Arthur Wellesley Hoyt was born in 1811, the first and only son of Epaphras and Experience Hoyt of Deerfield, Massachusetts. Arthur had three sisters, all quite older than him. At his birth, his father would have been very pleased to finally have a son to teach and pass his wisdom on to. Epaphras had waited almost 20 years for a son, and finally he had one.

Courtesy of Memorial Hall Museum

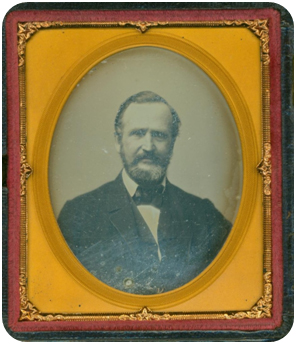

Epaphras Hoyt (1765-1850), a surveyor by trade, was a self-educated man who found science, mathematics, military history, and politics fascinating. He kept detailed journals of his thoughts on these subjects, the books he read, the scientific experiments he conducted, and recollections of his past journeys and trips. Seventeen of these journals have found their way into Historic Deerfield Library’s collection in the past couple of years. From these journals we know that Epaphras considered himself an “Enlightened man of reason.” His journals show how knowledgeable he was on so many subjects.

Epaphras wasted no time in educating his son Arthur. At an early age, Arthur accompanied his father on a surveying trip of the Hoosac Mountain area. Epaphras would let Arthur use the theodolite on occasion. Epaphras was training Arthur to be a surveyor like him, or, was possibly thinking grander thoughts, and decided surveying was a start of a much bigger career for his son.

This was not the only surveying job Arthur would help his father with. As he grew older, Arthur also accompanied his father on a survey of the Connecticut and Massachusetts border. At age 20, Epaphras got him a job working with Simeon Borden working on laying the base line in Massachusetts for the upcoming trigonometrical survey in 1831. Arthur would go on to have a lucrative career as a civil engineer, building several railroads, roads and canals. He would also invest in several mines and in building towns in the Midwest. By his own account, he was quite successful and was able to retire pretty well off. He died in Templeton, Massachusetts in 1899 at the age of 88.

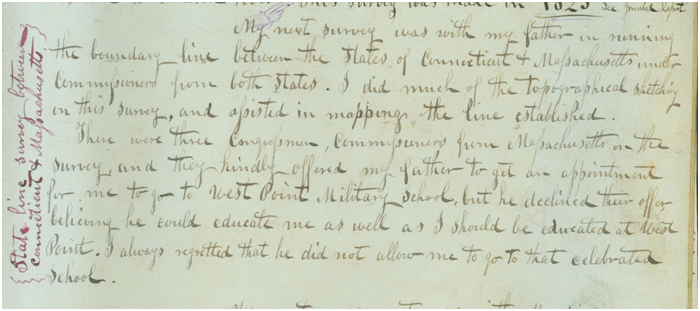

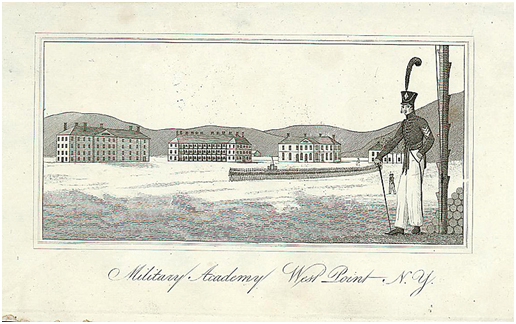

What was unknown about Arthur’s education and life as a civil engineer was that he once had the chance to go to West Point Military School. In an autobiographical summary of his civil engineering career, newly acquired by the Library, Arthur writes about this missed opportunity. While on the Connecticut border survey with his father, several Massachusetts Congressmen, part of the Boundary Commission, offered Epaphras an appointment for Arthur to the school. At the time (1826) West Point was known as an engineering school. Its graduates were building the nation’s railroads, roads and bridges. Seeing Arthur’s facility with surveying, and probably hearing of Epaphras’ dreams for his son, they offered the 15-year-old Arthur quite an opportunity. However, Epaphras refused. In Arthur’s words, “he declined their offer, believing he could educate me as well as I should be educated at West Point.”

Why did Epaphras refuse this offer? Was it because he couldn’t bear to part with his beloved son any sooner than he had to? For years, Epaphras kept track of Arthur in his journals, always concerned about sickness and disease, geography and politics where Arthur was. By keeping Arthur home with him, instead of sending him away, it would be less worrisome.

Was it hubris? Did Epaphras believe that he was the best teacher for his precious son? That no one could be better? Epaphras was quite intelligent and eager to teach and spread his knowledge to others. The son he had wanted for years was the perfect person to teach and build a legacy on. He, Epaphras, had to be the teacher, as no one else cared as much as he did.

Epaphras always had good things to say about West Point graduates in his journals. He always wished there were more of them to lead or train the local militias. He believed they received solid military training. Surely he did not object to the school itself. His reasons seem to be of a more emotional kind.

Whatever the reason, this decision to keep Arthur out of the school probably changed the course of Arthur’s life and may have even saved it. Had he gone to West Point, he may have still become a successful civil engineer, but he may also have become a successful military officer. West Point graduates served with distinction in both the Mexican War and the Civil War. Perhaps Arthur would have lost his life in one of those wars, instead of dying an old man. It is also possible he could have been the great general President Lincoln was always searching for in the first years of the Civil War. He could have been a legendary soldier.

Looking back, Epaphras would have been pleased with the trajectory of his son’s career. He likely had no regrets about turning down the offer. Arthur, however, did. In his autobiographical summary, he notes, “I always regretted that he did not allow me to go to that celebrated school.”