By Heather Harrington, Associate Librarian

Every December in Deerfield visitors ask, “How did the early inhabitants celebrate Christmas?” The answer is always, “They didn’t.” When Puritans first settled in what would become Massachusetts, Christmas was just another day, not a holiday. As Congregationalism remained the dominant Protestant denomination in the area, Christmas-as-a-holiday continued to be a rare occurrence. It was only in the nineteenth century that Christmas celebrations began to occur more regularly.

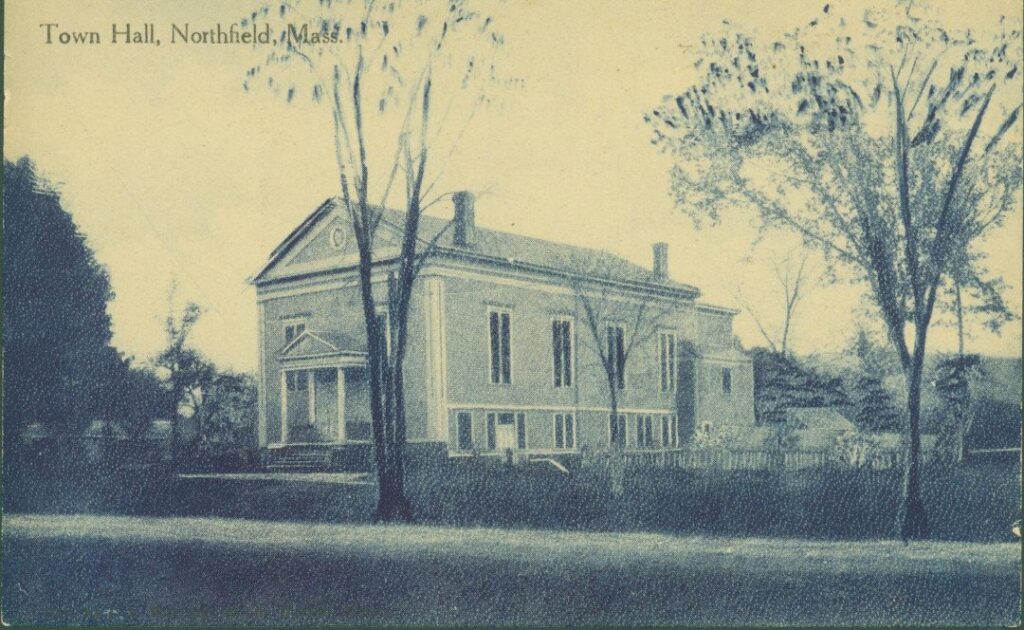

In December 1860, the town of Northfield held a Christmas festival at the town hall. Edward Colton (“Wells”) attended the event and wrote about it to his fiancée Susan Heard in Boston. He described the experience thus:

“Evening went to Christmas festival at the Town Hall.—The Hall was beautifully trimmed with Evergreen with a Christmas tree in the centre, near the entrance. Over the platform and near the ceiling was a Star and under this star was this motto beautifully arranged “Joy to the world, the Savior has come. Let all the earth rejoice.” These letters were made with evergreen and everything was in keeping. The Christmas tree was loaded with gifts And all the children under 12 years of age got a gift from the basket of Santa Claus—The Gifts from the tree were for the older ones mostly. It was from that I received my Gift-A Gift from Mr. Murray. A Book of Sacred Poems “Lyra Germanica”—This gift I believe was the first I ever received for a Christmas Gift.—There was a large gathering and all secured to enjoy it. At frequent intervals we had music both instrumental & vocal.—Thus have I told you of only a part of what was, that Eve.”

This description sounds like many Christmas parties we know today, but just looking at the date of the party (1860) shows how early what we might consider to be more modern notions (tree, Santa Claus, gift-giving) came to the Connecticut River Valley.

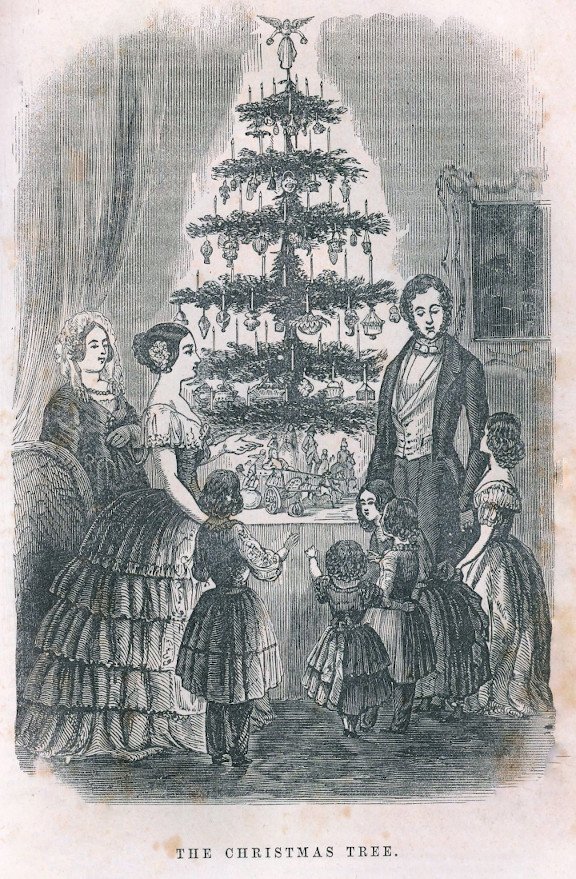

One of the things most surprising about this description of events is that Wells did not feel the need to explain to Susan who Santa Claus was, or the purpose of Christmas trees. He assumed she knew. From other letters in Historic Deerfield’s collection, we know that Wells was definitely the type of person to explain things to Susan if he thought for a second that she would not know what he was talking about. Indeed, Christmas trees were widely known by the 1830s, with the first known reference to an American Christmas tree in a Cambridge, Massachusetts family in 1835.[2] Christmas trees became more widely popular after 1850 when Godey’s Lady’s Book published a sketch of Queen Victoria and her family celebrating around a decorated tree. The magazine removed her crown and any other royal markers to make the image more “American.”[3] The image had its effect, making Christmas trees an expected part of the holiday.

What Wells does not do is describe in any detail what “Santa Claus” looks like. The only clue is that Santa had a “basket” of presents. Our modern view of Santa as a jolly, rotund man with white hair and a long beard, wearing red and white and carrying a sack full of presents was popularized in the late 1860s with the publication of Thomas Nast’s drawings. Before this time, Santa had many different looks as he slowly changed from a Dutch legend to a Christmas staple. In 1860 when Wells attended this Christmas party, Santa may have looked very different from what we picture today. Perhaps Wells’s Santa was thinner, did not have a beard, and was not dressed in red!

At the end of his description, Wells mentioned that he received a book from Mr. Murray (the minister) that was his first-ever Christmas present. This statement is not surprising, as Wells had grown up in Unitarian/Congregationalist family. Many Congregationalists preferred gift giving on New Year’s Day instead of Christmas. In addition, gift giving was often seen as reserved for children, especially in the first half of the nineteenth century. Perhaps as a child, Wells did not receive presents at Christmas. Whatever the reason, he waited a long time (twenty-nine years) for his first Christmas present.

Wells’s brief description of a Christmas party in 1860 could easily have taken place in this century. It certainly shows that modern ideas of Christmas celebrations had been firmly entrenched in the Valley by 1860.