By Richard D. Little

Professor Emeritus, Greenfield Community College

Part 1

For a fairly short river, the Deerfield exhibits quite a number of intriguing features that are commonly misunderstood or unexplained. The river starts in southern Vermont and runs 73 miles to join the Connecticut River at the Deerfield – Greenfield border. Along the way the Deerfield traverses very different and dramatic landscapes, all a heritage of our region’s rich geologic history preserved in the underlying rocks. There are significant changes in geology along the way. Sometimes the bedrock is hard metamorphic and igneous types, and in other places it is softer sedimentary rocks like shale, sandstone, and conglomerate. In the hard rock areas, located upstream, the Deerfield Valley is narrow, a canyon even, with the river flowing within thousand foot high walls. This is just the place to create dams. Over the past 100 years 10 hydropower dams have been built. That’s a dam every 7 miles on average, for its entire length, making the Deerfield River’s water some of the most heavily used in the country.

Deerfield would have been under the glacial lake between 16,000 and 14,000 years ago, with the glacier front melting back each year.

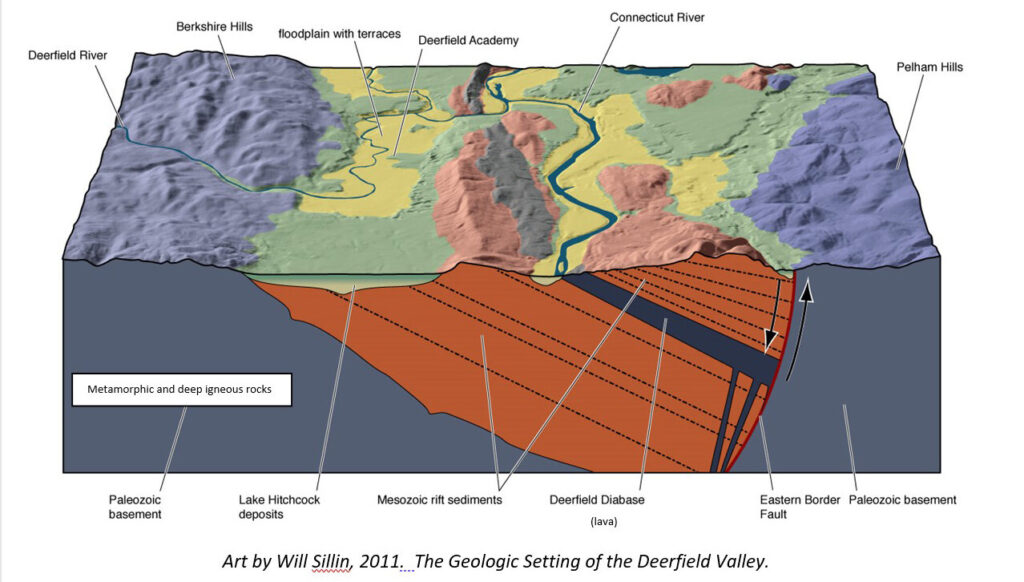

Farmland is what the lower Deerfield is most famous for. Here the valley is wide and flat with no stones of note, so the landscape really favors the plow. The underlying geology here is composed of the weak sedimentary “red rock” strata. These lowlands were eroded by glaciers and then covered by glacial Lake Hitchcock as the ice melted. The muddy and sandy deposits of the lake, as well as later river floodplain deposits, form the excellent terraced landscape that make up the Deerfield Academy campus and Historic Deerfield surroundings and is the productive base for fertile soil development.

Why is the lower Deerfield River valley so different with rocky steep upstream canyons to downstream floodplains? To solve this mystery, we need to view into the depths of geology time, back to the Paleozoic Era 500 million years ago.

During the early Paleozoic, North America’s shoreline ended near the eastern New York border. New England was not even part of our continent. However, New England is coming! It’s coming in several pieces, called exotic terranes. These terranes are big islands of Earth’s crust that, through the process of plate tectonics, collide with North America, adding to its real estate. Each collision results in mountains, culminating with the impact of Africa and Europe which created the supercontinent of Pangea. Bedrock was squeezed upward to form the Himalaya-sized Appalachian Mountains. The compression and heat of these orogenic events transformed our bedrock into metamorphic rock types such as gneiss, schist, slate, and marble. Occasional deep magma chambers cooled slowly to crystallize into granite. These geologic processes typically create very hard, erosion-resistant rock. The landscape records their unwillingness to yield to the forces of degradation by standing tall and steep. This is the origin of the canyons and rocky riverbed of the Deerfield’s upper valley as it cuts through the hard rock of the Berkshire Hills.

Before we get to the lower valley’s flat landscapes, let’s look at a prominent mystery that has captivated many: the Shelburne Falls “Glacial Potholes”. These beautiful rocky outcrops are nicely exposed due to a dam that diverts the Deerfield’s water. Dozens of circular erosion features called potholes are displayed including one that has been called the world’s biggest. Well, first of all, potholes are due to the action of water flow that twirl stones in the holes, drilling them deeper. Potholes have circular rims. Glaciers are not involved with their formation, and in the Shelburne Falls case, not even glacial melt water flow. We know this because of glacial Lake Hitchcock. During Lake Hitchcock time (about 16,000 to 14,000 years ago in this area) the Shelburne Falls potholes were covered by Deerfield River sediment, portions of a delta that was built into the old glacial lake. The potholes could not have started until the lake drained, allowing the Deerfield to erode its channel down to the future potholes bedrock. By the time Lake Hitchcock drained about 14,000 years ago, glacial ice was long gone from the Deerfield Valley, so neither ice nor its melt water could have been involved in the pothole excavation. The flow of the Deerfield, powered by rainfall and gravity, did the work, and it took 14,000 years to create this sculptured masterpiece. So, the famous “Glacial Potholes” are not glacial, but river potholes, and one of the prettiest sights in New England.

Do you know the difference between these two river-eroded holes: potholes and plunge pools? The biggest Shelburne Falls hole is 39 feet across and is claimed to be the biggest “pothole” ever found. However, this large hole is a plunge pool, not a pothole. [Also, a quick internet search will reveal bigger true potholes.] Plunge pools are carved at the base of waterfalls by the force of the fall. They do not have level circular rims like potholes. While the potholes form by the drilling action of swirling stones as the stream water flows, the plunge pools are due to falling water. They erode much like a jackhammer impacting the bedrock at the base of the fall.

“Glacial” potholes in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts.

End of Part 1.

Richard D. Little, Professor Emeritus, Greenfield Community College, Greenfield, MA. has taught at Deerfield Academy, and done programs at Historic Deerfield for many years. He will be one of the lead geologists at Historic Deerfield’s “The River, Drifting Continents, Dinosaurs, and a Glacial Lake: Understanding the Amazing Stories Preserved in our Rocks and Landscape” July 12 – 16, 2021. He is the author of Dinosaurs, Dunes, and Drifting Continents: the Geology of the Connecticut River Valley, and leads “Fantastic Landscapes” tours to outstanding North American locales. His web site is EarthView.rocks (http://earthview.rocks). For comments and questions he can be reached at rdlittle2000@aol.com.