Like most other artisans, engravers normally learned their craft by working with a practitioner. The journey from apprentice to master was circuitous, involving a number of stopovers along the way. For example, John Fitch (1743-1798) of Windsor, Connecticut, began his practical training by learning to survey under his father’s tutelage. Thanks to his unpublished autobiography, more is known about his early instruction than that of many of his contemporaries.1 Fitch next served an apprenticeship with local clockmaker Benjamin Cheney, before traveling to Trenton, New Jersey, where he worked as a journeyman clockmaker, gunsmith, and silversmith. In each of these occupations he combined mechanical expertise with an ability to engrave decorative features and text. Fitch’s graphic skills were on full display when he cut the copperplate for his large Map of the North West Parts of the United States of America (1785).

The careers of many early American engravers are represented primarily, or even entirely, by their work. It seems reasonable to assume that these largely undocumented artisans received training somewhere along the line. Those who achieved recognition, whether by their work or their deeds, may have become the subject of biographical notice. One such engraver was Jonathan Hale Goldthwait (1811-1870) of Longmeadow, Massachusetts. In producing a family history, one of his descendants shed some light on Goldthwait’s early work.2At the age of 17 he went to Boston where he apprenticed with a bank note engraver. Numerous engraversoperated in Boston when Goldthwait arrived in 1828; those known to have done banknotes include Annin & Smith, John Ritto Penniman, John Ruben Smith, William Hoogland, Thomas Wightman, George Graham, and Reed, Stiles & Co. Jonathan Goldthwait could have apprenticed with any of these individuals or firms.

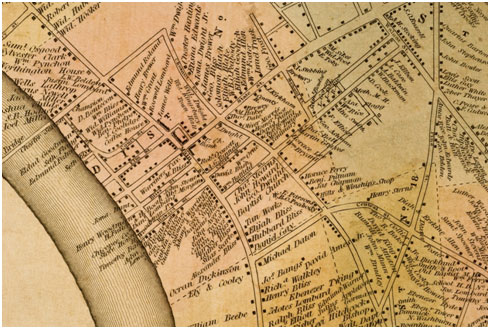

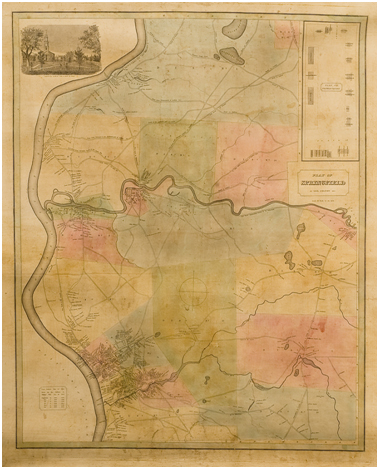

Jonathan Goldthwait remained in Boston at least until March 1834, when his name appeared on a memorial of citizens of that city to the federal government decrying currency devaluation and calling for the creation of a national bank. He next appears in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he engraved a large (32 x 25 inches) wall map of that town, done by his cousin, George Colton (1793-1839).3 Colton, a merchant who held a number of town offices, was married to the niece of Epaphras Hoyt, the sage of early 19th-century Deerfield. The engraving of this map in the Historic Deerfield collection (HD 2012.7) exhibits minuscule lettering and fine line work that became a hallmark of Goldthwait’s style.

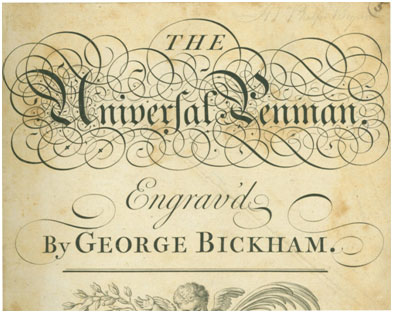

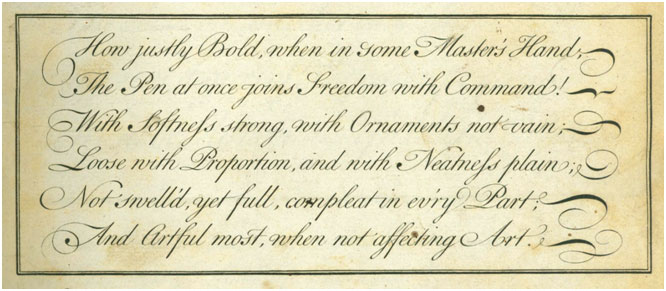

Beyond their initial training, craftsmen might gather printed sources that helped inform their work. One example of this at Historic Deerfield is a copy of The Country Builder’s Assistant (Greenfield, MA, 1797) owned by carpenter and cabinetmaker William Mather (1766-1835) of nearby Whately, Massachusetts. To this can be added a pattern by George Bickham printed in London in 1743, at one time in the possession of Jonathan Goldthwait.4 While Bickham’s folio of 212 leaves of engravings was designed as a penmanship exemplar, its depiction of lettering styles, flourishes, and decorative imagery would also have served as useful models to an engraver. Mastering one’s craft typically included knowledge of different fonts and italics, which presumably is why Goldthwait purchased the book. Apparently he obtained it in Boston in 1833 at what may have been considerable cost.

Detail of title page of Bickham’s pattern book, and Jonathan Goldthwait’s signature of ownership.

Detail of a page from The Universal Penman

The author of the Goldthwaite genealogy described Jonathan Goldthwait as “an artist in temperament, possessing a very intuitive sense of the beautiful and of the incongruous, and his fine taste and excellent judgment in such matters were very much sought and valued.” His ownership of The Universal Penmangives credence to that claim.

[1]. The American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia) owns Fitch’s manuscript and published a transcription of it in 1976.

[2]. Charlotte Goldthwaite, Goldthwaite Genealogy: Descendants of Thomas Goldthwaite, an Early Settler of Salem, Mass., (Hartford, 1899), 224-28. Jonathan Hale Goldthwait apparently never added an ‘e’ at the end of his name.

[3]. For a discussion of the map see David Bosse, “The Earliest Printed Maps of Springfield, Massachusetts,” Imprint, Vol. 40, no. 1 (2016): 15-25.

[4]. Bickham’s book is on long-term loan to the Historic Deerfield Library by museum trustee Joseph Peter Spang III. A note in the book states that the book passed to Jonathan’s half-brother, Flavel, and eventually to William Goldthwait before coming on the rare books market.