By Philip Zea

President and CEO

Timekeeping is the measurement of elapsing time. Humans are drawn to timekeeping “up to the minute” because we are self-important with “no time to waste” and because we are driven to master our surroundings through the manipulation of machinery. These foibles include achieving precise timekeeping even though a few seconds here and there make absolutely no difference to our lives other than being wrong. The irony is that we do not control timekeeping; it controls us. Our cell phones are the new-age pocket watches with a chokehold on us that demands daily therapy. For some, retirement is the only hope.

Even though some observers assume that the Connecticut River Valley was hopelessly “behind the times,” the first clock was owned in Deerfield at the close of the 17th century Deerfield attorney, John Catlin, Jr. (ca. 1643-1704), who died during the 1704 raid, owned a “house clock” appraised in his probate inventory at 35 shillings—a huge sum for any domestic object at the time. More of a status symbol than perhaps an accurate timekeeper, Catlin’s clock was the only one in Deerfield, so far as we know, and was likely snatched from the flames because if it. Personal timekeeping in any part of the English-speaking world remained a luxury until the 1810s. By then, Connecticut was on the threshold of becoming the clockmaking capital of the world thanks to entrepreneurs like Eli Terry (1772-1852).

The extensive probate study undertaken during research for the 1984 book and exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum, The Great River: Art & Society of the Connecticut Valley, 1635-1820, found only a handful of mechanical clocks (6% of decedents) in the entire region before the Revolution, the earliest being Henry Packs (Parks?) of Hartford who died in 1640. By the end of that century, John Catlin’s clock in Deerfield was a great rarity at a regional level, let alone the local one. Even at the close of the following century, the 1798 Direct Tax records show at most only one household in twelve owning a clock. For most people, timekeeping continued to follow ancient and natural forms, like the daily path of the sun, the monthly passage of the moon, changing seasons, menstrual cycles, and shifting tides. While few people used the precision of clocks to guard against idle time, hours were nevertheless a valuable commodity. Even as early 1633, the General Court of Massachusetts proclaimed, “No person, householder, or other shall spend his time idly or unprofitably.” There has never been rest for the weary.

Historic Deerfield owns the earliest extant tall clock made in the Connecticut River Valley. Seth Youngs (1711-1761) made it about 1740 in Hartford five years after he emigrated from Long Island. Like many clocks of the time, it runs for a day (roughly thirty hours) and amazingly was fitted with a mechanical alarm that could be set to arouse the household. (A harried owner dismantled the alarm long ago.) On view upstairs in the Ashley House at Historic Deerfield, the clock looks like English examples with a small hood and base and long waist in the proportions of a column. Inset into the waist door is a round glazed window so that admiring onlookers can see that the clock is fitted with a 39” pendulum rod. Introduced in the 1670s to replace the 9 ¾” rod invented by the Dutch astronomer and clockmaker, Christian Huygens (1629-1695), in 1657, the longer pendulum improved accuracy to a matter of seconds each day (well, maybe). Youngs’ confidence in his clock may have lagged, however, since he fitted it with only a single hour hand in the 17th century style to mark the passage of quarter hours.

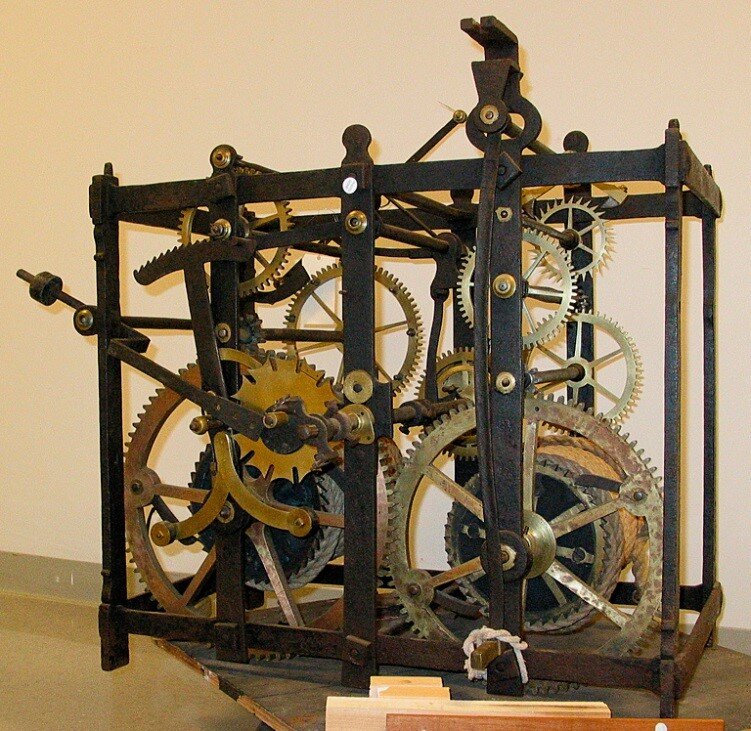

The public sphere of timekeeping was the real legacy of clockmakers for centuries. Like other early clockmakers in New England, Seth Youngs also built public timekeeping devices. In one instance, he constructed an elaborate (apparently) sand hourglass for the pulpit at the First Church of Hartford at the enormous cost of £5.10.0 in 1739. However, Young’s hourglass is but a speck against the influence of the earliest extant mechanical clock in the world which still runs at Salisbury cathedral in England after its first, booming ‘tick-tock’ in 1386. These tower clocks, or public clocks, met universal needs for everyone—young and old, rich and poor—and they demonstrated the status and wellbeing of the entire community in the Old World and then the New. That time came to Deerfield in 1744 when the Town of Deerfield decided to install a public clock on the 1729 meeting house on the Common just south of the 1824 Brick Church. Native son, Obadiah Frary (1717-1804), who lived in Southampton, Massachusetts, was commissioned to make the clock, which survives today in the Memorial Hall Museum. A complete tower clock of unknown origin dated 1787 is also owned by Historic Deerfield.

Although clock ownership was rare, clock influence as a statement of status was not. A year after the 1798 Direct Tax, Asa Stebbins (1767-1844) constructed his brick house—the first in Franklin County—on The Street in Deerfield. Because “time is money,” Stebbins bought a large, beautiful, and symbolic tall clock from famous clockmaker Aaron Willard (1757-1844) in Boston, where Stebbins represented Deerfield in the General Court. While the movement is basic aside from the larger size of the dial, the case was a special commission, probably made by the Dorchester cabinetmaker Stephen Badlam (1751-1815) who proportioned it to fit Stebbins’ North Parlor where the clock still stands today. While the clock tells time, it really tells the story of consumerism and our personal struggle with time even in small, rural towns like Deerfield where “time remains of the essence” with its own layers of significance in local history.