By Heather Harrington

Associate Librarian

As the COVID-19 pandemic rages across the world, it is important to remember that this is not the first pandemic the world has faced. Often the 1918 influenza is mentioned as the last great world-wide pandemic. While this is true, an earlier pandemic of cholera from the 19th century as documented by Epaphras Hoyt (1765-1850) of Deerfield, shows that our reactions to the disease are very similar to Hoyt’s.

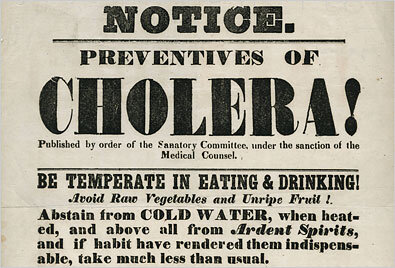

Cholera, a bacterial disease spread mainly through contaminated water, has been around for centuries. Periodic outbreaks and pandemics over the years have occurred on almost every continent. What made the disease particularly terrifying in the nineteenth century, was that no one had discovered how it spread from person to person, or place to place. People were left to speculate on their own.

In the 1840s, a new pandemic of cholera began to spread, starting in Asia, and making its way to Europe, and eventually North America. Epaphras Hoyt, a Deerfield resident and a devoted journal writer, tracked the spread of the disease. Like everyone else, he did not know what caused the disease and read every newspaper and pamphlet he could find that talked about it. For him, knowledge was power. The more he knew about cholera, the better prepared he felt to deal with it. In 1848, the disease had arrived in New York City and New Orleans. He chronicled in his journal for that year, reports of how many had died, and where the disease had spread to that week. He noticed that the disease seemed to follow major waterways, up the Mississippi and along the Hudson River. His fear was that the disease would travel up the Connecticut River and arrive in Deerfield. Hoyt, being in his eighties, probably felt vulnerable to the disease, should it arrive.

To better understand cholera, Hoyt read the opinions of two doctors, a Dr. Jackson, and a Dr. Meigs. Dr. Jackson proposed that cholera was related to a certain type of rock formation and soil combination that released the harmful disease into the air. He suggested that New England was safe, as the area did not have this rock or soil. Hoyt found this idea questionable. He was not convinced cholera came from the soil.

Dr. Meigs offered up a cure for cholera. He sold pills that cured the disease if one followed an elaborate series of steps and swallowed a large number of pills, and immediately rested afterwards. Hoyt was rightfully skeptical of this approach and was not inclined to test it out.

By 1849, when the disease seemed to be at its peak in the area, Hoyt considered moving to Rowe, Massachusetts. Rowe had fresher air and was a healthier place to live. He based this idea on its small population size, its location on higher terrain, and its lack of reported cases of any disease. Yet Hoyt being a loyal, life-long Deerfield resident, did not move.

With all of his research on cholera, Hoyt did come to realize that cases increased near large sluggish rivers and lakes in the interior of the country. He thought this might be part of the cause of the disease. It was not until 1854 that John Snow discovered that cholera spread through consuming contaminated water.

While Hoyt and Deerfield came out of the pandemic relatively unscathed, others were not so lucky. Former President James K. Polk died of cholera in 1849, becoming the country’s best know victim of disease.

Our reactions today to COVID-19, following the latest news, trading rumors about cures, worrying about the spread of the disease, and general fear of the unknown are natural responses to a global pandemic. Epaphras Hoyt had the same reactions to the cholera pandemic of the 1840s. Today cholera is not such a scary disease. We know what causes it, how to prevent it, and how to treat it successfully. A cholera pandemic occurring today seems unlikely. With the speed of modern medicine and the advancement of knowledge, soon COVID-19 will become like cholera: a disease we can manage and control, that does not cause world-wide panic.

1 All references to Hoyt’s activities come from Epaphras Hoyt, ”Sketch-book no. 21-23, 1847-1849,” Historic Deerfield Library (Deerfield, MA)