By David Bosse, Librarian and Curator of Maps

Broadsides – single sheets of varying sizes printed on one side only – have been produced since the beginnings of printing in the West, with papal Bulls among the earliest examples. The Oxford English Dictionary notes the first use of the term in England as occurring in 1575. Also referred to as broadsheets, or handbills in the case of small examples[1], this printing form typically appears on a lower grade of paper as befits its largely ephemeral nature. Not unlike small posters announcing concerts or meetings that we encounter on utility poles and bulletin boards, these items would be posted in taverns, in shop windows, on doors, and in other public locations.

Today, some fine press printers issue limited edition, highly collectible broadsides that sometimes are printed on exquisite hand-made paper. As a museum we collect broadsides and handbills of a more common variety, but that reveal something about the time and place of their making. The topics range from government proclamations to commercial promotions, and address many matters in between, such as poetry and ballads, and news bulletins. In terms of visual culture, some broadsides are dazzling examples of the typographer’s art, while others couldn’t be more simple. Those that contain graphic imagery are particularly appealing and instructive.

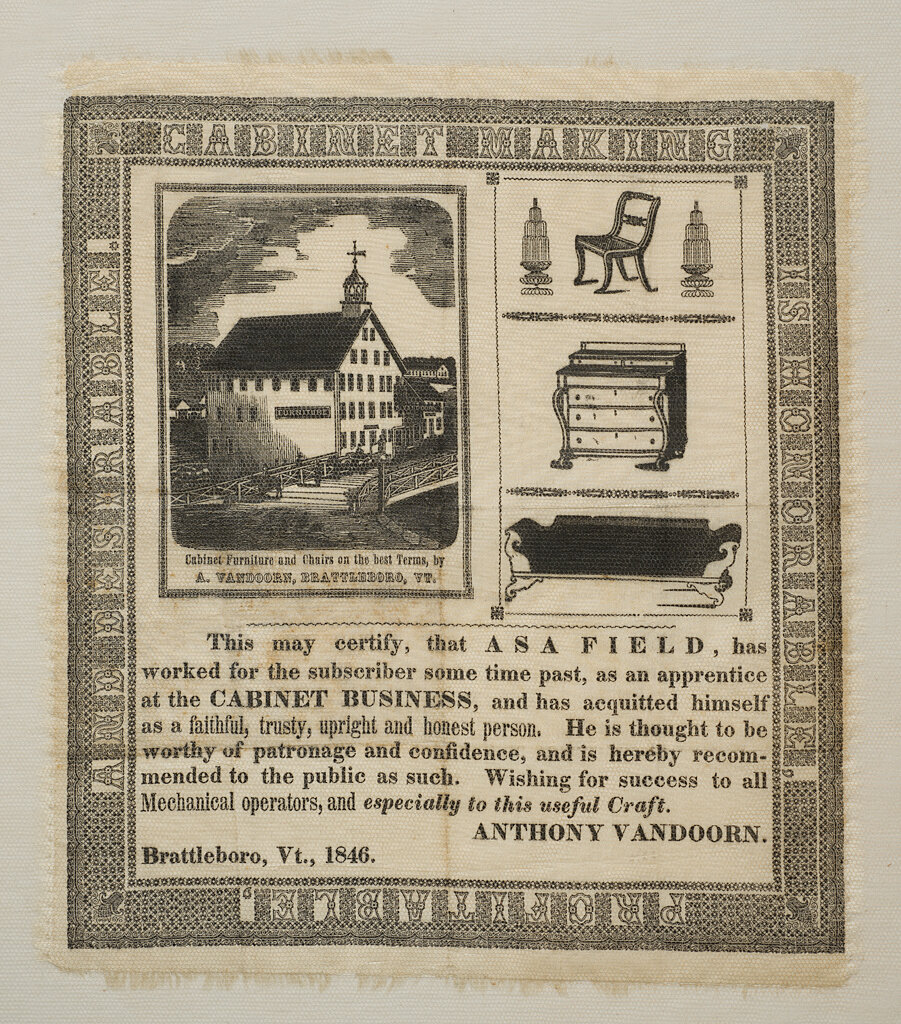

While most broadsides made use of low-quality paper, more refined printing surfaces are also encountered. One such example in our collection is attributed to Anthony Van Doorn who opened a cabinetmaking shop in Brattleboro, Vermont. In 1830, he relocated to Main Street near the town’s commercial center where he operated the largest furniture making establishment in Vermont until 1851, when he sold his business.

In 1846, the furniture maker had a small broadside printed to praise the work of his apprentice, Asa Field, who was about to strike out on his own. Presumably printed in Brattleboro, possibly by the press of the Vermont Phoenix located just a few doors away, the broadside includes a decorative border, a large image of Van Doorn’s factory, and three images of types of furniture made there. Historic Deerfield owns two pieces of Van Doorn furniture, which adds further interest to the broadside. Paper copies may have also been produced, but this example on silk is the only known institutional copy of the broadside to have survived.

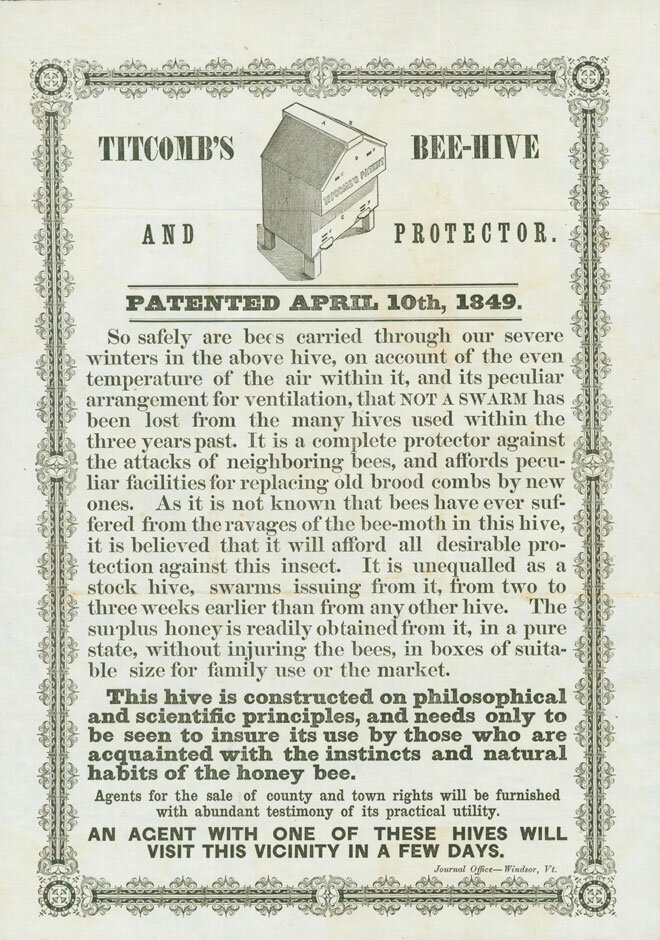

Commercial ventures typically heralded their launch in the pages of a newspaper in order to reach a wide audience. The size constraints of advertisements, particularly in the pre-offset rotary printing[2] era, led some entrepreneurs, however, to issue larger-format broadsides. For example, in the spring of 1849, Titcomb’s Bee-hive and Protector, extolling the virtues of Stephen Titcomb’s design, appeared. Constructed on “philosophical and scientific principles,” the hive protected bees from attack by flying insects, and the ravages of winter. Our copy of Titcomb’s Brief History of the Honey Bee, also printed in 1849, includes eight figures detailing the hive and its operation. The broadside credits the press of the Vermont Journal in Windsor, Vermont.

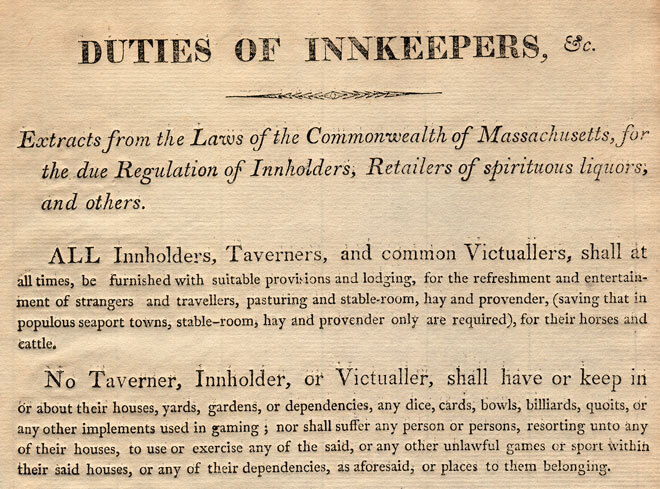

Local printers looked for work from any quarter, and vied with one another to secure lucrative government contracts to produce statutes, proclamations, commissions, and forms. Items such as these were often sent to local officials for them to act upon as required. Some statutes had a life outside of the pages of the published Acts and Resolves, as in the case of Duties of Innkeepers, &c., extracted from existing Massachusetts law dating from 1787. Printed in circa 1810, the broadside details the responsibilities of proprietors and retailers of alcohol. These include a prohibition on dice, cards, billiards and other “implements” of gaming, dancing, drinking by minors (with the exception of travelers), and restricting activities on the “Lord’s Day.” Someone operating a tavern could have posted Duties as a way of trying to regulate the behavior of patrons as demanded by a higher authority.

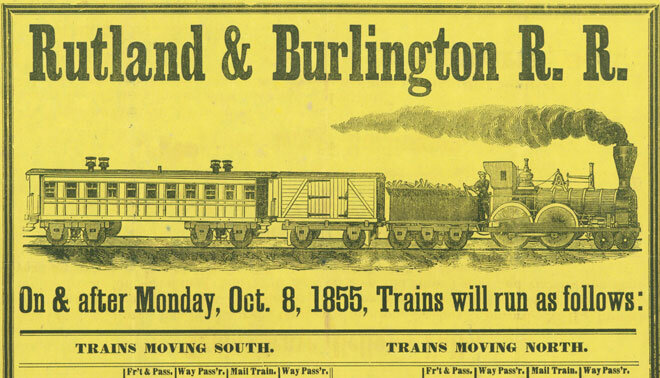

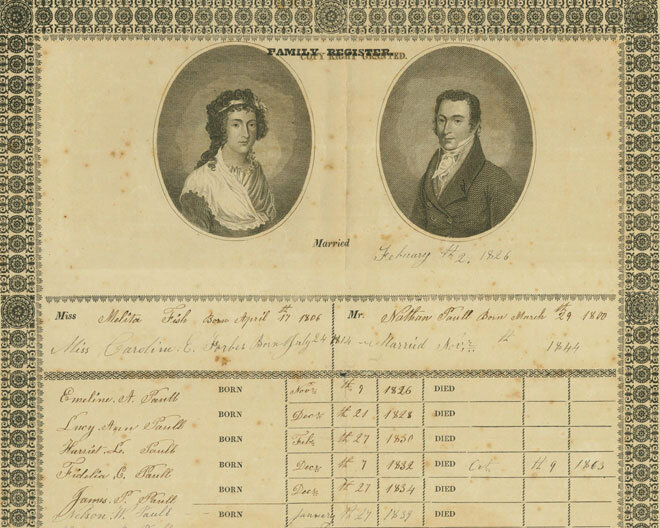

Posted handbills and broadsides often served as announcements of events, or public schedules. Fairly typical among these are railroad timetables such as that of the Rutland and Burlington Railroad which operated for more than a century. While hundreds of copies would have been printed, most did not survive. Other examples of the broadside form took on personal significance, and thus departed from the realm of ephemera. The purchaser of the Family Register, printed in Northampton, Massachusetts, in circa 1825, would fill in the names of family members below the generic images of a husband and wife – in this case Nathan Paull and his two wives, Melita Fish and Caroline Forbes, and their children.

From royal proclamations to comic satires, broadsides, broadsheets, and handbills have caught the public’s attention for centuries. Today they document historical moments, serve as examples of printing and visual culture, and provide a window on the concerns of the day.

[1]. Some early newspapers are referred to as broadsheets, but comprise a different category as do ‘handbills’ printed on both sides and possibly folded.

[2]. The rotary press developed in the 1840s, facilitating the printing of large, continuous rolls of paper; offset printing, which better accommodated images, began in 1875.