Epaphras Hoyt (1765-1850) was a curious man. He was a surveyor by trade, a military historian by choice, and a student of the natural world by interest. In the late 1830s, he had largely retired from surveying and began spending more of his time in his hometown of Deerfield. He began writing journals of his daily experiences that he would keep for the rest of his life. (These journals are part of the collection of the library at Historic Deerfield.) In these journals he often discussed various scientific mysteries that fascinated him. In 1838, and again in 1840, Hoyt became interested in sap.

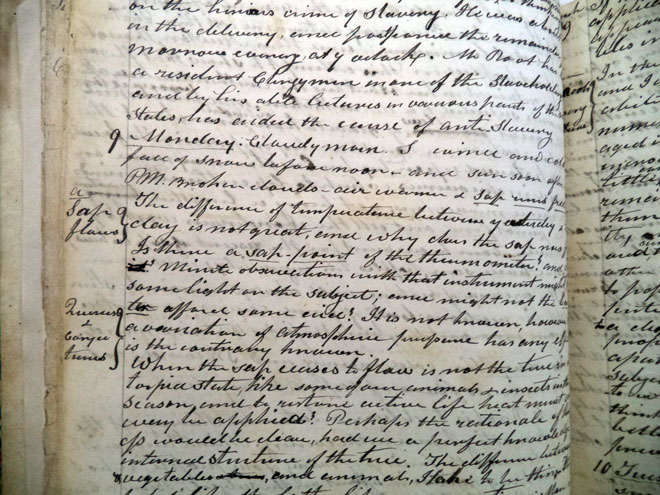

“Why does sap flow?” was written in Hoyt’s journal many times. This question puzzled him to no end. Like any good scientist, Hoyt began investigating. He observed many things about the flow of sap. He noted that cold nights and warm days were necessary; that the sap season varied each year; that late season sap was often more bitter tasting; and most puzzling of all, that gallons could be produced daily per tree! Hoyt also talked with many of the “sugar men” about what they knew of the process. He and Dr. Stephen West Williams (1790-1855) conducted experiments with sap to determine evaporation rates.

Hoyt, being an educated man who loved to read, also consulted books. He read about two proposed theories about why sap flows. The first theory, which he said was widely accepted, and published by the Royal Society, concluded that sap flows upward because of the same mysterious and unknown power that makes vegetables rise from the ground.

The second theory, which Hoyt read about in 1840, claimed that sap flows upward because the trees are filled with excess air, which when heat is applied, causes the sap to rise. Hoyt doubted this idea, and began to form his own theory.

Hoyt had previously determined that heat was essential to the process, needing warmer days to rise. At one point, Hoyt becomes a little obsessed with temperature and wonders if there is a “sap-point on the thermometer?” He also wondered if using a barometer to measure pressure would help with sap research. He later concludes that there is no evidence that a change in barometric pressure has any impact on sap flow.

Hoyt proposes that like some animals and insects who hibernate for the winter and need a dose of heat to return to their “active state” in the early spring, trees are hibernating in the winter, and the sap flow is a result of the sun and rising temperatures heating the tree and waking it up.

Of course all of Hoyt’s research ends with the lament that more research is needed on the internal structure and anatomy of the tree. Eventually, in late March of 1840, he seems to concede that no one knows the cause of the rise of sap, and that someday someone will discover the answer. They will be the “next Harvey,” referring to William Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of the blood in the 17th century. With that, his fascination with sap ends.

It is not until 1894, when the cohesion-tension theory was put forth, that the flow of sap was satisfactory explained. Much later than Hoyt scientists began studying the internal structures of the tree, leading to a better understanding of a tree’s anatomy and rise and flow of sap and other materials through plants.

Unknowingly, Epaphras Hoyt came close to determining the reasons for sap flow. He correctly guessed that more knowledge of the internal structure of trees was needed. Like other amateur scientists, he studied a problem, gathered information and observations, and attempted to explain the natural world around him. Today men and women like Hoyt continue to observe the world around them and ask “why?” This continued curiosity is what propels us forward in technology, science, and exploration. Epaphras Hoyt was just one in a long line of people who have propelled us into the future.