two previous large studies encompassing both public and private collections throughout the United States [2,3].

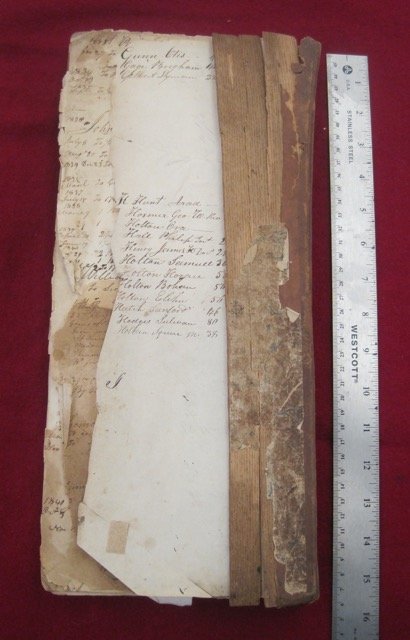

In early 2022, while I was evaluating the Library’s collection of account books prior to a repair and conservation project, librarian Heather Harrington brought to my attention a previously overlooked one from the Colton Family of Northfield, MA dating back to the 1830s. It had arrived at the library in 2008 as part of the Colton Family papers, including those of Richard Colton, keeper of the account book, who worked as a farmer as well as a wagon-maker, plowman and surveyor. He also served locally as a sheriff, coroner, justice-of-the-peace and state legislator.

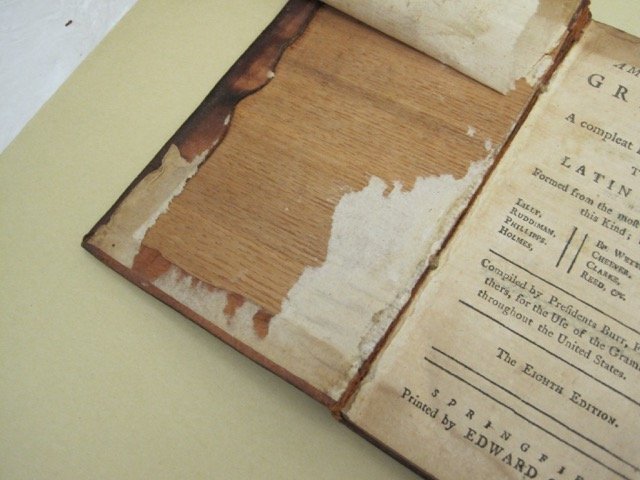

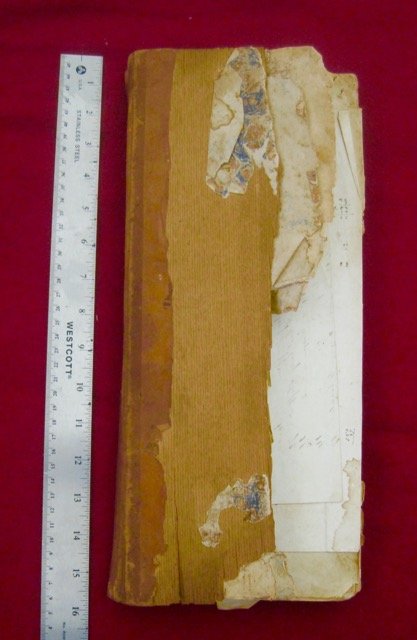

The book measured approximately 16” X 6” X 1”, was quarter-bound in calf leather, and several fragments of marbled paper were still attached on what remained of the covers (Fig 2). The grain of the wooden covers (likely quarter-sawn red oak as determined by Historic Deerfield’s former Director of Historic Preservation Eric Gradoia) ran vertically (head-to-tail in book jargon), unusual for scaleboard bindings in general. They measured only two to three millimeters in thickness. Because of the combination of size and grain direction, they had split lengthwise with barely half a board remaining as a front cover and less than a third on the back. The missing cover fragments did not accompany the book.

The book was the largest scaleboard binding I had ever seen, and a review of published scaleboard surveys along with an email from scaleboard expert Julia Miller at the University of Michigan confirmed that the book was probably the largest scaleboard binding documented to date. The previous ‘largest’ was an account book in the collection of the Library Company of Philadelphia that measured 9” tall. Coincidentally, when I contacted Miller, she was completing the revision of her original look at scaleboard bindings [4] from over a decade ago. She immediately composed and added this footnote to her updated manuscript based on the information I had provided:

Binder John Nove recently sent me a description and images of a scaleboard binding that served as a farm account book in Northfield, Massachusetts from 1833 to 1866 – a blankbook, or stationery binding, belonging to the Historic Deerfield Library in Deerfield, MA. The book is in agenda format (also called ready reckoner or narrow format) and measures 15 ¼ x 6 x 1 ½ inches. It is described as a quarter binding of calf with marbled paper sides over vertical-grain scaleboard, likely quarter-sawn red oak, sewn on three recessed cords. The wood has vertical cracks and has lost part of its lower board; the marbled paper is worn with large loss areas. Personal communication from John Nove, 10 February 2022.

Account books (or “ready reckoners” as Miller calls them) belong to a category of books called stationery bindings. Often made by specialized bookbinders—or imported from Europe—they were the equivalent of today’s blankbooks or journals: off-the-shelf items waiting to be filled with the purchasers’ data. In a review by Chela Metzger of such blankbooks in the collection of the Winterthur Library [5], she identified several much smaller scaleboard account books, two of which curiously had one scaleboard cover and one standard pasteboard cover. In an email, she said that she had never encountered a scaleboard blankbook as large as Colton’s, but added that among the largest she had ever seen were books for musical notation, but oriented in the ‘landscape’ rather than ‘portrait’ dimension.

Knowing that at least one scaleboard account book had been used locally, I have begun to search for others with the hope of identifying their original source of manufacture. To date, I have found nothing comparable in the collections of the American Antiquarian Society, the New England Historic Genealogical Society, the Boston Athenaeum or several local historical societies. Printed scaleboard bindings have been identified bearing the imprints of local publishers in Greenfield, MA, Worcester, MA, Springfield, MA, Brattleboro, VT, and Keene, NH. Might any of these publishers have also produced or distributed blank scaleboard account books?

References:

1. John Nove, “Scaleboard Bindings in the Henry N. Flynt Library,” The Village Broadside (blog), Historic Deerfield, Jan. 30, 2015.

2. Julia Miller, “Not Just Another Beautiful Book: A Typology of American Scaleboard Bindings,” Suave Mechanicals – Essays on the History of Bookbinding 1 (2013): 246-315.

3. Renee Wolcott, “Splintered: The History, Structure and Conservation of American Scaleboard Bindings,” The Book and Paper Group Annual 32 (2013): 56-79.

4. Julia Miller, Books Will Speak Plain – A Handbook for Identifying and Describing Historical Bindings (Ann Arbor, MI: The Legacy Press, 2010)

5. Consuela Metzger, “Colonial Blankbooks in the Winterthur Library,”

Suave Mechanicals – Essays on the History of Bookbinding 1 (2013):94 – 161.