Created by Historic Deerfield Museum Education Staff Members, Claire Carlson and Faith Deering.

Welcome to Week Six of Maker Mondays from Historic Deerfield. Check your social media feed or look for an email from us every Monday for a fun activity that you can do at home, inspired by history and using common household items.

This week’s Maker Monday is part two of Making and Keeping a Journal.

Download a printable PDF of this activity.

Writing in the Journal/ Using the Journal You Made

Last week we explained how to make a journal. We hope you were successful and had fun: maybe you have started writing, drawing or making notes in your journal. This Maker Monday we would like to introduce you to some ideas about journal keeping.

The word journal comes from the French word jour, meaning day. The practice of writing daily observations in a blank book is long-standing. People have long written about their daily activities, recorded temperature and weather conditions, and noted current news and family events. Some journals are still read hundreds of years after they have been written. Reading such an old journal gives the reader insight into a personal view of the past. These journals become important historic records for daily life and reactions to major events–the events may be well-documented, but, without sources such as journals, how ordinary people thought about them are not as well known.

Were you wondering about differences between a journal and a diary? We had the same questions and set about finding some answers. The first place we looked was in a dictionary to get some definitions. In the process we found there are other names for handwritten books, some of the names are no longer used, but once were very popular We learned about daybooks and commonplace books. We also knew there were some important journals in the archives in our collection. We want to share some images and excerpts from these very special books.

Here are some definitions we found useful:

A Journal is a written record of experiences and observations. With journaling, there are no rules: you’re in charge. Some journals have a specific purpose. For instance, a nature journal can be used for recording natural events such as the weather, the blossoming of flowers, bird sightings. Nature journals have also been used as places to press flowers and leaves. Travel journals record observations on a journey, while creative journals store ideas and notes for future use. The classic image of a journal may be a leather-bound notebook. So you can channel history and write with a fountain pen in a leather-bound book if that inspires you, or with a pencil in the simple paper and stick-bound journal you made last week.

A Diary: This can be thought of as a place where you record personal events, emotions, thoughts or feelings. A diary is often more autobiographical than a journal. Historically, diaries have been an important place for recording reactions of social and political events of the day. People have also kept spiritual diaries, charting their own internal changes and regular spiritual practices. In British English, a diary also often refers to a book that records engagements and meetings which in American English would more often be called a calendar, day-timer, or organizer.

A Commonplace Book: This is an older version of a research journal. They became popular in the seventeenth century and were used like a scrapbook to store summaries of whatever the maker had read, quotations, recipes, notes from sermons, remedies for illness–whatever information needed to be gathered and stored! One goal of a commonplace book was to harvest a collection of wise statements for further meditation. The key was to write the words down by hand, for by carefully and laboriously copying the insights of great thinkers, one could absorb and internalize their wisdom. More practically, they helped people remember what they had read and learned.

A Daybook is a book in which the transactions of the day are entered in the order of their occurrence. These entries can be very brief–perhaps only a single line. Over time, however, it becomes possible to compare different years and understand the seasonal rhythms. This could be a useful reference for a busy farm in early New England, or even a good record in a modern office, helping its keeper anticipate regular tasks.

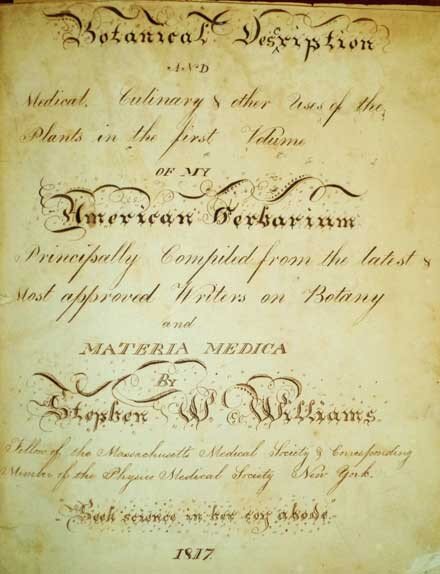

The things that people record in private diaries, daybooks, sketchbooks, commonplace books, or journals offer glimpses into the past and daily life that are fun to read and research. Historic Deerfield, and our sister organization, the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, are fortunate to have many examples of these works in the manuscript collection housed at the Memorial Libraries. These include a copy of a commonplace book kept by Jonathan Belcher written in 1727, an herbarium of plants collected by Dr. Stephen West Williams in 1817, the sketchbooks and journals of Epaphras Hoyt written between 1820 and 1849, and the diary of Elihu Ashley kept between 1773 and 1775.

Williams Herbarium

The Williams Herbarium is one of the very special items in the special collections at Historic Deerfield. It has been digitized and is accessible to view online: https://archive.org/details/herbarium0000will/page/n117/mode/2up

An herbarium is a collection of dried plant specimens mounted on sheets of paper. The plants in an herbarium are carefully collected in the place where they are growing. The plants are identified and labeled, then pressed and mounted on archival paper. Collecting plants and making an herbarium continues to be important work for botanists. Most major natural history museums and universities have herbaria. These collections are used by botanists in their research.

Historic Deerfield has a valuable herbarium made by Dr. Stephen West Williams (1790- 1855) During the summer of 1816, Dr. Williams gathered plant specimens from locations around Deerfield. He identified the plants, pressed and mounted them so could learn about their medicinal properties. He later wrote a book describing the ways in which the plants could be used to prepare medicines. The blog post below is about American ginseng and uses images from the manuscript that Williams wrote to accompany the herbarium.

https://www.historic-deerfield.org/blog/2017/9/29/the-root-of-the-matter?rq=williams%20herbarium

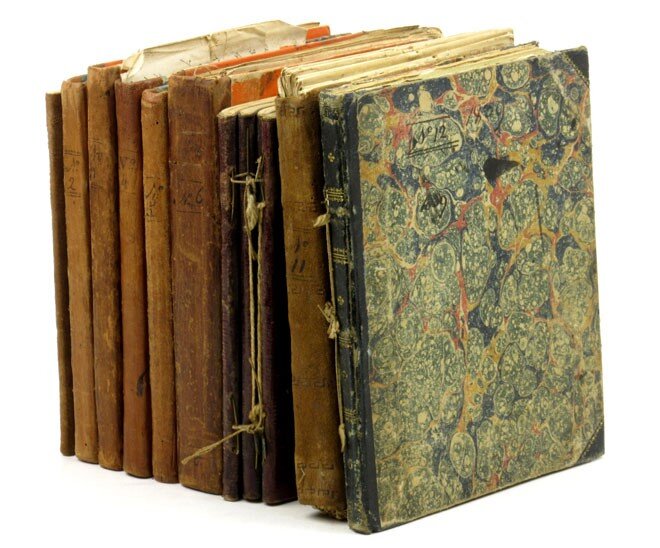

Hoyt Journals and Sketchbooks

Epaphras Hoyt was born in Deerfield in 1765. He was very involved in town affairs and served as postmaster and justice of the peace, and a term as the county sheriff. He was also a skilled surveyor. His journals and sketchbooks were written over a two-decade period and provide glimpses into his opinions and remembrances of growing up and living in Deerfield during the late 18th and first half of the 19th centuries. You can read more about the Epaphras Hoyt collection in this blog post.

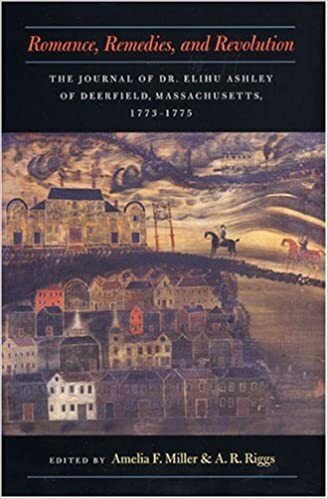

Elihu Ashley Diary

The Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association owns a diary kept by Elihu Ashley that is dated between March 1, 1773 and November 5, 1775. It was published as Romance, Remedies, and Revolution : the Journal of Dr. Elihu Ashley of Deerfield, Massachusetts, 1773-1775 in 2007 and edited by Amelia F. Miller and A.R. Riggs. The diary is filled with information about Elihu’s daily activities and how he felt about them. It offers a glimpse into the mind and feelings of a young man, studying to be a doctor, courting his future wife, and his connections to friends and relatives on the eve of the American Revolution.

Final Thoughts

We hope you have enjoyed these two weeks of journal making and writing. Have you said to friends or family “I am keeping a journal”? These are challenging times we are living in, so a journal kept now could become an important historic document for future generations. …. Your journal will also be a personal record for you to read and reflect on when you look back at the spring of 2020.

Please share a photo of your stick-bound journal with us by sending it to historicdeerfield@historic-deerfield.org