The generosity of an anonymous donor has brought the extraordinary gift to the Henry N. Flynt Library of a large and varied group of important rare books. Among them is one of the masterpieces of early European printing: the Liber Chronicarum, or the Nuremberg Chronicle, published in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1493, less than 50 years after the printing of the landmark Gutenberg Bible.

This magisterial volume constitutes a significant addition to the library’s rare book collection: a large folio of over 600 pages, the text printed in formal gothic type, with over 1800 illustrations printed from 652 woodblocks, artfully arranged on every page to complement the letterpress. All that is held together by a stout 15th- or 16th-century blind-stamped calfskin binding, protected at the corners and center by metal bosses, possibly of contemporary German manufacture. Overall, it is an imposing yet beautiful production, universally considered by graphic arts historians to be one of the greatest monuments of book design and printing.

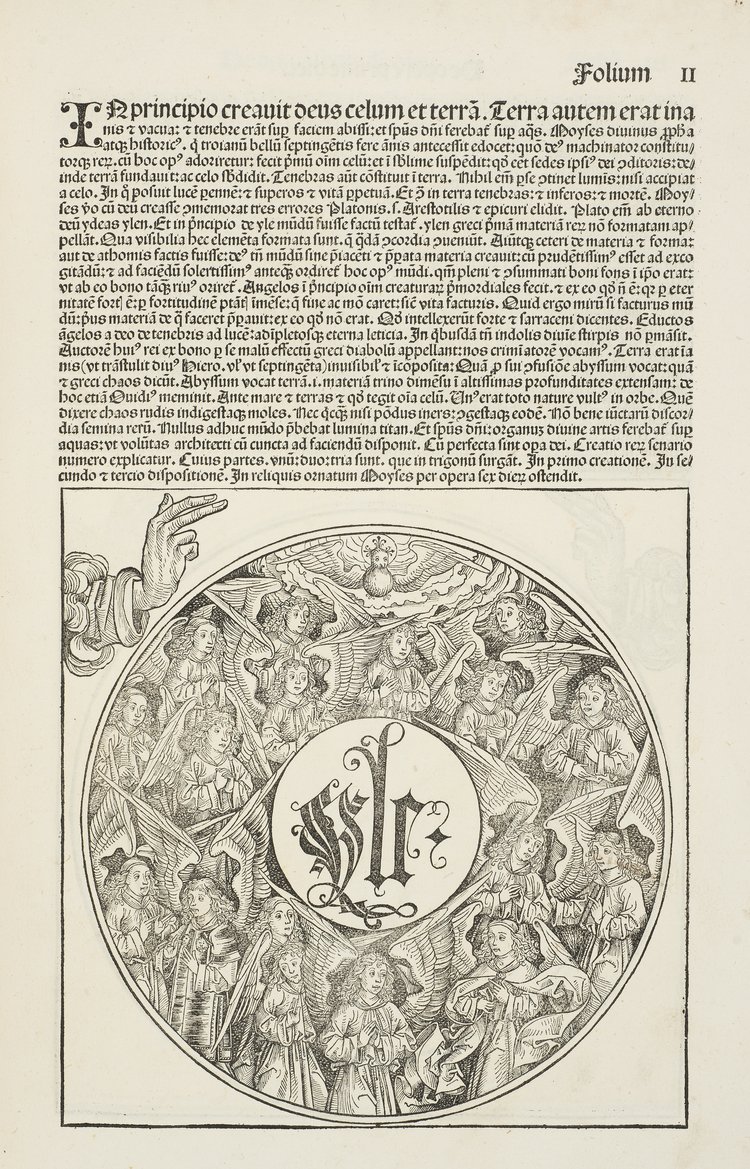

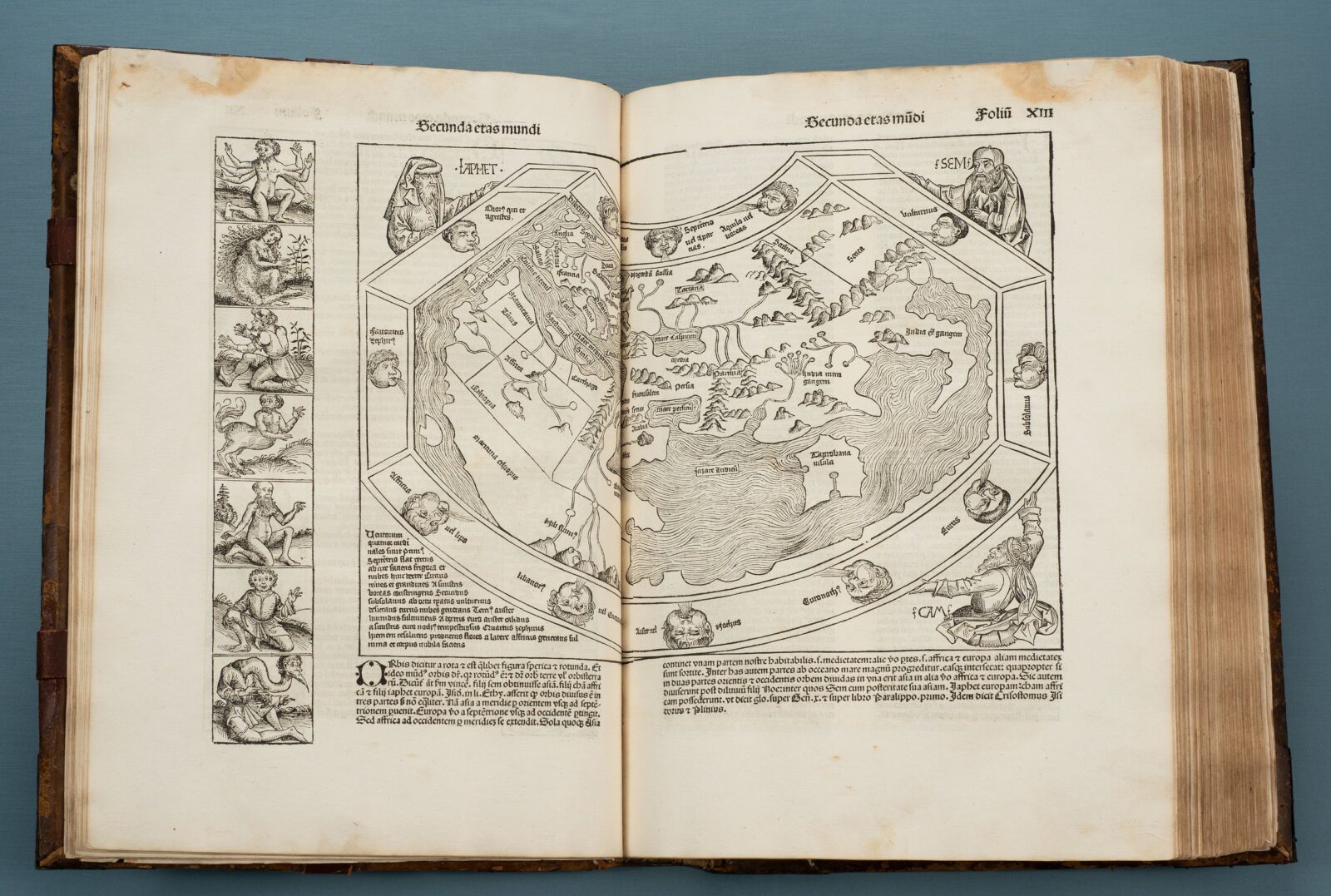

The Nuremberg Chronicle is perhaps the most important example of a particular genre of world history or Weltchronik, that presents all of human history—past, present, and future—within a Western, Christian framework. Thus, it opens with the Biblical account of the creation— In principio creavit Deus caelum et terram (In the beginning God created heaven and earth)—and ends with a description of the Second Coming of Christ and the Last Judgement. In between it recounts not only sacred history, but all manner of secular events and people as well, from the ancient Greeks to contemporary rulers and their exploits, from the rise and fall of great empires to strange portents in the sky and monstrous births, from noble and learned men and women of all ages to the bizarre creatures who inhabit the unexplored margins of the known world. It is an exuberant mélange of religion, classical studies, and the early modern science.

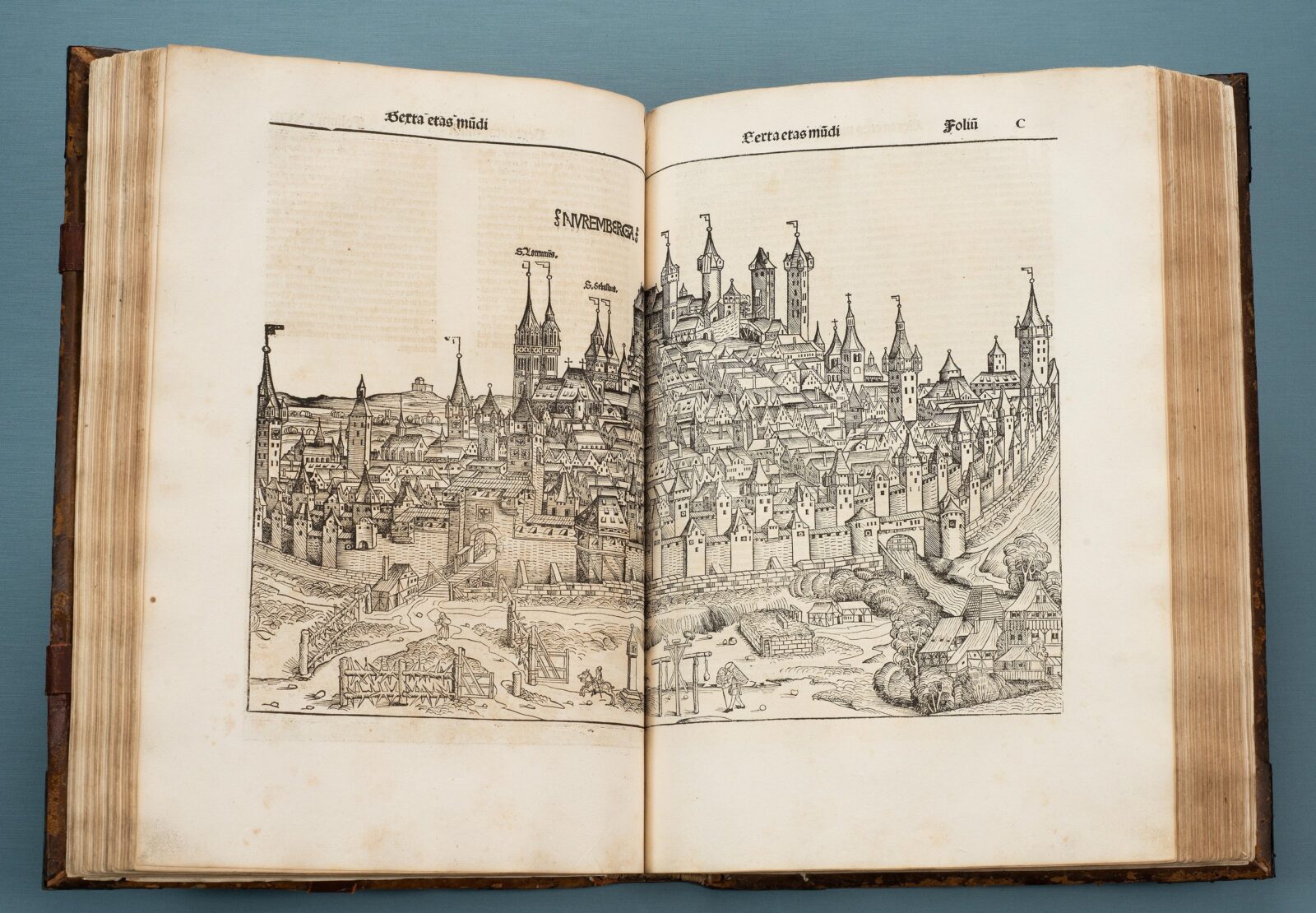

All this history, sacred and profane, is illustrated by a remarkable series of expressive images of famous personages (all of whom are idealized), places (mostly European city views drawn from life), and happenings. Many of the woodblocks are pressed into service more than once: the view of Naples, for example, is also used for Mantua, Perugia, and Siena, and the “portrait” of St. Barbara, with her book and palm frond, also serves for St. Concordia, St. Perpetua, and St. Paula Romana. How many readers would notice the repetition, or care about it, if they did? Such was the power and authority of printing in this period that—for whatever reason—anomalies like this didn’t seem to matter so much. In addition, the illustration program also includes two maps, which are among the earliest to appear in a printed book: a spectacular double-page world map on the Ptolemaic projection and an important “modern” map of northern Europe.

Like the building of a medieval cathedral, this complex publication project involved many of Nuremberg’s skilled artisans and businessmen: the author, the publisher, the dozens of printers and binders, the colorists, the artists who drew the numerous illustrations and the wood engravers who cut the woodblocks for printing them, as well as the bankers who financed it. Hartmann Schedel, the author, was a historian and physician who had studied at the famous medical school in Padua in the 1460s, one of the most important early conduits of Italian Renaissance humanism to the lands north of the Alps. Schedel’s neighbor and friend was Michael Wolgemuth who, along with his stepson Wilhelm Pleydenwurff, operated one of the city’s most important craft workshops, producing woodcuts, altarpieces, and sculptures. He was commissioned with the formidable task of cutting the 652 woodblocks for the illustrations. The young Albrecht Dürer, who lived three houses down from Wolgemuth’s shop and who would later become a central figure in Northern Renaissance art, was an apprentice there in the late 1480s and may have contributed some of the preliminary drawings for the blocks. And Anton Koberger, Germany’s greatest merchant/printer of the period, also lived and worked nearby. In a long and successful career between 1470 and 1500, Koberger published around 250 works in a large shop staffed by 100 workers on two dozen presses, each capable of printing 1000 sheets every day. The Nuremberg Chronicle was his greatest production.

All of this artisanal skill, business acumen, muscle power, and money was brought to bear on this great project, one of the last expressions of medieval, or pre-modern, European graphic arts. But more than that it was, as we can clearly see from our 21st-century vantage point, a book between two worlds: on the one hand it summed up the medieval, or scholastic, mindset that was dependent on the pronouncements of authority, both ecclesiastical and classical. And on the other, we get the glimpses of something new: the enquiring scientific mind that looks unswervingly at the physical world–rather than piously heavenward–and observes and records it. The Nuremberg Chronicle points to discovery; indeed, it was even issued with a number of blank pages bound in so that readers could record the events of their own lifetimes. The blank leaves are present in our copy, but they are still blank: no early owner recorded the glorious deeds or cataclysmic events of his or her lifetime!

The printing of the Latin edition of about 1500 copies began in the spring of 1493 and was finished in early June. That same year a German translation was made and a German edition of around 1000 copies printed. You could buy a copy either bound or unbound, colored by hand or uncolored; in any case it was a very expensive proposition and beyond the reach of most readers. Copies were acquired for institutional libraries–monasteries, universities, cathedrals—or by aristocrats, wealthy churchmen, or patrons of the arts. Ownership by this privileged clientele meant there is an unusually high survival rate of copies of the Chronicle. In fact, a census of copies of the Nuremberg Chronicle in America, published in 1964, lists nearly 200 copies in institutional collections; among the earliest to arrive in this country was a copy once owned by Christopher Daniel Ebeling and given by him to the American Antiquarian Society in 1816. Nowadays, only a very few copies make it on to the rare book market each year, and they command rather breathtaking prices when they do.

Which is why Historic Deerfield is very fortunate to have been gifted this splendid copy. It is a keystone book, a monument, in the history of graphic arts. It embodies the highest level of craft—typography, papermaking, bookbinding, book illustration, design—in the Renaissance and early modern periods. And it now serves as the starting point or touchstone for Historic Deerfield’s newly-announced revival of the John Wilson Printshop and the related exploration of book culture in colonial New England that will commence later this spring.

Martin Antonetti is Printer in Residence at Historic Deerfield, where he interprets early 19th century American book culture at the Wilson Printing Office.