Have you experienced the gut-punch when learning something surprising about a good friend? This is sometimes how it feels to study history. We learn the stories and voices of people from the past. Their world becomes less foreign but nevertheless remains impossible to reach. Every so often we find something unexpected.

“James Wells Champney died in 1903. Fell down an elevator shaft.” This was not a sentence I expected to read in my coworker’s notes about the genial painter.

James Wells Champney (1843-1903) was an artist best known for his portraits and genre paintings, and in particular his use of pastel. He also illustrated many of the books that his wife, Elizabeth Williams Champney (1850-1922), wrote. They traveled extensively throughout Europe, spending much time in Paris, where their son was born. Champney set up a prominent studio and home in New York but also settled in Deerfield, Massachusetts, making him something of a local celebrity.

On May 1, 1903, Champney found himself stuck in a stalled elevator between the fourth and fifth floors of an office building at 5 West Thirty-first Street in New York City. He was on his way to the New York Camera Club’s dark room on the ninth floor of the building. There was a delay because of a table that was being transported on the elevator at the time. Champney grew impatient and decided to lower himself physically to the fourth floor and continue on his way. However, he didn’t have the necessary momentum and ended up losing his grip on the floor of the elevator cage without being properly angled towards the next landing. The others who were in the elevator with him attempted to pull him back up, but they were ultimately unsuccessful. He fell sixty feet within the elevator shaft and died instantly. The “elevator boy” who was working there at the time was arrested in connection with the incident. Champney’s demise seems incongruous and abrupt when studying his otherwise idyllic life and work.

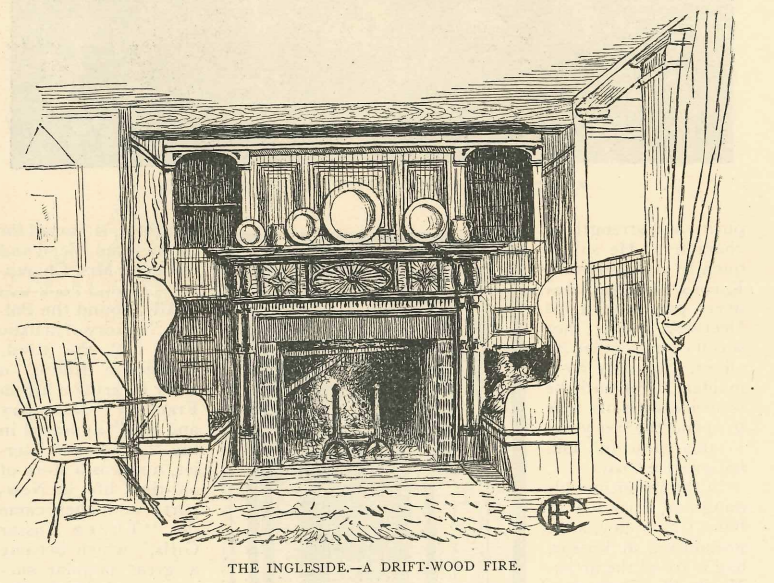

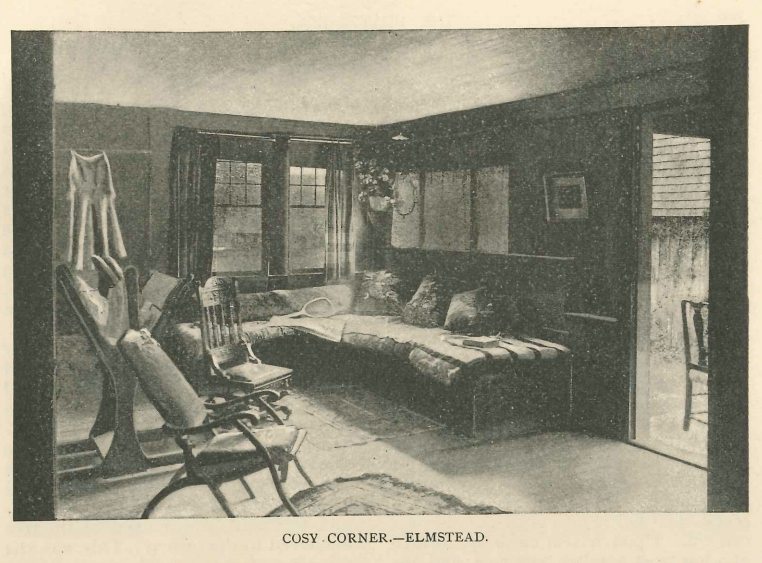

The Champneys were part of the Colonial Revival movement in Deerfield. While their primary residence was in New York, the changes they made to their home in Deerfield reflected their desire to retreat to the country and enjoy producing their art with other local artists. They turned what had been a tradesman’s home and shop into a place to read, discuss, and paint. They moved the building back under the shade of an elm tree (after an even larger shade-giving elm had fallen down in 1885) and named the property “Elmstead,” evoking an artistic day in the country. They also added a portico to the front and made several changes to the building’s structure, such as adding an inglenook, and moving the stairway from the center hallway.

Jenny June, “Typical Homes: Old Deerfield and Its Memories – The Home of the Champneys,” The Homemaker VI (September 1891): 456.

Elizabeth Champney inherited the property at 43A Old Main Street from her father Samuel Barnard Williams (1803-1884). Then in 1913, following her husband’s untimely death in 1903, Elizabeth sold the house to W. Scott Keith. It was in the possession of the Keith family until it was sold to Scott and Joanna Creelman in 1984. Historic Deerfield purchased the house in 2018.

At that point, the museum undertook an extensive updating process to turn the private residence into a multifunctional space to suit the needs of the organization. The museum worked with Jones-Whitsett Architects in Greenfield, MA, to accommodate modern safety concerns, while maintaining the existing footprint of the building and many of the interior details from the Champneys’ residence.

The first floor of the house is now completely ADA accessible, including a landscaped ramp and parking area outside. Space from the garage has been adapted into an ADA bed and bath suite on the first floor, to supplement the seven additional bedrooms on the second floor. A second stairway was added. New building systems were added, including heating and cooling, electrical, and fire detection and suppression systems. There is also high-speed data and internet, which will allow the museum to use the Creelman House to host webinars and meetings.

The museum will use the house primarily for temporary housing for guest lecturers, trustees, and conservators, and most significantly, the Summer Fellowship Program. This year, for the first time in many years, the fellows and their tutor will have the advantage of being able to spend the summer together in one house. The program is designed to show college seniors or juniors what it is like to work in a museum, teach them to analyze, interpret, and ask questions of material culture, and conduct archival research.

As we get ready to welcome the 2022 cohort of Summer Fellows to Historic Deerfield, let us be reminded that while history can be surprising, those who remain can adapt to changing needs and conditions. It takes careful looking to peel back the layers of history. The renovation of the Creelman House, undertaken with a sensitivity to the 18th-century character of the building as well as the Champneys’ vision, has helped to usher in a new era of use of the historic house under Historic Deerfield’s stewardship.

Jenny June, “Typical Homes: Old Deerfield and Its Memories – The Home of the Champneys,” The Homemaker VI (September 1891): 457.