Wood has been used to craft the covers of books for nearly 1500 years. Its use peaked in the Medieval Period when massive tomes with massive ʻboardsʼ and sturdy hardware became commonplace in religious institutions and the homes of the wealthy. With the subsequent development in Europe of the printing press and the parallel development of paper-making, in came more modestly sized books along with their lighter-weight pasteboard and pulpboard covers. In the 17th and 18th centuries, though, a tradition remained of constructing books using very thin pieces of wood – often only a couple of millimeters thick – called scaleboards or scabbards. It was this tradition that was carried to America by craftsmen and flourished primarily due to financial considerations: it was more economical to rely on local wood for cover material than to import paper-based cover stock.

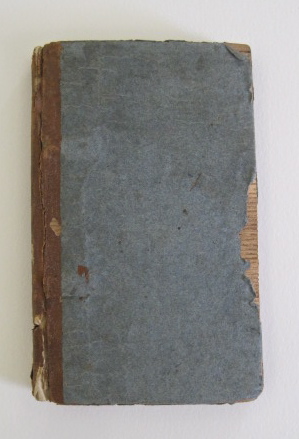

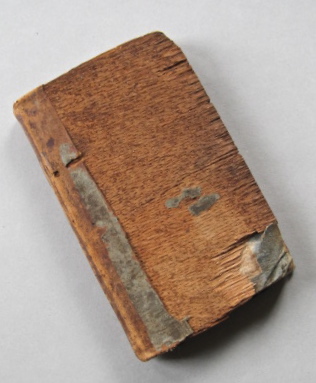

The books produced throughout the Colonies with these scaleboard bindings usually contained sermons, orations, survival stories, music or educational material. The grain of the wood ran horizontally, vertically or rarely, one cover with each orientation. The thin wooden boards were covered with leather, plain paper or a combination of the two. Typical examples are shown in Figures 1 & 2.

Young Scholarʼs Guide, a typical 18th century scaleboard binding with a leather (sheepskin?) spine and blue-gray paper cover. Had the paper not worn away to reveal the wood underneath, the bookʼs identity as a scaleboard binding would not have been so obvious.

The well-worn front cover of Captivity of Maria Martin shows the grain and roughness of a typical scaleboard. The wood from which the covers of this book were made has tentatively been identified as ash.

These books have come under scrutiny lately as the result of a survey undertaken and published by Julia Miller. She examined 858 scaleboard bindings at the American Antiquarian Society, Harvard University, the University of Michigan, and the Library Company of Philadelphia as well as in two private collections. Bibliographic information was recorded as well as information related to the physical attributes of each of the books – including grain direction and thickness of the wood, binding style and how the boards were covered. All this information was then assembled into the first comprehensive study of this style of binding.

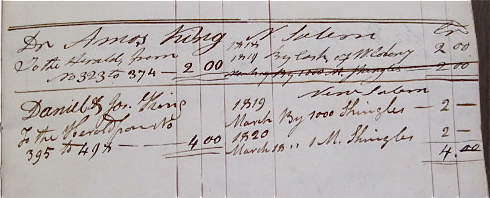

In tracing the ʻlife-historiesʼ of some of the books, she discovered that unlike today, printing, binding, publishing and marketing were often undertaken by the same individual. One such well-documented multitasking individual was Isaiah Thomas of Worcester. In addition, her examination of his account book dated 1794-1814 revealed two entries for “bundles of scaleboards”. Similar but more recurrent entries were recently found in an account book in the Flynt Library belonging to Ansel Phelps, a Greenfield printer, in which payment/barter with “shingles” is mentioned. Although scaleboards for books and shingles for roofs were crafted similarly, it is not entirely clear to which Phelps is referring.

The discovery of a book in the collection of the Flynt Library with a worn paper cover revealing the wooden scaleboard beneath led to a search of the stacks for other examples. Nine have been documented to date and are summarized in the table below.

Nine Scaleboard Bindings in the Flynt Library Collection

(listed as title/author // publisher/publication date // dimensions /cover material; the wood grain in all nine books runs horizontally; board thickness ranges from 1.5 – 3.3mm)

Day of Doom – M. Wigglesworth John Allen, Boston, MA (1715)

135 x 85 x 7mm; full leather w. blind tooling

American Latin Grammar – (compiled by committee) Edward Gray, Springfield, MA (1793)

155 x 93 x 15mm; paper w. leather spine

Northampton Collection of Sacred Harmony – E. Mann Daniel Wright & Co., Northampton, MA (1797)

135 x 222 x 15mm; paper w. leather spine

American Compiler of Sacred Harmony – S. Jenks & E. Griswold pub. unk., Northampton, MA (1803)

130 x 222 x 12mm; paper w. leather spine

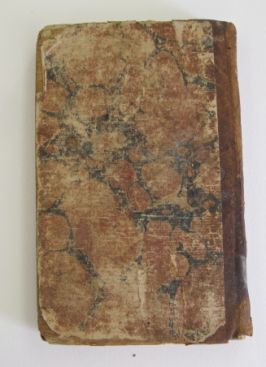

A Serious Address on Coughs and Common Colds – T. Hayes

W. Fessenden & G.W. Nichols, Walpole, NH (1808) 172 x 110 x 12mm; marbled paper w. leather spine

Columbian Reader – R. Dickinson

R.P. & C. Williams, Boston, MA (1818)

170 x 105 x 12mm; paper w. leather spine

Captivity of Maria Martin – M. Martin

F. Merriam & Co., Brookfield, MA (1818) 142 x 88 x 10mm; paper w. leather spine

Young Scholar’s Manual – T. Strong Ansel Phelps, Greenfield MA (1824)

133 x 85 x 10mm; paper w. leather spine

Improved Reader – A. Grove

Phelps & Ingersol,Greenfield, MA (1839) 147 x 93 x 15mm; paper w. leather spine

In terms of physical characteristics, none of these books is significantly different from Millerʼs published study group: similar content, similar cover material, similar board thickness and size. What is of note, however, is that only two of these nine titles (Day of Doom and American Latin Grammar) were recorded by her. Information on these books will be entered into data sheets provided by Miller and submitted. Meanwhile the search will continue for other scaleboard bindings in the Flynt Library collection.

Two decorated covers – marbled paper on Common Coughs and Colds (left) and a blind tooled border on American Latin Grammar

John Nove, a bookbinder in Deerfield, MA, has been repairing, binding and constructing protective boxes for the Flynt Library collection for the past four years. He wishes to acknowledge the assistance of David Bosse and Heather Harrington at the Library for bringing their scaleboard bindings to his attention and for encouraging him to write this blog entry. Millerʼs study was published as a chapter in Suave Mechanical, vol. 1 (2013), a book she edited.