It has been said that the wild ginseng root (Panax ginseng) possesses healing and revitalizing properties. The name of its genus is derived from the same Greek word that gave us panacea – a cure all. Continued belief in ginseng’s efficacy is reflected in the fact that one can easily find it on the shelves of organic food markets and even chain grocery stores, usually as a dried supplement in pill form.

Throughout the world, but particularly in Asia, the root is sold in less processed forms in open-air markets and by apothecaries.

Although North American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) was considered inferior to the species native to Manchuria and Korea, it nevertheless found a ready market as a commodity in the China trade. From as early as 1719, Canadian ginseng had been shipped to China by French merchants.

In western Massachusetts, the Rev. Jonathan Edwards of Stockbridge noted the collecting of ginseng by local Native peoples. Writing to a ministerial colleague in 1752, Edwards complained that traders in Albany had induced “our Indians of all sorts, young and old, to spend abundance of time in wandering about the woods…in the neglect of public worship and of their husbandry; and also of their going much to Albany (which proves worse to them than going into the woods) to sell their roots.”

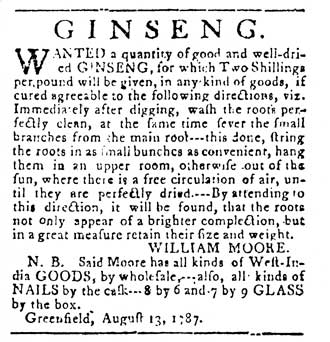

New England shopkeepers purchased ginseng from local gatherers and then sent the root to Boston and Salem merchants for export to China after direct trade was established in 1784. The Chinese accepted little in trade from the West; ginseng and silver being most desirable to them. In return, American ships brought back cargos of tea, silk, and ceramics.

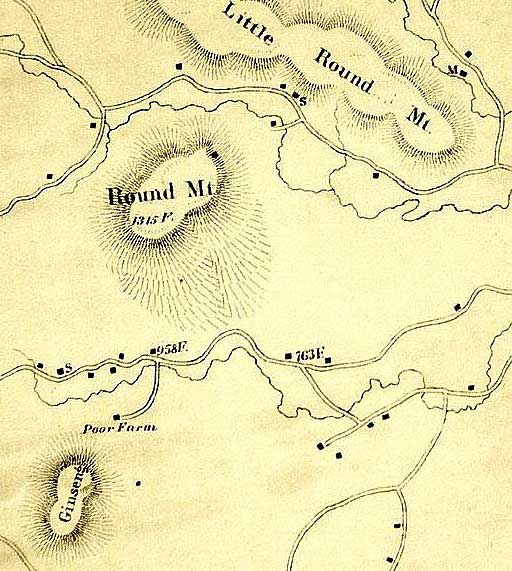

Ginseng grows in shady, deciduous forests throughout the Connecticut River Valley; collecting the plant typically occurs in the fall. The plant’s commercial value led to overzealous harvesting and its present relative scarcity, although local place names such as Ginseng Hill attest to its presence. But not all plant hunters sought out ginseng to directly profit from it.

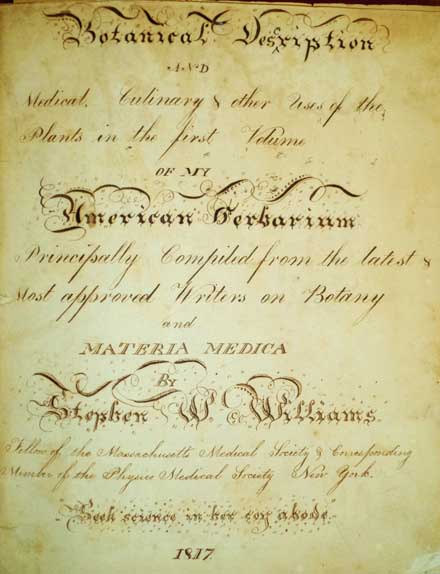

Stephen West Williams (1790-1855), the third generation of Williams physicians in Deerfield, began practicing medicine in 1813 after attending Columbia College in New York. Along with Dennis Cooley, an apprentice to Williams’s father, Dr. William Stoddard Williams, and Deerfield Academy preceptor (i.e., headmaster) Edward Hitchcock, Stephen West Williams began prowling the woods and fields around Deerfield collecting plant specimens in 1817.

We know from his writings that the plants’ medicinal and culinary uses held the greatest value for Williams. In all, he gathered more than 500 specimens which he assembled into an herbarium, a fairly common practice at the time.

Accompanying the herbarium, Williams prepared a “Botanical Description,” a 300-page bound manuscript that discusses the medical and culinary uses of the plants, and often notes where he found them. Harriet Goodhue (1800-1874), then just 17 and a student at Deerfield Academy, made numerous watercolor renderings of the plants to illustrate the manuscript. For all we know, she may also have collected some of specimens. Harriet Goodhue and Stephen West Williams married in 1818, and eventually moved to Illinois where they are buried in Durand. Both the manuscript and the herbarium that they worked on are in the Historic Deerfield Library collection.