This time of year brings a barrage of wonderful treats that I find hard to resist. Chief among them in this season of overindulgence is chocolate. By nibbling on a few pieces, I am doing “research” for an upcoming lecture as part of Historic Deerfield’s virtual program, “Winter Evening Entertainment: History of Chocolate in Early New England,” which starts on Wednesday, January 6, from 6:30 to 7:30 pm. The three-part program is designed for you to curl up with a cup of hot chocolate and learn something new.

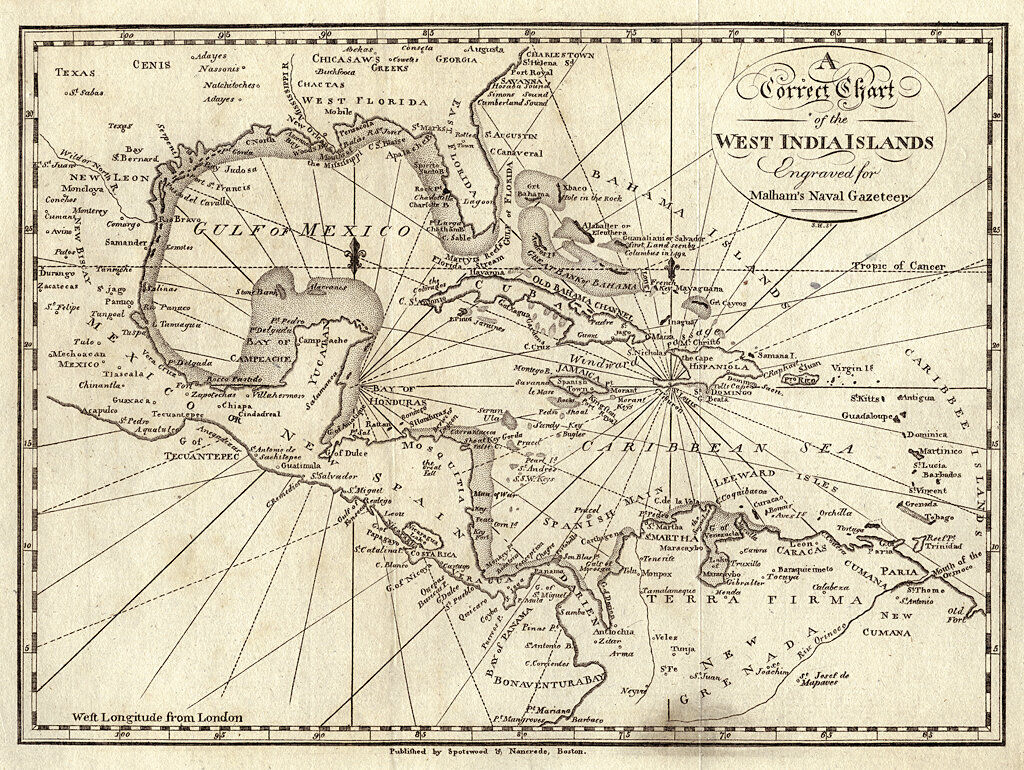

Although cacao trees don’t grow in our climate, chocolate has a long history in New England, given our close economic connections to the West Indies. New England merchants supplied barrel staves, lumber, onions, salt fish, salt beef, and horses to the Caribbean in exchange for sugar, molasses, rum, and cacao. Similar to sugar manufacturing, cacao plantations required a consistent demand for labor, which led to the forcible transportation and enslavement of West Africans to supply this commodity.

New England merchants dominated the trade in cacao from the Caribbean and South America. Some of the earliest references to chocolate appear in Boston. Silversmith and mint master John Hull’s diary for winter 1667-1668, recorded the loss of his ship Providence “cast away on the French shore [carrying] cocoa.”[1] By 1670, Dorothy Jones and Jane Barnard were each granted a license from the selectmen of Boston for keeping a house of “publique Entertainment” (a tavern) to sell “Coffee and Chucaletto.”[2]

Along with Philadelphia, New York, and Newport, Boston became a major importer of cacao and source of ground chocolate for New England and more distant colonies. Nearly 70% of British North America’s cacao came from sources other than the British West Indies,[3] much of it smuggled from Venezuela. Britain did not possess many thriving cacao plantations in the West Indies, even with its takeover of Jamaica in 1655. Unfortunately, a blight destroyed the trees in the 1660s, leading British West Indian plantation owners to focus on sugar, indigo, and tobacco. Boston newspaper advertisements often specified the source of cacao – frequently listing the export locations of Maracaibo and Caracas in Venezuela, Martinique and Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in the French West Indies, and Surinam and Cayenne, located in the Guianas of South America. Cacao, commonly called “cocoa nuts,” arrived in Boston by the hogshead, barrel, or bag. Chocolate makers or grinders utilized these large cacao shipments roasting and processing them for retail. Dry goods merchants also sold beans and prepared chocolate in smaller quantities.

Boston supported more than 24 chocolate grinders throughout the 18th century. Early in the century, grinders were primarily situated in the North End of Boston, later spreading out to other areas such as the South End, New Boston,[4] Charlestown, Watertown, and Dorchester. Grinders offered their own product for sale or provided roasting and milling services for others. Preparing cacao was a labor-intensive process. The chocolate mill’s free and enslaved laborers[5] roasted the cacao beans over charcoal, cracked and removed the outer shells, and then ground chocolate nibs either by hand or by water or horse power. When chocolate is ground, the cocoa butter is expressed giving it a consistency similar to honey. Once ground and flavored with sugar and spices, chocolate was placed in tin molds to firm up.

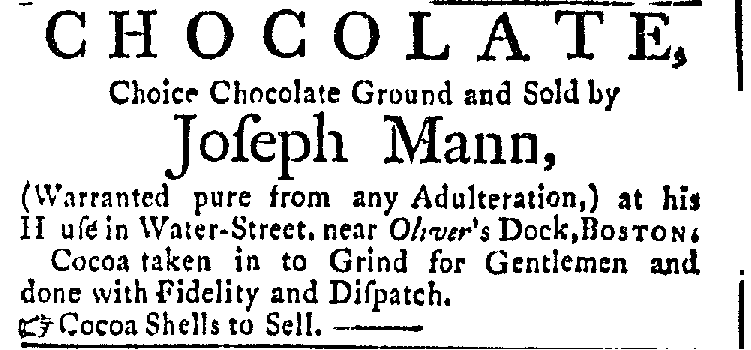

Unfortunately, not much is known about how cacao was processed in Boston; existing structures and equipment do not survive or have not been recognized as being specific to chocolate. Some sources of information include auction notices for chocolate mills. Listed equipment ranged from iron kettles, pans, pestles and nut crackers, muslins or sieves for cleaning the shells from the nuts, and millstones or chocolate stones and rollers. The later was a dished stone grinding surface with a pan of charcoal underneath. A stone roller similar to a rolling pin would grind the nibs until it achieved a smooth texture, although 18th-century chocolate was gritty when compared with today’s product. The smaller the particle size, the more chocolate flavor is released. Millstones made grinding chocolate easier. Chocolate makers often also sold ground mustard, flour, and at times, tobacco. Given the problem of adulterated foods, grinders often warranted their work marking their chocolate with their initials as a symbol of purity. Unscrupulous chocolate makers added cheaper fats, starches, and colorants such as brick dust to extend and tint products. The shells surrounding the cacao beans found buyers, using them to make a less fatty, steeped drink or “tea.”

Chocolate balls or lozenges, wrapped in paper, were sold individually; larger quantities were retailed in boxes. In the early 18th century, Bostonians frequently presented chocolate as a gift. Judge Samuel Sewall noted these chocolate offerings several times in his diary: “Monday, October 26, 1702 … Visited languishing Mr. Sam Whiting, I gave him 2 Balls of Chockalett and a pound of Figgs, which very kindly accepted”[6] and on “March 31 [1707] Visited Mr Gibbs, presented him with a pound of Chockalett and 3 of Cousin Moodey’s sermons.”[7] One wonders whether the sermons were appreciated as much as the chocolate?

Serving chocolate in Hall Tavern’s North Kitchen. Historic Deerfield. Photography by Penny Leveritt.

Before chocolate could be consumed, it needed preparation. The majority of chocolate sold made hot beverages, but some found its way into puddings, tortes, and creams. Using a knife or grater to scrape the chocolate, shavings would be dissolved in a chocolate pot or skillet with either hot water, milk or wine, and sweetened to taste. Recipe books and medical manuals promoted chocolate scented with musk or ambergris, highly spiced with cinnamon, mace, nutmeg, cloves, and peppers, or fortified and thickened with eggs or ground nuts. Before serving, the chocolate mixture needed to be frothed using a chocolate mill, a notched wooden stick, to whip up an essential foam. A chocolate cup, mug, or porringer served the beverage for a family’s breakfast, a nutritional supplement for the sick, or a portion of a soldier’s rations. The naturally high fat content (over 50% of chocolate is cocoa butter) of chocolate made it a nutritional boon to the 18th-century colonial American diet.

The proximity of cacao plantations to the American colonies kept prices accessible to a majority of the population including soldiers, the poor, and prisoners.[8] In 1756, dry goods merchant Elijah Williams of Deerfield, Massachusetts, purchased 40 pounds each of tea, coffee, and chocolate on a trip to Boston. While tea cost 37 shillings 6 pence per pound and coffee only 8 shillings per pound, chocolate was priced at 10 shillings per pound.[9] With the price of a day’s labor estimated at 2 to 4 shillings,[10] these stimulating beverages were still not commonly drunk every day.

History and chocolate are a great combination – but perhaps not as great as chocolate and peanut butter. I will let you decide. To learn more about the history of chocolate, the cacao tree, and chocolate use in colonial Deerfield – please join us for a “Winter Evening Entertainment: The History of Chocolate in Early New England.” More information is available on www.historic-deerfield.org or by clicking this link:

[1] S. Bercovitch, ed., The Diaries of John Hull, Mint Master and Treasurer of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay (Boston: J. Wilson and Son, 1857), reprinted in Puritan Personal Writings: Diaries (New York: AMS Press, Inc., 1982), 158.

[2] Gerald W. R. Ward, “The Silver Chocolate Pots of Colonial Boston,” in Falino and Ward, eds, New England Silver and Silversmithing, 1620-1815 (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2001), 61.

[3] James F. Gay, “Chocolate Production and Uses in 17th and 18th-Century North America,” in Grivetti and Shapiro, eds, Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley and Company, 2010), 285.

[4] New Boston is one of the few regions of the city that has had a history of ever-changing borders, but the 18th-century boundaries were probably in the general vicinity of west and north of Beacon Hill and west and south of Mill Pond. Annie Thwing, The Crooked and Narrow Streets of the Town of Boston (Boston: Marshall Jones Company, 1920), 58.

[5] Several advertisements in18th-century Boston newspapers advertise for the return of runaway, enslaved laborers to chocolate grinders.

[6] M. Thomas, The Diary of Samuel Sewell, Volume 1, 1674-1708, 476, quoted in Gay, Chocolate Production, 292.

[7] Thomas, The Diary of Samuel Sewell, Volume 1, 563-64, quoted in Gay, Chocolate Production, 293.

[8] Gay, Chocolate Production, 285.

[9] Account Book of Elijah Williams, Deerfield, Massachusetts, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library.

[10] “Wages of Early Building-Trade Workers,” Monthly Labor Review 30, no. 1 (January 1930): 9.