Created by Historic Deerfield Director of Interpretation James Golden

Welcome to Week 13 of Maker Mondays. Check your social media feed or look for an email from us every Monday for a fun activity that you can do at home, inspired by history and the Historic Deerfield collections, using common household items.

Download a printable version of this activity (PDF).

This Monday we’re encouraging you to create your own commemorative plate. Throughout European and American history, people have used plates and other ceramics to display political and cultural ideals. Endowing food service items with powerful images makes the ideas they convey all the more intimate: we’re encountering those meanings every time we eat! Purchasing such wares let a consumer declare their ideals with their pocketbook, and then serving food on them demonstrated those beliefs to visitors and family.

First, we’ll show you some examples from Historic Deerfield’s collection, and then guide you in making your own commemorative plate.

HD 55.149

This beautiful plate from 1748 was made in the Netherlands of tin-glazed earthenware and is decorated with cobalt blue, iron red, and antimony yellow. At first, it might seem to be a simple domestic scene of a woman and a child in a cradle. However, it is deeply political. The colors and inscription tell a story about that child. The colors are those of the Dutch royal family, the House of Orange, and the initials and date reveal that the child is the future monarch (or “stadholder”) William V (1748-1806). This plate, then, celebrates the birth of an heir and affirms the owner’s commitment to the Dutch ruling family at a time when it was not popular with the whole of the country. It shows the owner to be an “Orangist” proponent.

HD 57.111

This punch bowl tells a wonderful comparative story. It was made in England about 1760 from white salt-glazed stoneware with overglaze polychrome enamels. It also shows its owner’s support for a monarch—but not the ruling one. This punchbowl depicts Charles Edward Stuart (1720-1788), known as the “Young Pretender” or “Bonnie Prince Charlie.” He was the grandson of James II (1633-1701), the King of England, Scotland, and Ireland who was deposed and dethroned in 1688 in favor of his daughter Mary II (1662-1694) and her husband William III (1650-1702). James II’s son James (1688-1766) and grandson Charles (pictured on the bowl) invaded the United Kingdom in 1715 and 1745, respectively, trying to win back the crown. Significant portions of the British population still supported them—especially Catholics, who were excluded from power at this time. Supporters of James II’s descendants—called “Jacobites”— would defy authority and drink toasts to the man they thought ought to be king and did so from this rebellious punchbowl. Putting the Young Pretender’s face on the vessel and celebrating him instead of the actual monarch was rebellious enough: to make it all the more evident, he is depicted in the clothing of the Scottish Highlands, the region that supplied soldiers to his campaign.

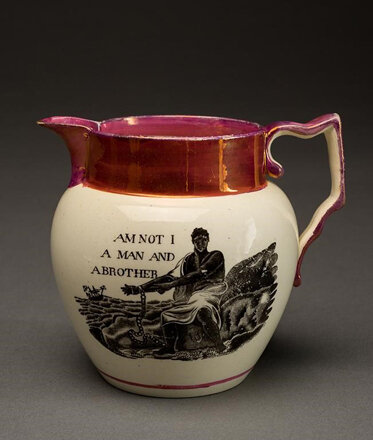

But commemorative ceramics aren’t all about kings and queens. Historic Deerfield is proud to have very recently purchased this jug:

HD 2019.45

This was made in England between 1820 and 1840 of lead-glazed, refined white earthenware, pink lusterware, and overglaze black enamel. The image is transfer-printed. This piece declares opposition to slavery by juxtaposing the image of an African man in chains and the quotation from an anti-slavery poem that reads “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” It may have been acquired at a fair where abolitionists—people who wanted the immediate end to slavery in the United States—could meet each other, hear speeches, and support the movement by purchasing goods like this. Abolitionism was a fringe, minority opinion in the United States at this time. Serving visitors in one’s home from a jug like this was a bold statement in favor of equality. It demonstrates to us now that opinions once thought to be radical and extreme can become accepted and acknowledged over time.

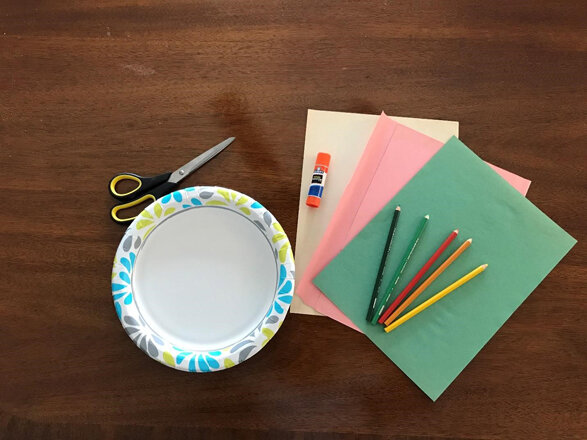

Now it’s time to make your own plate. You’ll need a paper plate, construction paper, scissors, glue, and colored pencils or markers.

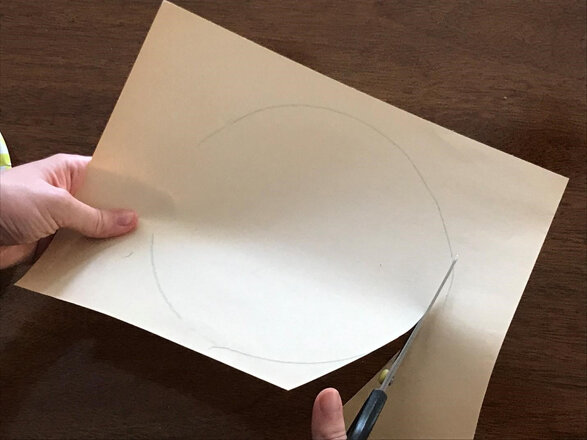

Step 1. Place your paper plate on a piece of construction paper. Use a pencil to trace a circle the size of the inner part of the plate. This will be the area you decorate.

Step 2. Cut out your circle and glue onto the inner part of your plate.

Step 3. Choose a person from your life, history, or the news whom you want to celebrate or commemorate. Draw a picture of them using pencils, colored pencils, or markers. Alternatively, you can print out a picture that you found on the internet.

Step 4. Think of things you associate with that person. For instance, if you chose your sister and she likes tiger lilies, you might draw some tiger lilies around the border of your plate. This is also an opportunity for political symbolism—are there images you associate with causes or people?

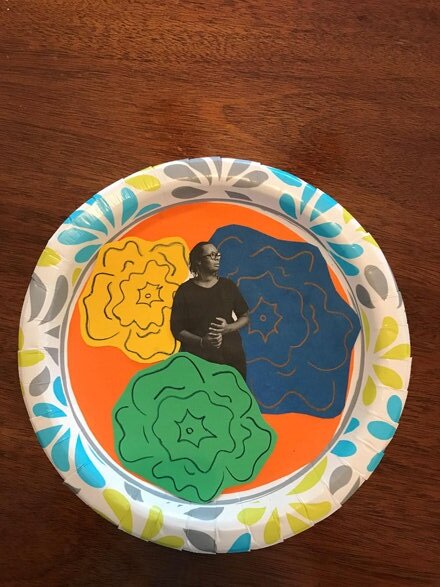

Here are some examples of our finished commemorative plates:

This plate commemorates William Morris (1834-1896), a wallpaper and textile designer, writer, artist, and socialist. Morris used nature and history as inspiration for his designs, so we’ve decorated this portrait of him with leaves cut from construction paper and copied a floral motif from one of his designs as well. Morris rejected the mass industrial production of his lifetime. He celebrated beautiful, well-made objects, thinking it better for workers to make objects of which they could be proud and through which they expressed themselves, rather than be merely part of a factory. He wrote “I do not want art for a few, any more than education for a few, or freedom for a few.”

This plate celebrates contemporary artist Mickalene Thomas (1971-). She uses photography, paint, mixed media, and collage. She often references pop culture, particularly 1970s textiles, in her work, and surrounds representations of her community with these images in order to explore questions of identity. We’ve surrounded a portrait of Thomas herself with the style of flowers often found in one of her pieces in the bold colors she favors.