In 1888, the state of Massachusetts amended an earlier 1887 bill that required the documenting of all sales of arsenic and other poisonous substances. The new bill created a fifty dollar fine for violators, required all bottles and boxes to be labeled “poison,” and list an antidote, if any. The law further added specific items to the list of existing poisons. This law would only apply to retail stores selling such items without a prescription from a physician. Chemists and wholesale distributors were not subject to these regulations.

The reason for this law seemed to be an attempt to prevent accidental death, suicide or murder by poison. In the 19th century, death by arsenic poison was common all over the world, partly because of the availability of arsenic-laced insecticides. This law is an early example of attempted regulation of drug sales. It was not until the early 20th century that the federal government would begin regulating sales of pharmaceuticals, and poisons.

For general store keeper Amos L. Avery of Charlemont, Massachusetts, this meant he began keeping track of all of his poison sales in a log book. This book, along with his other account books, bills, receipts, and other business papers, have found their way into the A.L. Avery General Store Records in our Library Special Collections.

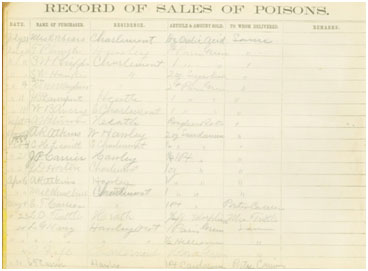

Avery’s book, made especially for this purpose, has a copy of the law printed on the inside cover. It begins in July of 1888 and lists the date, purchaser, residence, the article and amount sold, and to whom it was delivered. The majority of his clients are from the Charlemont, Heath, Hawley, and Rowe areas, with a few customers from Plainfield, and Savoy, father to the west. The sales are recorded regularly through 1899, and then sporadically through 1920.

His biggest seller was a product called “Paris green.” This green powder, also known as copper acetoarsenite, was used as an insecticide for produce, especially apples. It had a secondary use as a pigment for paint. Some customers bought several cans of the powder, either for a large infestation problem, or many apple trees, or a big need for green paint.

Avery also sold sugar lead (known as lead acetate today), a product still used in hair color and dyeing; oxalic acid, a bleaching agent and a parasite killer for beekeepers; laudanum, an addictive opiate used to treat coughs, colds, diarrhea, sleeplessness, and many other diseases; morphine; hellebore, a plant used to treat paralysis, gout, and insanity; chloroform; strychnine, a pesticide used for killing birds and small animals; a substance he called “bed bug poison”; and the nationally popular poison, “Rough on Rats,” a combination of arsenic and coal used for killing household vermin. His sales were seasonal, selling the majority of the laudanum and morphine during the fall and winter months, and selling the majority of the insecticides and rodent poisons during the months of June and July.

Avery’s sales indicate just how prevalent rodent and insect infestations were in the 19th century, and how ignorant people were of the dangers these products presented. Today the dangers of arsenic, morphine, strychnine, and lead are well known. When was the last time you bought insecticide or rat poison and had to record the quantity for the government? This law was the state’s attempt to educate consumers about the dangers of the products they were buying, along with an attempt to provide evidence in a future crime. While record keeping still exists for some explosive or flammable materials, laws like this no longer protect today’s consumers. This poison sales book, and others like it, remains a peculiar remnant of a different time.